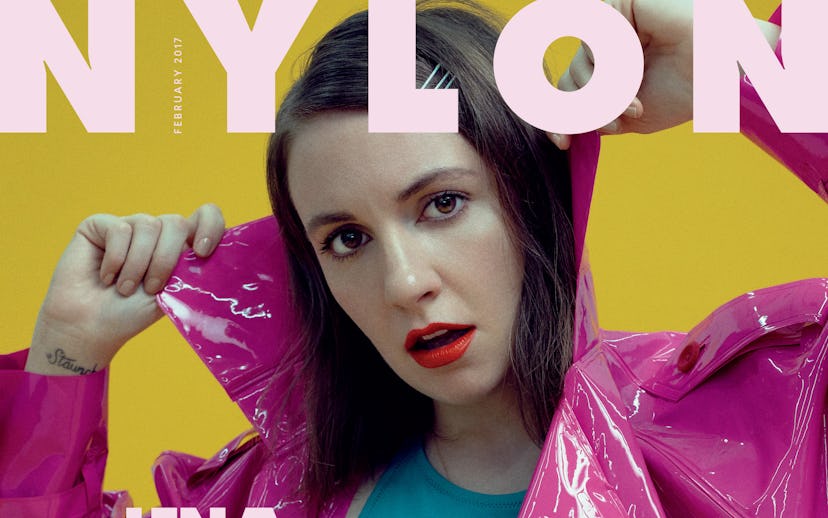

Lena Dunham Is Our February Cover Star

Dunham talks the end of ‘Girls,’ our new president, and being a workaholic

The following feature appears in the February 2017 issue of NYLON.

Like many successful, so-called nasty women, Lena Dunham is a masterful practitioner of the sugarcoated business voice. You know the one; Melanie Griffith cooed it in Working Girl. Taylor Swift could offer an MBA in it. Game of Thrones’ Margaery Tyrell wrapped boy-kings around her pinkie with it. If you wield it incorrectly, though, beware: Hillary Clinton, Dunham’s political girl-crush, never powdered enough sugar on those boss pipes during the election, according to the pundits. And, well, we all know how that went.

Dunham, 30, identified with Clinton, whom she actively campaigned for alongside friends America Ferrera and Amber Tamblyn, because the demands to be a different kind of woman have burned her, too. More aggressive, more gentle, more clothed, more invisible, more whatever, it’s always changing. But after six seasons of creating, writing, directing, producing, and acting in her HBO series, Girls, which premieres its final season on February 12, Dunham has finally learned how to be her own kind of bohemian boss. She’s learned to apologize when she makes mistakes, but never to apologize for living in plain sight. And living in plain sight means asking for what you want—but in the voice, always the voice.

On a Sunday morning at Soho House, the West Hollywood outpost of the posh members-only club for creatives, Dunham and I search for a table in the buzzing dining room. We’ve already rejected the garden area, which threatened to erupt into live jazz at any minute. We could wait for a hostess, but instead Dunham sidles right up to the bar in her tan Ugg boots, heather gray sweats, and Fair Isle cardigan. “Hiiiiii,” she says in a bright, cheery tone, followed by a honeyed but firm request to be seated, her unwavering eye contact reaching state diplomacy levels. We’re led to a lovely perch by the windows. But when the waiter doesn’t visit fast enough, she’s back up to the bar. “Hiiiiii,” she says, before sweetly demanding that he come by quick.

To me, she says, “I’ve always done this. I learned it from my Jewish mother. I didn’t start doing this when I got famous or anything.”

Dunham tosses this off nonchalantly, but there’s a perverse thrill to it, this mentioning of her celebrity. She was perfectly polite to everyone, but realizes how close she veered to the diva celebrity cliché (and being a diva to service-industry people is the rankest of diva sins). Instead of letting it quietly gain traction, she calls it out. This is peak Dunham. Naming the chafing spots that happen in everyday interactions is her favorite sport. The trivial, the gauche, the downright forbidden—she loves all of her awkward children. Part of the game is that she recognizes you’ve noticed it, too, and she’s already one step ahead of you by having the audacity to name it.

In person, the hyper-articulate, hyper-self-aware Dunham is a marvel to behold, if a little unnerving. She’s so observant—fluidly tracking every single time I scribble a note, eye contact like a retinal scan—that sitting across from her gives the sensation of being read by a super-high-performing care robot. She’s not cold or forced—quite the opposite, in fact. Her bare face with just a hint of coral lipstick lights up when she’s excited, which is often. She’s warm and spontaneous, funny and disarming. It’s just that she speaks and listens (every single friend of Dunham’s I talk with praises her full-body listening skills) with such tangible emotional access and presence, it’s a little uncanny. Underneath the lighthearted self-deprecation and quips about how both she and her dog Susan have endometriosis is a laser-focused mind that barely misses a thing.

