Entertainment

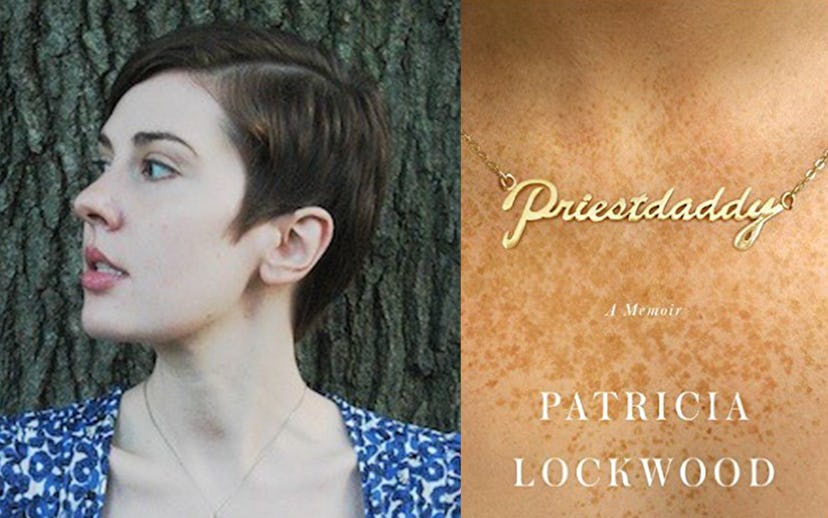

Patricia Lockwood On ‘Priestdaddy,’ Poetry, And Weed Gummies

“The danger when you’re a poet is to not let yourself wank for the entire book”

"I'm sorry for the sort of urinary tinkling happening in the background. I'm sitting near a fountain!"

It made a certain amount of sense that within 15 seconds of talking to Patricia Lockwood, who has been dubbed the "smutty-metaphor queen of Twitter" by no less an institution than the New York Times, our conversation had already taken a turn for the toilet. Luckily, though, the urinary tinkling taking place on Lockwood's end of our phone call was inaudible to me, and I could just concentrate on her melodic voice, which was punctuated by bursts of laughter and at least three over-the-top accents (Italian, Cockney, and what can best be described as "Nintendo Mario") as she emphasized different conversational points.

Lockwood and I were speaking a couple of days after she'd returned to her home in Savannah, Georgia, following a trip to London to promote her new book, Priestdaddy, a memoir centering around the nine-month period in which Lockwood and her husband, Jason, moved into her parents' home in a rectory in Kansas. Lockwood is a poet, whose work has appeared in the New Yorker and the London Review of Books, with two prior books of poetry published, though she is perhaps best known for her piercing poem, "Rape Joke," published in The Awl (and for her absolutely perfect tweet to the Paris Review: "So is Paris any good or not").

Lockwood's writing, both in her poetry and now her memoir (and yes, also, her tweets), has the singular ability to sear you with its often comical, but rarely less than sublime beauty. Her words work as lightning; they devastate with extreme efficiency, you continue to see them in front of you even when you've closed your eyes.

This artistic ability is a powerful thing in poetry, but it can be difficult to extend into prose—especially over the course of 300-plus pages. And yet Lockwood manages not to let the beauty of her writing—or the hilarity of her observations on what is a truly fascinating life, that of growing up one of five children of a Catholic priest (yes, Lockwood's father got a dispensation to be ordained after her was married with kids)—get in the way of the story she has to tell.

And what a story it is! Beyond the inherent oddity of growing up in a variety of rectories and abandoned convents across the Midwest (in her memoir, Lockwood confronts the fact that her family's many moves were often predicated on prior priests' removal due to sexual abuse accusations), there are an abundant of made-for-memoir experiences which Lockwood recounts, and the book is populated with unforgettable people, like her born-contrarian mother and Leonard Woolf-ian husband (Lockwood tells me, "I’m the artistic asshole who can’t cut their own grapefruit or use an elevator properly, and he’s like, 'Tricia, this is how you send an email'"), though it never veers too far into purely funny, since Lockwood's lyrical voice manages to keep things elevated from any kind of base pandering.

Below, I speak with Lockwood about the challenges of writing a memoir, what it means to grow up as an observer, and why she wants to take her mom to Colorado to get stoned.

When you set out to write this memoir, how did you balance writing about such often weighty and serious subjects with a voice that's so ridiculously hilarious?

It’s the thing I knew might be the most difficult, going into it. Because I knew that I had to trick people at the beginning by being like, "This book is going to be funny the whole time," and then cross them halfway through with serious stuff. But it was a question of how do I balance it, and can I have a chapter that’s completely about cum and then, just a couple later, have a chapter that’s totally about death. I knew if someone could do it, it would hopefully be me because I do think I have a certain amount of facility dealing with those really absurd and just very, very serious things. I knew that there was going to be a question of whether I could balance that as much as a reader would want me to. Because, for me, I’m happy to have a book be incongruous and jump from subject to subject, but I knew that if I wanted to reach people from a wider audience, I had to really smooth those things out or weave them together.

