Drinking Seltzer And Getting Life Advice From Marilyn Minter

“Be obsessive and slightly delusional”

"Why does everybody think that women are debasing themselves when we expose the conditions of our own debasement? Why do women always have to come clean?" — I Love Dick, Chris Kraus

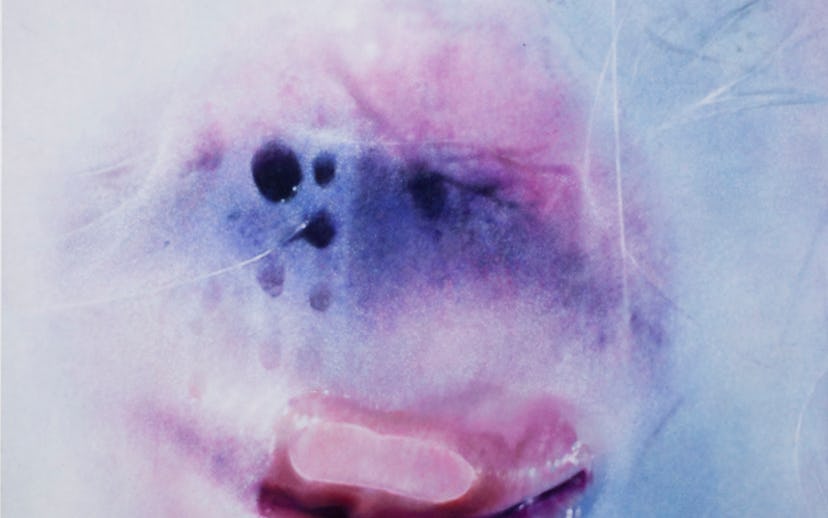

I can never remember if white is supposed to be the color of life or death, but standing inside Marilyn Minter's cavernous bright white studio, walls close to bare due to the fact that much of Minter's recent work is on exhibit now at Salon 94 and much of Minter's entire oeuvre is included in her major career retrospective, which opens today at the Brooklyn Museum, feels not unlike being in a womb. Because despite all the white, there's nothing sterile about it. The space has a palpable tactility, the intimacy of a bruise. This is, in part, thanks to the lurid pink and purple slashes of paint on those white walls, the by-products of her recent paintings, enormous enamel-on-metal works which feature steamy, sexy, dripping images of women, often behind glass—in effect trapped, in reality free. There's a sloppiness, a messiness thanks to all that conjured humidity, but the closer you get the easier it is to notice the precision of even the smeariest blurs. There's nothing not deliberate.

This, at least, is what I was thinking as I waited in Minter's studio, sipping on the seltzer her assistant Johan (who's been working with Minter since he was a student of hers at the School of Visual Arts in 1992) had directed me toward. Around me, several other of Minter's assistants worked on the scant few paintings hung up on the wall, using their fists to pound colors—baby blues, delicate violets, decidedly non-Glossier pinks—into their place. The scene was serene; the only sound was the art being made. That all changed when Minter entered; it didn't become chaotic at all, but the energy shifted, a perceptible hum was now in the air. This partly, of course, had to do with the fact that Minter was the reason I was there, was, in reality, the reason that any of us were there, but it was also because Minter is an exceptional host and conversationalist, the kind of person you'd want to sit next to at a dinner table or stand talking to in line for the bathroom at a party; Minter feels like the ultimate girlfriend, exactly to whom you'd text images of your highlighted favorite sentences from I Love Dick or ask to go with you on a visit to Planned Parenthood.

It's funny, then, that at one point during her more than four-decade-long career, Minter was seen as anti-feminist, for the sexually explicit "Porn Grid" paintings she made in the late '80s and early '90s. In retrospect, it seems absurd that Minter was castigated for this type of work; in 2016, it fits seamlessly into our current ideas of feminism and claiming our own sexuality. Minter tells me, "I'm so glad I've lived long enough to have those moments where I'm really communicating, because with that really early work, millennials go, 'Huh? What was the big deal?'"

In fact, the celebration of Minter's work—both past and present—makes a great deal of sense now; the recent cultural embrace of patriarchy-challenging works by everyone from Chris Kraus to Jill Soloway is in keeping with Minter's work, which has been making men uncomfortable for many years. Minter revels in this, and is not only a definite fan of today's youth ("millennials, none of them are for Trump unless they're backward fuckwads") but has also collaborated with perhaps the ur-millennial, Miley Cyrus, in a campaign to support Planned Parenthood. Minter explains that Miley works hard and "tries to do the right thing. She's a sponge trying to learn. She was a huge Bernie supporter, and she went and campaigned for Hillary. She's flexible."

There's not a little of those qualities in Minter herself; an avid user of social media, Minter's inquisitiveness about, well, just about everything is crystal clear. She agrees, "I'm very curious. Someone told me once I'm the most curious person they ever met... but that's what it is, I have this intense curiosity." This quality manifests in her art, from the "Coral Ridge Towers" series (1969), haunting black-and-white images of her mother applying makeup and smoking in bed, the sense of wasting, fading beauty permeating every frame, to her large-scale photo-realistic paintings of dirty, beautiful things like filthy feet tipped in acid green toenail polish, images which tease and toy with their viewers, forcing them to embrace a visual decadence which maybe they've been told and taught to resist.

Resisting Minter's work, though, is denying progress, not only in an artistic sense (seeing the through line of her art in the retrospective is both illuminating and inspiring) but also in a social and progressive one. Minter and I talk about her lack of association with any one idea of what she was supposed to be like or supposed to be doing ("I was never attached to any institutions... I never thought it was realistic") and it's this refusal to limit herself or only look backward which makes everything Minter does—no matter if it's 40 or 20 or 2 years old—still feel relevant. There's something organic about that, something natural and inevitable. This is not to say that Minter hasn't worked incredibly hard to get where she has (she seems easily like one of the busiest people I've ever met), but rather that she's doing exactly what she's supposed to be doing, creating art and challenging perceptions and expanding minds. Plus, Minter's doing it all in a way that's inimitably her own. And as she tells me, "If you have integrity in your work, that shines through. This is my first retrospective, and I'm 68. Yeah, it's my first one, fuck you. I'm not going anywhere."

"Marilyn Minter: Pretty/Dirty" is at the Brooklyn Museum from November 4 to April 2; "Marilyn Minter" is at Salon 94 from October 27 to December 22.