She admits, though, that there are gaps in her self-knowledge: “I’m realizing more and more as I get older that I’m actually way less self-aware than I thought,” she says, noting that she countered the first pings of public critique with shielding thoughts like, “‘Oh, I’ve been in therapy since I was seven. There’s nothing you could say about me that other people wouldn’t know.’ But the older I get, the more I’m like, ‘I don’t fucking know what anybody is seeing when they look at me,’ and the coolest thing is it’s not my problem.” Her hazel eyes open wide. “That’s an interesting thing. It kind of doesn’t matter. I used to think the worst thing in the world could be for someone to have a thought about you that you didn’t have yourself. Now I’m like, ‘Have at it, guys!’”

Have at it they do. Since its premiere in 2012, legions of futon critics have claimed they could make Girls better than Dunham. And truth be told, certain aspects of the show don’t feel right to her anymore either. “I wouldn’t do another show that starred four white girls,” Dunham, who plays Hannah Horvath, acknowledges. “That being said, when I wrote the pilot I was 23. Each character was an extension of me. I thought I was doing the right thing. I was not trying to write the experience of somebody I didn’t know, and not trying to stick a black girl in without understanding the nuance of what her experience of hipster Brooklyn was.”

She wasn’t alone in her self-doubt. Jemima Kirke, Dunham’s childhood friend who plays Jessa, the long-haired wild child with a secret grounded core, hardly accepted herself as an actor on a prestige network. “I didn’t think I had earned that show,” she says. “It was like, ‘You didn’t even take a class.’ I was embarrassed to say I liked acting.”

But when Jessa got her most meaningful story line—dating Adam, Hannah’s mercurial ex played by the series’ breakout actor, Adam Driver, in season five—Kirke sunk deeper into her character, thrilled to be given more responsibility by Dunham. “In the beginning,” Kirke says, “she was holding on really tight. She was a machine of creativity, of putting out this product. She’s dropped that significantly and the creativity level has gone up.”

In a season where many characters wrestled with their boldest story lines yet—Marnie (Allison Williams) got married, for instance, in a feast of twee-folk narcissism—none inspired debate in the writers’ room quite like Jessa and Adam’s budding affair. “That’s what takes someone from being kind of a shitty friend to being an actually shitty friend, but at the same time, it’s one of the ways you meet people,” Dunham says. Her beloved parents, the artists Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham, met this way. “I am the product of a much-discussed downtown SoHo romance,” she merrily dishes, “that put a few people in a really bad mood.”

Kirke sees her character’s development as a sign of Dunham’s growth, creatively and beyond. “Lena’s becoming more free,” she says. “She wants people to understand her, but she’s also trying not to apologize so much. I don’t know why Lena Dunham, more than anyone else, is asked to fucking apologize so much.”

For all of Dunham’s emotional intelligence, she has her blind spots. That desire to call out the awkward moments sometimes backfires, like when she joked about the NFL player Odell Beckham Jr. ignoring her at the Met Ball because she wasn’t attractive enough (a joke that unfortunately involved projecting misogynistic thoughts onto a black man she didn’t know).

Her good friend, writer Ashley Ford, wishes more people would recognize Dunham’s efforts to broaden her perspective. “I’ve never seen her not take the opportunity to learn how her words and actions might affect other people. That’s what frustrates me about reactions to her.… She’s perceived to be this super-evil pinnacle of white feminism, but they haven’t even investigated those feelings,” Ford says of Dunham’s critics. “A lot of them decided a long time ago that they don’t like her. She can’t live by those opinions.”

Dunham can, however, respond to the valid concerns that she hasn’t done enough to depict life outside the white hipster bubble. Quietly, outside of Girls, she’s been building a media fempire that constitutes what Ford describes as a new platform “to support women’s voices that need to be heard the most.” Lenny Letter, the media brand she created with longtime Girls showrunner Jenni Konner, and Women of the Hour, her podcast now in its second season, are both showcases for eclectic stories, including Ford’s own gripping experience with her father, who was incarcerated 30 years on rape charges. A recent WoTH episode, “Faith & Spirituality,” featured a Muslim woman sharing dating tips, and a hilarious tale of a lapsed Mormon in flagrante with a former Orthodox Jew. In both forums, Dunham leaves her stamp, with her nurturing interviewing style and wryly vulnerable stories, but she isn’t the star by any means.

Konner says that Dunham came “pretty fully formed as an artist,” but it’s been her comfort level with public life that’s grown in the past couple of years. “She’s honest and straightforward, and it comes with a price. I see it chip away at her, but ultimately, it’s more important for her to be a Hillary supporter and a supporter of reproductive rights. It’s more important to be out there,” she says.

Due to her campaigning for Clinton, but also because she’s been targeted as an outspoken feminist for years, Dunham has been harassed by the alt-right brigade. After Trump won the election, her Instagram account, where she captures life with her three fur babies and boyfriend Jack Antonoff, was besieged with threats. To a certain degree, she understands why she’s a target: “So much of what we’re dealing with in America isn’t just misogyny, isn’t just racism, but is also this unspoken constant tug between people living on different sides of the class divide,” she says. “You come in and you’re like, ‘I went to Oberlin. My godparents are both art critics. I was raised at a women’s action coalition meeting,’ and that’s repugnant to them on a thousand levels. There’s a sense of snobbery or intellectualism that feels like it’s the enemy of patriotism and also the enemy of the working class, which is by no means where I ever wanted to position myself.”

