Get To Know “An Incomplete History Of Protest” At The Whitney

We spoke to curator David Breslin about the exhibition

How many protests have occurred in America? How many in 2017 alone? The numbers aren’t really important, but the act of protest—and the act of documenting them—is. This year, exhibitions such as “We Wanted A Revolution” at the Brooklyn Museum and “We Need To Talk…” at the Petzel Gallery in Manhattan were indicators that politics and protest are both pressing themes that art institutions have taken an interested in exploring.

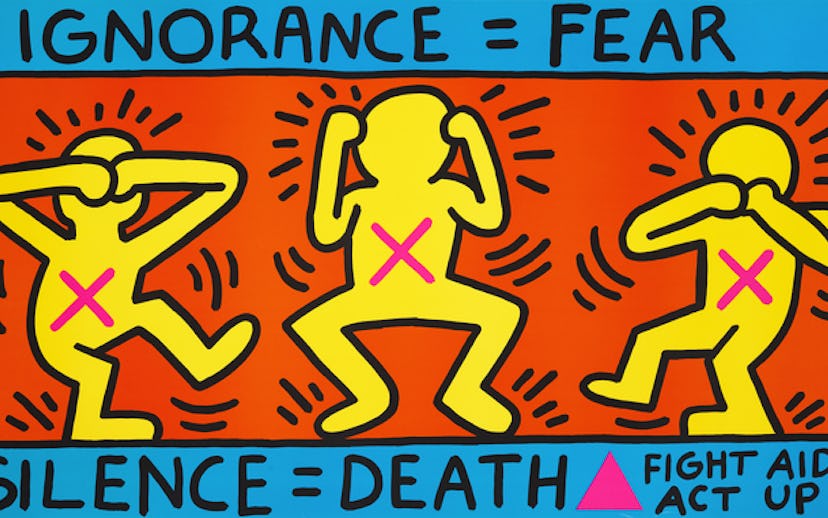

Tomorrow, the Whitney Museum of American Art will add to this conversation with the debut of “An Incomplete History of Protest.” The exhibition features selections from the museum’s collection, ranging from 1940 to the present, and is broken into categories, including Resistance and Refusal, Spaces and Predicaments, Stop the War, Mourning and Militancy, Abuse of Power, and more. The show will showcase works by artists such as Larry Clark, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Guerrilla Girls, and Toyo Miyatake.

Ahead of the opening, we spoke to curator David Breslin about the organization of the show, the many forms of “protest” art, and how there is still much more work to do.

In your own words, what is this show about?

This was a way to really show that history of collecting [protest] work, and [the museum] supporting that kind of work. But obviously, given the fact that the country is at a particular point in time where we see protests happening in various ways, we see artists thinking through what protests can mean in their own practices. We thought it would be really compelling and important to trace a history of the different ways artists have approached this idea.

Scott Rothkopf [the Deputy Director for Programs and Chief Curator at the museum] has called the Whitney “a forum for the most urgent art and ideas of the day.” How does that speak to this exhibition?

One of the things that we wanted to do was look directly at Whitney's own history to be self-reflective in this moment. So we have a gallery that really looks at moments in the ‘60s and ‘70s when artists were really looking closely at the museum to see how it also mirrored a larger culture. And the Whitney, in particular, is a place that people come to expect different ideas of what America could mean, and how that institution was putting different ideas forward about our relationship to war, or the inclusion of women and black artists, or access to the museum. There are still issues that we're dealing with today, and I think what's really profound is that there are issues that our country is living with. These are things that artists have been dealing with and hopefully, there's a through-line in the show that indicates that artists are still working hard—if not to remedy these urgent problems—to look very closely at them and see what's happening in the culture that makes these issues.

How did you define “protest” when conceptualizing this exhibition?

It's a great question that I thought about with my colleagues (assistant curators Ru Hockley and Jenny Goldstein). In some ways, what was really important to that, was we brought different ideas of what protest means to the table. We really pushed each other to think, and we needed to be more expansive in some ways. Something like Martha Rosler's video, Semiotics of the Kitchen, might not look like a boots on the ground, fists in the air type of protest. But when you're thinking about how different systems or ideas—whether it's domesticity, or what femininity means—if you're working against these social issues, we [considered] that type of work as a form of protest, as well.

When I spoke to the curators of the Whitney Biennial, they mentioned that, although they didn’t intend it, there was a political undertone that was present throughout the show. What are some of the challenges in curating an exhibition that is overtly political, that tackles this theme head-on?

I think, in some ways, we had the benefit of having the [museum’s] collection as a limit. We couldn't do everything, and you can't address every issue that is extremely important and relevant in the current moment. At the same time, since the collection is a limit, it's also really generative. You tell new stories by putting different objects together in new ways, and they kind of rub against each other. I think one of the challenges was to make sure that each gallery really had a really precise thesis, so that, when you're putting works together, it doesn't look like politics are all the same. There will be works in the show—like these great protest posters around the Vietnam War—that, in some ways, look like protests. But there are also works in the show that use abstraction to show that protest can happen in many different ways and that artists really think thoughtfully around what the histories of different forms and visuals are that have addressed protests in the past. And that this is something that is modifying and developing as time goes on.

This exhibition will occupy the museum’s sixth-floor gallery. How will it be organized?

We've tried to marry it so that it's chronological so that people can get a sense of the way that different artists approach different ideas of particular moments in time. And then, each chronological section has its theme. We wanted each section of the gallery to have its own tone. For example, when you walk into the first gallery, it deals with issues of racism during the Civil Rights Era. But then you go into the archive section, the ‘60s and ‘70s, it becomes more like a reading room. We wanted to make sure that these different particular periods were punctuated by a mood in the gallery that made people feel like, as they were traversing the exhibition, you were in a really particular place at each time.

What do you hope viewers will take away from this show?

I hope people will look at the collection as one that's both really alive and sensitive to this issue. But I also hope people think there's more work to be done. Both in terms of how we improve culture, but also in how we really make different and meaningful contributions through art, through what museums do, to kind of work with these ideas. Because I think that's part of what we're looking to do with the show: say that this work isn't done, it's ongoing. It's one of the reasons why we wanted to have "Incomplete" in the title of the show. Not just to signify that the work of protest is incomplete, but the work of the museum in trying to work closely with artists, to see how we can be in step with each other. And thinking about what different futures could be is something that we're all hopefully working toward.

Scroll through the gallery below to see more works from this show. For more information about this exhibition, click here.