Entertainment

Ariel Levy On Loss, Love, & Privilege Of Expression

“Embrace the experience that’s yours”

Within the span of a handful of weeks, almost every identifiable structure in Ariel Levy's life was summarily dismantled. Where once she had been married, a homeowner, five-months pregnant, and on her way to motherhood, in one swift rush, she... wasn't. When once she had been sure of the direction in which her life was heading, straight and strong as an arrow, over the course of mere days, her certainty vanished; the arrow arced up and into the kind of wide open sky that's hard to accurately assess. Is it darkening or growing lighter? And does it even matter what color the void is?

In one fell swoop, Levy had lost her child, her wife, her house; all key elements of the person she had worked to become, all parts of a life she had intentionally created. This type of loss can seem too much to bear, and sometimes it is. But Levy was, as she'd be the first to tell you, left with some things still; chief among them, her ability to write.

On staff at The New Yorker for almost a decade now, and a writer for New York Magazine for years before that, Ariel Levy has written notable profiles on everyone from South African athlete Caster Semenya to right-wing Christian politician Mike Huckabee and iconic writer Nora Ephron. Her ability to tell someone else's story appears born out of a genuine curiosity about others' lives; her writing is singularly lucid. In Levy's profiles, her subjects come to life in a brilliant, sensorily complete way; we don't just come to understand the way Ephron thinks and works, we see how Ephron exists in the world: "When she is sitting, Ephron folds in on herself—she crosses her legs and holds her chin in her hand—and becomes very compact, a little origami of a person."

Levy's love of specificity, her commitment—and well-honed talent—to putting into words those parts of a person that seem beyond expression is a gift, one that can feel surgical in its precision, but almost spiritual in its ability to translate facts into something bigger than a simple reflection. Levy allows readers to become a part of realities that are not their own, if only for a little while.

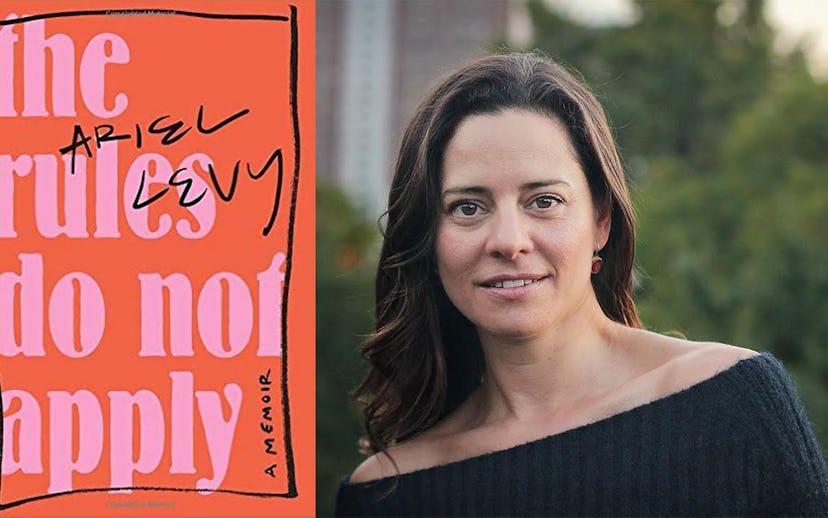

But while Levy built a career writing mostly about other people, it was a piece she published in the New Yorker in 2013, "Thanksgiving in Mongolia," a personal essay about the loss of her child, which quickly became not only what Levy would be primarily known for in many circles, but also what would become the basis for her new memoir, The Rules Do Not Apply. In it, Levy recounts the aspects of her life which led to her finding herself at the "edge of the world," mourning the loss of her son and her life as she thought she knew it. Levy explores the advantages she was given growing up, the privileges inherent to being the type of person who was sure she could do anything, and then finding out as she got older that there is no such thing as getting out of this life unscathed, that, in fact, a key part of life is experiencing pain and grief.

