Entertainment

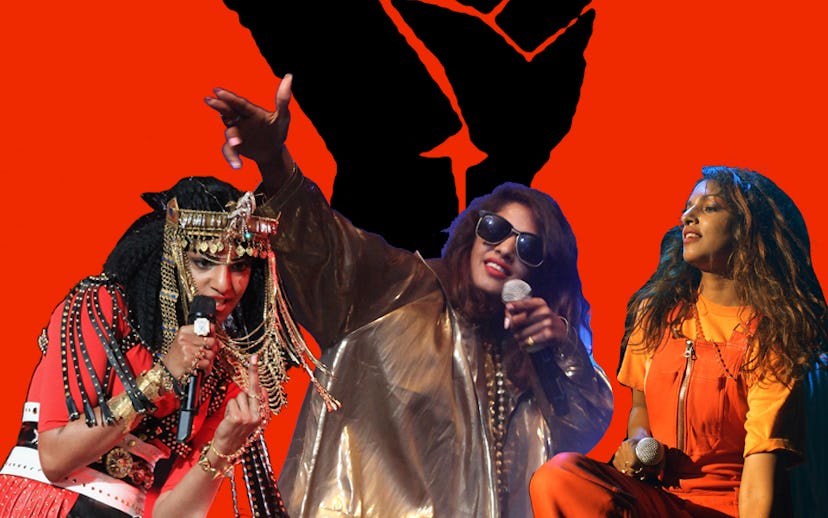

M.I.A. And Asian Solidarity: How To Move Forward

Decoding the musician’s problematic take on racial politics

As a high school freshman, I listened to a lot of Arctic Monkeys, The Wombats, and The Pigeon Detectives. Basically, a lot of white guys with guitars. But when I first heard M.I.A.’s “Paper Planes," I felt like I had opened the door to a new world: a world where I could finally see myself living in as an immigrant and a young Southeast Asian girl.

It was the first step into an era of women musicians of color that I didn’t know I had access to. When this Sri Lankan-British rapper entered my view, I clung to every little bit of representation I could get, just so I could feel validated in a country that didn’t have a place for me. And when she rapped about “Third World democracy,” I also started seeing visions of global solidarity.

That was 2008.

Eight years later, after her comments in an interview on the Black Lives Matter movement, her “Third World democracy” has become very limited, and it’s something I can no longer support. I’m not interested in a solidarity that does not include or even recognize the necessity of black liberation. And neither should other Asian Americans or British Asians.

On April 22, Evening Standard magazine published an interview with M.I.A. There wasn’t talk of new music, but instead, M.I.A. had this to say: “It’s interesting that in America the problem you’re allowed to talk about is Black Lives Matter. It’s not a new thing to me—it’s what Lauryn Hill was saying in the 1990s or Public Enemy in the 1980s. Is Beyoncé or Kendrick Lamar going to say Muslim Lives Matter? Or Syrian Lives Matter? Or this kid in Pakistan matters? That’s a more interesting question. And you cannot ask it on a song that’s on Apple, you cannot ask it on an American TV program, you cannot create that tag on Twitter, Michelle Obama is not going to hump you back.”

She later took to Twitter to clarify her statements:

Nicolas Serhan, a junior at Tufts University who has been involved in the school’s Black Lives Matter movement and Students for Justice in Palestine, identifies as both black and Syrian and sympathized with M.I.A. “They wanted a pulled statement from her,” he said. “What are we ready for? When will we be able to say being anti-Arab is a big issue?” Dira Djaya, a researcher at Tufts University’s Consortium of Studies in Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora, said, “Immediately, I was turned off by it.”

But, on the flip side, she also didn’t think the interviewer should’ve asked M.I.A. those questions. “I think the magazine is to blame because they didn’t give her a chance to explain,” she added. “American media has somewhat depoliticized Black Lives Matter in a way.”

It’s an interesting point. Why would the interviewer ask M.I.A. about Black Lives Matter? What could she possibly say that could help the movement that isn’t already being said by black activists? It’s like expecting a heart surgeon to suddenly speak out on the ills of dentistry."

“Black people shouldn’t be the bulwark for social justice movements. And the way she name-drops random causes does nothing for me," CJ Ghanny, former president of an Amnesty International student group, said.

The reason why Black Lives Matter grew into national—and even international—prominence is because of the tireless work of black activists, specifically the three black women who started the hashtag: Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Cullors. America did not wake up one day and decide that black lives mattered, and many people still do not believe they matter.

This isn’t the first time M.I.A’s musings on race in America have been somewhat confused. In 2013, when NFL sued M.I.A. for a breach of contract for her middle finger fiasco during Madonna’s Super Bowl performance, she made a video statement saying that she found the “young black female” cheerleaders to be much more offensive than her flipping the bird.

“If you look at them, they're all wearing cheerleader outfits, hips thrusted in the air, legs wide open, in this very sexually provocative position,” she says. “So, now, they've scapegoated me into figuring out the goalposts of what is offensive in America. Is my finger offensive, or is the underage black girl with her legs wide open more offensive to the family audience?”

In last year’s interview with Rolling Stone magazine, celebrating the 10-year anniversary of her first album, Arular, she said, “There's a black-and-white divide in America, which is fucking regression. All of this stuff, it's not progression.” She also said, “To me it's all really, really backwards. I just wish that there was another album like [Arular] right now that breaks away all of these boundaries people have put up.”

M.I.A.’s comments about race represent several things. In a society where racial hierarchies exist, placing blackness at the bottom and whiteness at the pinnacle, many Asians in the diaspora, living in places like America and the U.K., still struggle to move the locus of racism beyond the individual.

It’s confusing because it’s not like she doesn’t know about global systems of oppression. She’s outspoken when it comes to sexism, corporate greed, and government corruption. And yet, somehow, knowing these issues has not extended to include structural racism in America.

She focuses on what black musicians can do for her, yet does nothing to call out non-black musicians or celebrities who similarly have not made statements in support of Muslims or refugees.

And there’s a certain brand of anti-blackness Asians wear well: we take from black culture for social capital, but still aspire for a place in whiteness—or, in M.I.A.’s case, an aspiration for some muddled, global browness. “She’s asserting herself, but she’s not self-criticizing,” Djaya pointed out.

And this is something we—the Asian community in America—should do more: reflect on the role white supremacy positions us in. We also need to reexamine our history in radical activism. Learn more about Grace Lee Boggs, Yuri Kochiyama, and the Delano Manongs. Because there have been solidarity movements in the past. And when we relearn our histories and our roles, we can—and should—have more solidarity movements in the future.