Dunham is clear that she doesn’t condone any threats or violence, but she’s always open to respectful conversation. Her younger sibling, Grace, a gender-nonconforming activist who has been dragged into the alt-right maelstrom before, is in a constant debate with Lena. Is it better to be radical and reach fewer people, or soften the message and reach more? “Lena is an amazing listener, and she’s not stubborn,” says Grace. “But she’ll push your thinking—she’s pushed me to really consider the goals of my activism. We go toe to toe; it’s really rigorous.”

“Grace is my fucking boss spirit guide on this stuff,” Dunham says. “She’s definitely the best member of our family, and I don’t think anyone would refute that.” The two text daily, Facetime every few days, and spent this past Thanksgiving together serving food to trans teens at a community center. Grace is six years younger but very protective of her older sibling. “I wish she’d move to British Columbia, throw all her tech in the ocean, get a garden going, and write a novel,” Grace says. “She’s been prolific for so long. She will never stop making things, that’s one thing I know. You could tie her hands behind her back, and she’d still find a way to write.”

The young woman’s curse, the need to be liked by everyone, has been one of Dunham’s toughest lessons professionally: “Sometimes being a creator, and especially being a female creator, is an exercise in shutting people’s voices out, because there are so many who think they understand better than you how to do your job,” she says.

Threats be damned, Dunham won’t be quieting her voice anytime soon. For the final season of Girls, “we wrote in a climate where we were thinking a lot about this election, and the election was heating up as we shot the show, and that energy for sure made its way into how we tackled topics. I don’t mean to be demurring, but there are some big female issues, more than maybe ever before,” she says.

While Dunham shares a home with Antonoff, both in New York and Los Angeles, the die-hard workaholic says she would hardly see her boyfriend if they didn’t intertwine their frenetic work lives. (She’s directed a few of his music videos, and he contributed two songs to the final season of Girls.) “I have no social life, I have a tiny personal life, and I work myself to the point of illness three times a month,” she says. In 2016, she had three surgeries related to her severe endometriosis. Her friends and family wonder if her pace is sustainable.

That question will be carried over to the conclusion of Girls. “This is for sure the season where people are like, ‘It’s now or never. Am I going to perish in the worst apartment in Bushwick, or am I going to figure out a way to actually live where I’m not scared every day?’” she says. “It’s also a lot about examining these friendships, which we’ve looked at over five seasons, and asking, ‘Are these sustainable in any way? Why are we even doing this? And are these friendships even the healthiest thing for us, or are we holding on to hold on?’”

For now, Dunham is taking what she calls a break, which really means the following roster of activities: publishing her book of short stories about the complexities of female-male relationships, Best and Always; growing Lenny Letter’s recently launched book imprint and collaborating with HBO Go on a series of Lenny Letter short films; and going to London to research a film and theater project. Feel like a sloth yet?

When Girls exits for good, “I’m probably going to have a nervous crying breakdown,” she says. As we speak, she only has one more episode to edit. “I had a psychotic moment where I was like, ‘I’m going to become a wildlife rehabilitator and a crystal expert.’ My boyfriend was like, ‘No, you’re not.’ I’m like, ‘I’m going to rehabilitate squirrels and owls. And I’m going to educate myself so that I can do crystal healings.’ He was like, ’Good luck with that.’”

The truth is, as much as Dunham loves the woo-woo side of life, she’s on a bigger mission. “It’s going to be interesting promoting this show right after Trump is inaugurated. The final season definitely tackles some topics that are complicated and wouldn’t be beloved by the incoming administration. Hopefully it’ll bring up important conversations, and not just become the worst Twitter abuse storm in history—or it will,” she says, but she’s prepared to weather it. “The confluence, for me, of the show ending and this new era beginning in which I know that we as public women are going to have to fight harder than we ever have before, is a really interesting, complicated moment.”

No matter the reaction, Dunham will protect her creation—a TV document of her growing up before our eyes. “I know I’m never going to have another work experience like this,” she says. “Eight years of working on a project; it’s this living, breathing organism, but it’s also the luckiest thing.”

NYLON’s February 2017 issue hits newsstands January 17. Buy it now or subscribe.

Photo assistants: Leon Singleton and Sean Costello. Stylist’s assistants: Nicola Rowlands and Hunter Woodruff. Hair: Marcus Francis at Starworks Artists. Makeup: Fabiola at Tracey Mattingly using Sephora Collection Colorful. Manicurist: Kait Mosh at Cloutier Remix. Set design: Jamie Dean at Walter Schupfer Management for Jamie Dean Studio.