It can be tempting to look at Levy's life and dismiss the tragedies she's experienced because she is also an incredibly privileged person in terms of everything from her professional position to the opportunities she's had—and seized—since birth. But to dismiss Levy's writing out of hand would be short-sighted, and denies the singularity of her experience as well as the universal appeal of how she writes about it. Plus, frankly, playing the privilege wars with someone who freely and frequently owns up to her privilege means you've kind of lost before you've started.

And too, grief does not care how much money you make or if you're a beneficiary of white feminism; it comes for everyone. It puts a space between you and the rest of the world. It is a space of loss, of pain, of torment, and anguish. It is a space that is almost impossible to bridge, to translate into anything other than an emptiness. But still, we try. It is human to try. And Levy doesn't just try with her book: she succeeds. Levy treads well-trod ground in writing about the loss of home, love, and a child, but rarely has the lonely space of grief—particularly as it pertains to womanhood—been rendered so plainly and beautifully as it has been here. The power of Levy acknowledging that the 10 minutes she was a mother were the most important 10 minutes of her life—these are words that have stayed with me in the four years since I first read them. Levy's ability to put her grief about the loss of her child, dealing with the substance abuse issues of her spouse, and coming to terms with aspects of her complicated childhood home life into a book that will not only stick with whoever reads it, but also could prove helpful for those who feels alone with their grief, as Levy once did, is a tribute to what good writing can do—make people, including the writer, feel less alone in their pain.

As Levy told me when I spoke with her recently, about how I'd read "Thanksgiving in Mongolia" out loud to my boyfriend on a long car ride (which, yes, he did almost drive off the road):

One of the things about that story is that there were some more virtuous goals for this, but one of the things was just, "I need help carrying this burden. I need to share this." And it worked. People have been really giving to me about it and I really appreciated it. It feels really good to have people say, "I feel that." You're sharing your experience and you get something back from people. It's just been a beautiful thing.

Well, to be honest, the first thing Levy said after I told her I read that essay out loud to my boyfriend was, "Jesus!" Because Levy is prone to talking in exclamation points and italics; her energy—even on a phone call—is infectious and unwavering. She punctuates her speech with "Girl!"s and she curses, and the openness with which she expresses herself on all topics—from her opinion of Huckabee and his "burning resentment" to a negative assessment of her book—is a journalist's dream. And much in the way her book deals with the most serious of topics but is never self-serious, Levy often seems to have a laugh lurking in the back of her voice, and speaks emphatically about the things she believes in; she is the same forceful young girl she describes at the beginning of her memoir as always being "too much" for everyone, only all grown up.

And I get how this can rub some people the wrong way. I understand how some of the things she can say or some of the things she's written might make people cringe, but that discomfort ignores the fact that Levy has never tried to explain away or apologize for any of the realities of her life, and would never dismiss other people's realities out of hand in the same way hers has been. Rather, Levy explains to me how she has come to believe in "embrac[ing] the experience that is yours"; in her case, the ability to do so has resulted in a book that is a small, stunning, sometimes morbidly funny, never sentimental look at one woman's experience realizing what it is to feel pain, to feel love, to feel alive.

Below, I talk with Levy about her memoir, being a writer, and when it is, exactly, that a person can expect to stop grieving.

It struck me how relatively quickly you wrote "Thanksgiving in Mongolia" following your experience giving birth. [The essay was published in November 2013, one year after Levy had been in Mongolia.]

Well, and I wrote it quicker than you realize. Like, we didn't publish it for a year, but it was written before that.

It was such a departure from so much of your other writing because it was no a profile of someone else; it was about you. Why did you feel like you needed to write it?

There was no thinking involved; it just sort of came out of my fingers. I've never had a piece like that before, where there was no thinking. I don't know how else to put it. That was why I wrote it. One reason why I published it, is because most women will have some experience at some point that's super intense around menstruation, pregnancy, child birth, the loss of a child, menopause, something around this stuff of being a human female animal, and I just thought, You know what? Goddamnit, this is a legitimate subject for literature. And the reason it icks people out and is barely written about is misogyny, and I am supposed to be a feminist so, you know, I'm going to publish this.

