I love what I have been seeing on my Facebook timeline this week—students from colleges nationwide are virtually standing in solidarity for the black students at Mizzou, and it's inspiring to watch this support go from being a historic event in Missouri to a trending discussion on the Internet. I am so proud of the students at Mizzou for being able to set aside their differences and unite for the greater good. College students today seem to be going to greater extremes to implement serious change on their campuses, and while I applaud their efforts, I am also alarmed. It worries me that Mizzou's administration might not have cooperated with the demands at hand had members of the high-profile, instantly accessible football team not aligned themselves in solidarity, or had the graduate student not undergone a hunger strike. Furthermore, it makes me wonder what it really takes to convince college administrations to pay attention and act accordingly in the face of racially charged issues.

When I read the tweets that people have been sharing about their experiences as black students at predominantly white institutions (PWI), I was reminded of the struggles I dealt with at my college. There's another side to the reactions of what happened at Mizzou that everyone is blatantly ignoring—why won’t students stand in solidarity at their own campuses, and where are they when these issues are going down in their own backyards? Why is it only the high-profile cases that move us into action?

I admit that I have not always been an active member of the black community. I grew up in the suburbs of New Jersey in a town that I believed to be diverse, but I have always attended predominantly white schools. My inner circle of friends has consisted of people of many colors, but I have never been a part of my own "unfriendly black hottie" crew. There have been times in my childhood where I was mildly exposed to racism, like when my classmates called me an "Oreo," or when my friends said that I was "so white," but I always shrugged it off because it wasn't a big deal to me at the time. I was usually the only black student in my classes, but I distinctly remember this one time in high school where I registered for African-American History, and my teacher was white. I was a little shocked, but I can’t explain why it didn’t bother me then. I guess I just didn’t care.

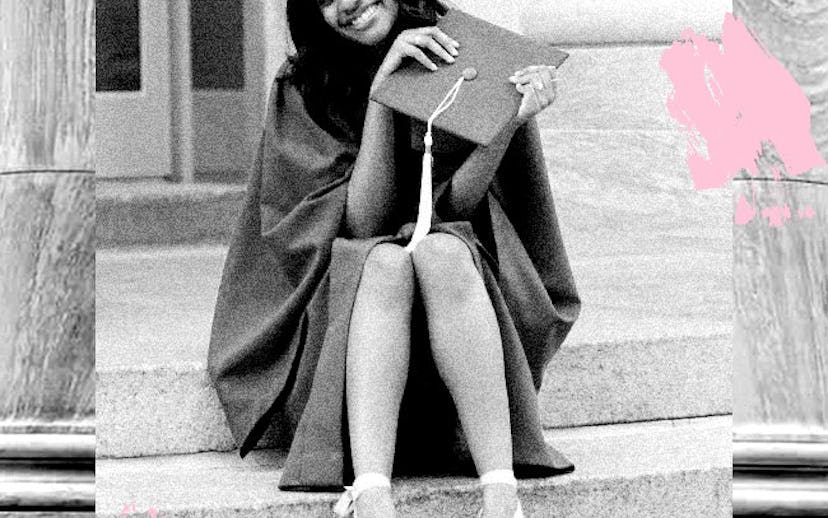

A few months ago, I graduated from American University in Washington, D.C. The college is located in Tenleytown, which is a suburban residential area. For the most part, I had a positive experience at AU. It was my first choice, and I applied early decision to the university so I could pursue a B.A. in Journalism. From an academic standpoint, AU is a great place to be. Socially speaking, there is so much room for improvement, though. Unfortunately, during my last year at the university, my race became the target of highly offensive messages on Yik Yak, an app that allows people to post anonymously within a certain radius. The comments would be anything from people saying that they hated black people and that we were all thugs that didn’t deserve to be here to agreeing that Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin deserved their untimely deaths. What was Yik Yak used for normally? Racial tension has been escalating at colleges everywhere, but I never expected to see it happen at AU.

Sure, there were always the little things that nobody liked to talk about—I remember rushing for social sororities and coming out of it with a new perspective on how minorities are all treated like tokens in a game. I didn't pledge to Greek life, because by the end of the process, I wasn’t sure if the women that had been talking at me wanted me in their sororities because they actually liked me as a human being or because they needed to bump up their diversity count. (At the end of the day, it’s always about the numbers.) There will always be a professor who expects you to speak on behalf of your entire race because you are the only person of your ethnicity in the room when you never asked to be burdened with the pressure to be the designated representative. These are common pieces of the black experience for those of us that attend PWIs.

From the beginning of my first semester, I was involved in an assortment of student organizations from the student-run newspaper and student government to the student-run radio station and a student ambassador for the School of Communication. I have never considered myself to be an activist as I have always preferred to express my opinions through the written word, but after ranting about the messages on Facebook, I finally decided to write an op-ed about the situation for my student newspaper, The Eagle. The feedback I received for my article was mostly positive, but there were a few concerning comments that affirmed that this was not enough and I needed to do more. I realized that it was time for me to physically get involved because no matter how I looked at it, this was about more than me as an individual—it was about every black person in America.

The black community on my campus pushed for our administration to do something about the racial tension and was met with nothing but letters from the university President about how this behavior would not be tolerated. Dissatisfied with the response, we protested and marched on the quad—a normal activity that students from my school tend to do. Instead of being met with support by our peers, we were criticized. Students posted statuses about how our chanting was disrupting them from studying because this happened to occur during finals. It was insulting how someone had the audacity to argue that a protest was disrupting their life for one day when bullets fired by police officers across the country were disrupting the lives of unarmed black men every day. The backlash was so bad that it got to a point where people were calling our demonstrations a "minstrel show" on Yik Yak. (I want to point out that my student body constantly rallies in support for anything that has to do with the environment, but as soon as the discussion turns to the human lives that occupy that space, allies are silent and nowhere to be found.) Fast-forward a year later, and the messages are still circulating throughout AU's campus—the only difference this time is that the Washington Post took notice.

Black voices are ready to be heard, and it’s time for the outside world to start listening. While allies are always encouraged, there’s more to being politically aware than posting a status and we can't always rely on a Division I sports team to make people care about fundamental rights that we are all entitled to. Students have the right to feel safe on their campuses and should never be scared to come to class because of threats that trolls post anonymously online. Colleges are supposed to be learning environments for everyone—not war zones—and administrations should be protecting them. As a college graduate with a degree, the most important thing I took away from my undergrad experience is that while it is important to know what is going on in other places, those that aren't willing to acknowledge what is happening right in front of them haven't learned anything at all.