I think one of the reasons it works so well, is that the tonal shifts feel much more reflective of the inherent strangeness of life; how even in the darkest of times, the absurdities that hopefully you’ll still be able to laugh at are still there. That's really present in your book, particularly in the way the other people in it conduct themselves.

Yeah, and especially with someone like my mother, she’ll give you some fabulously funny line, and then she’ll tell you someone has cancer. So my experience at home has always been this way, where you had to veer very quickly, just on a dime, from one thing to another.

Has your mother read the book yet?

She has not read it yet, but I’ve read her little sections, and I’ve told her that everyone who’s read it so far considers her to be the star. So I think that that is going a long way toward ameliorating any anxiety she has about the book.

It’s true, she’s exceptional.

She should also be recognizable. Your mom was kind of like that, too, I bet.

Oh, yes. That ability to just, like, drop catastrophic news into regular dinner table conversation is such a mom quality; they can't help themselves.

Oh, totally. And she’s so caffeinated! I feel like a lot of what’s coming from moms is their attempt to juggle all these balls, as moms have to do, and they’re dealing with it by slamming iced tea and coffee throughout the day, so they can really keep up with what’s going on, and at a certain point, they reach this incandescent state of caffeination, and then anything goes.

And then the caffeination gets tempered at a certain point by wine consumption. Moms are, like, the originators of the whole Four Loko phenomenon.

Totally! Exactly. Oh my gosh, we should create a Four Loko for moms. It would be, like, rosé and iced tea.

Just put that in a blender with ice, and that’s the official mom drink.

Yeah, or it could even be in one of those frozen pouches that are so disgusting, and you could freeze them and take them out of your freezer, and put them into a glass. You think that there’s going to be a revival of the Mudslide-type drink? Because it feels like a lot of these ‘90s revival things are going on, and maybe it’s about time for the Mudslide to come back around. I think there might be a market for it.

I used to drink amaretto sours.

That’s my mother’s favorite drink. She loves them. To her, that’s the most alcoholic a drink can be.

It’s Italian, so.

Is it really Italian?

Well, no? But based off of the name, it seems like it’s in the same family as a negroni, but it’s not.

You’re right that maybe I should make my mom a negroni. I think that she would make the most horrible face that you could possibly imagine. She might spit it out! She might lean over and spit it out.

I think you should still try.

I could trick her. Do you think I should… I shouldn’t trick my mom. But, you’re right, it could be worth it.

You shouldn’t trick her. But you should just say, “Would you like a negroni?” Which sounds like… not so scary.

I could just say, [Italian accent] “Would you like a negroni?” Yeah, maybe I can just say it in more of an Italian accent than usual, to make it seem really desirable to her. “A negroni… It’s me, Mario!”

I definitely think this would work.

I’m trying to get her to smoke weed with us, legally, at some point in the future. But to her, she’s like, “That’s so illegal.” And I’m like, “Mom, it’s legal in Colorado.” And she’s like, “It will always be illegal to me and God.” And so she totally refuses, and I’m like, "Mom, if you could just travel out to Colorado with me for a weed vacation and just let me write down everything you say, if you let me record your attempts to call the police on yourself after you’ve had, like, a single hit of anything. Please, Mom. It’s for my career. You support my career, don’t you?" [Laughs]

Has she heard of weed gummies? Because maybe that would be more palatable to her? You know they even have rosé-infused gummies now?

Oh my god.

Which I know because I got some for my mom for Mother’s Day last year. She loves them! It was the greatest thing I’ve ever gotten for her. I feel like maybe you could convince your mom to eat weed gummies.

You’re so right because those are like the gummies she ingests for vitamins. So she would, I think, be more amenable to that.

I’m not saying in a way to trick her or anything like that.

Again, we’re not tricking her, let me very clear: nobody’s tricking parents.

Right, nobody’s tricking parents to do drugs, legally. But if you could make it seem a little bit more usual...

Just having a gummy. [Cockney accent] “Just havin' a gummy.” Yeah, and then I can just record everything. That means that I can’t get high myself. Or I’m going to force Jason to do it, stay sober and just write down everything we do... If they want a sequel, this is the beginning, I think.

I have been a fan of your poetry for a long time, and reading your memoir was just a reminder to me of how much I love when poets expand into long-form prose. Your observations on how the world is so beautifully evocative.

It is true that maybe the danger, when you're a poet, is to not let yourself wank for the entire book in that way. Because, in a certain sense, a poet is ["poet’s" voice]: “Instead of writing about my parents, I will go in the front yard and describe every tree that I can see for a thousand pages.” There’s a certain part of us that’s just like, “Hmm… story, narrative, dramatic tension? We don’t care about that, we just want to describe some fucking trees.” So as I did it, I was like, “Tricia, I know you really want to talk more about the sapphire blue of the water here, but then you also have to dip us back into the stream of real time.”