And the other reason was that I just felt the need to express this. I basically had an identity crisis after that. I felt like a mother. A switch had flipped in my heart. And my body. I was lactating. I felt like a mother, but I had no child. And that's a kind of identity crisis. And so by publishing it, I was announcing to as many people as who cared to read it, "This was my experience of motherhood." And that felt good to me. And I sort of justified it by saying, "I bet there are other people that felt this too."

And I am happy that I heard from so many women. Like, lots and lots of women who had had miscarriages and who had had still births and who had lost children. I don't know how to say this without sounding really corny and gross, but it's been a beautiful experience, feeling connected to readers. Specifically women. Men too have written, but feeling connected to women through that piece has been a really gratifying experience. A real "the personal is political" kind of thing.

Do you think that the difficulties you'd feel when people wouldn't really comprehend what you had been through [when they tried to relate by talking about their miscarriages, which were different than the experience of giving birth at 19 weeks of pregnancy to a child who would die within minutes], did that become better after publication?

That's part of why I wanted to write it. "Oh, you had a miscarriage." And it was like, "Yeah, not exactly... that doesn't really quite capture it." And so I wanted to speak my truth? And I did.

I really loved that you addressed that kind of anger, which is also part of the overwhelming grief you were experiencing. It's not exactly anger, but it's a need to mark down what it is that you're actually feeling and get it out there.

And that's what writing is supposed to be about, isn't it? You're trying to capture the specificity of experience, and the specificity of character. Well, I felt uniquely qualified to write about the specificity of my character. I know myself better than most people know me. You know, I've been this person for 42 years, and I felt like, first of all, if I heard my story and it was about another woman, I would want to write about it because it touches on a lot of the issues that are important to me, that are the focus of my career. So I was like, "Why would I not tell this story, just because the person at the center of it is the person I know best, you know?" [Laughs.]

You always wanted to be a writer; how does that manifest itself from a very young age?

I don't know how to explain it except to say that I had that desire; that's what I wanted to be. That's what, when I would fantasize about a life or a character for my grown-up self to be, that was my fantasy. And also, I just liked the activity. I just liked writing, and it felt natural for me to do all the time.

Rules are an ongoing theme of the book, and I was wondering what was the point in your life when you realized that other people's rules were not something you needed to live by?

Well, I was raised with that set of beliefs. Like, my mom, as I wrote about in the book, had this boyfriend who was always around. I didn't see that at my other friends' houses, that there was another person in the relationship, besides both parents, who was around all of the time.

That was very unorthodox!

Yeah, that was very unorthodox and very suboptimal for me. Actually, for everyone. For my mom too; for all of us. But I think they had these ideas, coming out of the '60s, of like, whatever the establishment told you was right was to be questioned. So much of it was bullshit, probably all of it was bullshit, and needed to be tested. And I think that's really what their mission was, and that's really what they were thinking about, and so that's how I was raised. Like, I didn't come up with it. They did. And in fact it was not very rebellious of me to take that point of view, it was what I was taught—that rules were there to be questioned, and that whoever made them, it was probably always in their own interest that these rules were made. It wasn't until the sort of Mongolia of it all that I really realized, "Oh, I'm mortal." Those are rules that apply. I'm going to die. My fertility is going to expire—and it has. My baby is not going to live. All that. That nature has the last word, always.

Early in the book, you touch on that feeling a little bit when the air conditioner drops out of your window...

Yeah, it was like a tiny little flash of it.

But it's so hard when you're still in your 20s to think that something like that means more. Because we do usually wind up getting out of those situations that test our faith in our own immortality. And then we can forget about it.

I can't remember what publication, but somebody just wrote a thing, and the author was so angry at my book, saying what a privileged kind of view that is, and the only thing I would counter to that is, "Yeah! That's what the whole book's about. That is a privileged point of view. Absolutely."

That review seemed to really miss the point, which is that there's no point in your book where you're not saying exactly that.

No, I agree, but it's one of those things that didn't bother me, and this is going to sound really condescending, but, so what? I don't think what she's saying is right, but whatever, it's fine. I can take it. I can totally take it.

Yeah, you know, you've been through worse!

[Laughs] I definitely have. That's exactly right.

You wound up in Mongolia, in a marriage, a homeowner, and about to have a child, which in so many ways are all the traditional parts of what a woman is supposed to be doing in her mid-30s, but you were doing them in completely your own way. But then everything fell apart. Was there ever any time where you were like, I wish I had paid more attention to this specific way of being?

Oh, yeah! While I was grieving? Big time. I don't feel that way anymore; I feel like the life I ended up with is pretty great, and it's frankly not that surprising it's my life. If you put all your energy into being a writer and having adventures, if you end up being a writer who has adventures, well, it's not that shocking. But, yes! God, yes. When I was grieving, I was battering myself. I was so angry at myself, for putting myself in that position. So that it was like, "Great! Now you're 38 and childless and alone. Good job, girl. Way to think this one through. Way to plan it out." I was so angry with myself. You have no idea.

Grief does to us; it allows us to turn our anguish in on ourselves.

My first girlfriend, Deb, told me during this time... she's a Buddhist, there's this concept in Buddhism, the second arrow. Like, the first arrow is whatever hurt you, whatever pierces you, but the second arrow is when you shoot it into yourself because you're angry at yourself for putting yourself into the position where you take the first arrow. I mean, I'm not saying that quite right, but that's the idea. And that went on for a long time because I kept trying to have a kid, and I couldn't. So that was an ongoing agony for years.

How did you get out of that?

I liberated myself. I liberated myself by accepting reality. By saying, "You know what, I have to mean what I say in this book." Like, I actually have to live like it's the truth. I have to say, "Okay, I don't get everything. What do I get? What can I be grateful for?" And there's a lot! And so I liberated myself from the agony of "I don't get to be a mother," by focusing instead on what I do get. And it's a lot. And so people are like, "Is this book a warning? Or a cautionary tale?" But for this book to be a cautionary tale, I'd have to be saying, "Be careful or you could end up like me." And the fact of the matter is, I don't think it's so bad ending up like me. I'm really happy.

One thing I really loved was how the book ended without some sort of neat, wrapped-up ending.

Wouldn't it have been disgusting? Wouldn't it have just been so disgusting?

It would have been a little Eat, Pray, Love, which is fine, but...

Oh, yeah, yeah, it's fine, but, in my case, it would have been extremely misleading. It's technically the truth to say that John [Gasson, the South African doctor Levy meets in the hospital in Mongolia] and I then fell in love and still are very much in love, but to put that at the end of that book, even though it's technically true, it would have been profoundly misleading, because it would have been like saying, "And then one day my prince came and saved me from my sorrow and my lesbianism and my economic situation," and none of that is what happened. It's like, falling in love with someone else didn't take the grief away from losing my son; it didn't take the grief away from my last marriage failing; it didn't do anything except open up a beautiful new part of my future, which is great! But it didn't fix anything.

Not dwelling on pain doesn't mean the pain isn't there.

I couldn't agree with you more. At first, I think, grief is something that you live in; like, it's literally the air you're breathing, you're literally inhabiting grief, it's something that you live within. And then eventually, it's something that lives within you. And that's not a bad thing. Grief is there for a reason, and it can be really good for a person. It hurts. It's a horrible feeling, but it can do good things to your human project.

I don't think that there's anything useful in trying to deny it's existence since pain is so essential to being human.

If you want to live on planet Earth, the price you pay is loss along the way. And grief. And that's just the deal. I think Roger Angell, in his essay called "This Old Man," has written beautifully about this.

It sounds like you came to terms with your grief, but I couldn't help but wonder a while back, when I saw that you'd written an article on ayahuasca, how scary it must have been to risk reliving all of it. Were you terrified of doing it?

Yup! I was scared shitless. You can imagine my surprise when I did not see the jungle or my son or my ancestors or my own death. All I saw was lots of vomit. It was such an anticlimax! It was ridiculous! I was totally disappointed. But then I was like, well, the message of this book, I hope, is to embrace the experience that's yours. But with the ayahuasca, I was like fuck, this isn't working. But then I was like, you know what? This is going to be a funny article. Stop complaining. Enjoy this. It's great. You're so lucky that there are people vomiting on you right now!

The Rules Do Not Apply by Ariel Levy is on sale now.