There are momentous things that happen in your life, whether it’s swallowing 100 Tylenol or going to an anti-abortion march when you're not much more than a toddler; you write around those events in a certain way, not always greeting them head-on but instead approaching them from different and unexpected angles. How did you decide what to include and what not to include?

In my house, I felt like a watcher. And maybe that’s because in my childhood I felt like a watcher. Like maybe real life was happening elsewhere, or maybe other people had the power of explosive action and I did not. So I felt that my role in my house was to sort of stand in the corner and watch things. But that doesn’t mean that everything you observe can go in your memoir, because not all of it has to do with you. Reading the book, you probably also get a sense that there’s a great deal left out as well. Maybe you get the sense of me choosing what thoughts and memories are polished the highest. So you’re looking back at your life and seeing it’s a stream and rocks are rising out of the water, and those are the great happenings. And those are the things that go in your book.

It does seem like you’ve been going through your whole life as an observer. Does that have to do with how young you were when you learned to read?

It’s really funny, I was talking to an interviewer in England, and they were like, “How old were you when you learned to read?” And I was, like, three years old. I was really, really young. I could read instantly. I came out of the womb knowing how to read. Maybe a child who learns to read that young does become more of a watcher, or takes experience in, not passively exactly, but maybe as more of a witness. Maybe you get a sense that life is a story before other people do because you’re seeing it written down in this certain way and shaped for your consumption, so maybe you get the idea that that’s a possible thing to do before other people do.

Were you the kind of kid who used to self-narrate as you went through life?

No! But that is so interesting because occasionally I’ll read a book where someone else does that, and I’ll be like, “Oh, that would be so useful!” The way I did it, things were always flashing on my eyes. It was a very impressionistic, sort of a crazy Joan of Arc-type thing. That’s the sort of person who becomes a poet as opposed to the sort of person who grows up to write short stories or novels or something like that. And I never even kept a normal diary or anything like that, which would have been so useful, but I was always like, "Why would I need to go back and see what I ate for breakfast?" Which I NEVER eat anyway because breakfast is… No. I do not accept the existence of breakfast. [Laughs]

What was it then that made you want to write a memoir?

We were living back with my parents, and my husband had no job, and I was sitting there and looking at all the things that were accessible to me that I could potentially help us out of this situation with. Obviously, you’re not going to make any money with poetry. That’s not a thing that’s happening. My second book sold, for poetry, a large number of copies. But it’s still not something that’s going to be a livable wage. But the entire time that we had been married, my husband and I had always joked about writing a book called Priestdaddy if we were ever in just the direst financial straits. He was like, “Everyone will want to read this. Everyone will want to know what happened.” But I had never thought about it, and I’m not the sort of person to write a memoir, but sitting in that house and thinking, What are we going to do? It was just the obvious thing. But it was just never something I’d wanted to do. But then, as I was living there, it began, the scenes with my parents began to flash out at me as scenes. I found a way where I could do it, and sort of still remain myself and continue to protect myself also. It always seemed very exposing to me. It was never an idea that it was a lesser genre or something like that, there’s just a sense where I don’t like to be exposed.

One other thing that feels important about your memoir, in particular, is that it doesn't take place in New York. It's refreshing to have this viewpoint, but I feel like it's so rare to have someone like you, not from the coasts and without the formal education we expect from writers, to have her voice heard.

It feels absolutely strange to me. Certainly, not all writers need to live in New York. I mean, I like New York when I visit, but it’s all a little fast for me. A person like me should not necessarily live in a place that is paced so much faster than my own experience of the world. We do have to have writers that live somewhere else. We have a very strong regional tradition in America that you wonder if that’s slipping away a bit because we’re just flying to the coasts as soon as we can. Like definitely, get out if you want to. But you can come back to these places and describe them to the rest of the world. If we lose that, then I think we lose a very large part of our literature and what makes American literature so interesting, so special.

When you finished this book, what did you feel like writing it had given you?

To be very honest, I felt almost completely dead when I finished the book. I wasn’t just working in bed, I was almost completely flat, just raising a single finger to type. I’m not sure why it took so much out of me, but, by the end of it, it was almost like it was hard to know whether I could just stand up and walk like a normal person. I’d put so much into it. When you finish a book like this, maybe one or two people have read it, you don’t know what anyone else is going to think. You don’t know if you achieved everything you wanted to achieve or if you’ve said everything you set out to say. So you have this period of re-entering the world where you’re a little bit of a zombie, you’ve dived back into your past and maybe stayed under it a little too long, so you come out of it and the world just looks strange.

Writing is singularly draining considering how little of your body is actually engaged.

It’s truly silly to say that! Like, ["writerly" voice] “Truly writing is one of the most physically draining things you can do.” Because it’s like, "No, Tricia, people are out there mining for coal." But, at the same time, in my experience, when you’re writing something really heavy and serious, it’s almost as if you have been carrying stones up a mountain. And I’m not sure why that’s true. [Laughs] It sounds ridiculous! I know how ridiculous it sounds. But it’s always been my experience.

Priestdaddy is available for purchase now.