Life

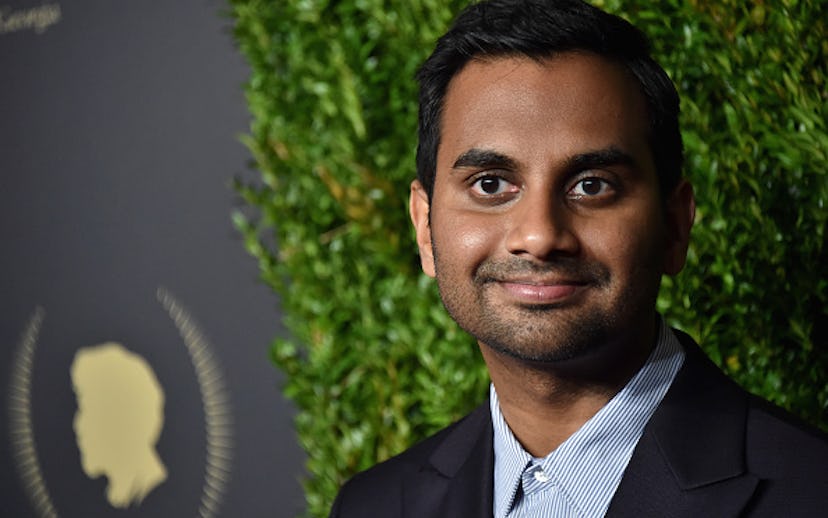

On Aziz Ansari And Rape Culture’s Generation Gap

Why can’t we hear each other?

On Saturday night, a little after 11, I showed up, a little tipsy, to the apartment of a man with whom I’d previously been on two dates. This—my showing up to his home late at night—would be our third “date.”

When I got there, he told me a story had just come out, with allegations against Aziz Ansari. I asked if I should read it, and he said no: “You will not want to be around a man after you read it.”

We sat in his living room talking, and when my voice got too loud, he gently reminded me his roommate was asleep just behind us. I asked if we should go to his bedroom and he quickly said no, the living room was fine, as long as we spoke softly.

Later, after I’d read the Ansari story on a website called babe, I thought about that interaction. I was touched by what I interpreted as my date’s apparent preoccupation with Ansari’s bad behavior, and seeming determination not to repeat it. I was pleased with him for—as I saw it—internalizing the inherent lesson in the piece: that a woman agreeing to be in your apartment, no matter the time of night, does not automatically mean you are granted all-access entry to her every orifice. Though my position with him—for reasons including age and power dynamics, among others—is very different than that of “Grace,” the anonymous 23-year-old who shared her experience with Ansari, it was hard not to feel a connection.

This shared connection is one reason that this story has raised a lot of questions and caused a lot more divisiveness than other stories about celebrity sexual misconduct. Chief among them: Was this assault? Or was it merely a bad date?

These questions are compounded by some major flaws in the way the story was reported. There’s a childishness to the narration, as when the writer makes a point of approving of Grace’s outfit for the night, and an excessive attention to details that detract from the actual experience, like the emphasis on Grace not getting to choose what kind of wine she drank or referring to a particularly galling move of Ansari’s by the nickname “the claw.” The site also only gave Ansari five hours to provide a response to the article, and when they did finally include it, they repeatedly made a fuss about how he took “31 hours” to provide one. Giving someone a day to respond to serious allegations is not unreasonable, and responsible journalists know that even people accused of bad deeds need to sleep. Further, the hyperbolic headline declaring it “the worst night of [Grace’s] life,” combined with immature storytelling that focused too exactingly on a play-by-play of the date, made it seem like an attention grab, an attempt by an unknown publication to make a name for itself.

These are not just petty quibbles about the piece. It is these things that were seized upon by Grace’s detractors and Ansari’s defenders as ways to discredit the story, hampering an opportunity for an important discussion about an experience that resonated with so many women—even women who disagreed with deeming what happened “assault.” The play-by-play storytelling seemed to have the effect of making it a (bad) sex story instead of one about power and abuse.

Maybe this is why so many women have been so eager to defend Ansari and shame his accuser. There’s a sort of pity for watching someone be publicly humiliated as being bad in bed. HLN TV host Ashleigh Banfield read an open letter to “Grace” on her show, chiding the 23-year-old: “What you have done is appalling. You went to the press with your story of a bad date, and you have potentially destroyed this man's career over it." Caitlin Flanagan, writing in The Atlantic, also bemoaned that Grace and the babe writer, Katie Way, “may have destroyed Ansari’s career.”

The logic here escapes me, because if Banfield and Flanagan really believe this was just “a bad date,” it’s unclear why or how it would ruin a man’s career. If anything, being bad at dating is pretty on brand for the characters Ansari plays and writes for himself.

New York Times opinion writer Bari Weiss goes further, citing babe piece’s capability for destruction, calling it “arguably the worst thing that has happened to the #MeToo movement since it began in October.” Beyond taking down Ansari, the story apparently also has the ability to take down a social movement.

This is disingenuous of Weiss. Her piece is a pretty tedious recapping of Grace’s story, with a significant omission—the moments preceding Grace telling Ansari, “You guys are all the same.” These words come after he acknowledged Grace’s discomfort and suggested they “just chill, but this time with our clothes on.” But these words come because Ansari is still forcing his tongue and fingers into Grace’s mouth. And yet Weiss paints Grace as a petulant child for uttering them, removing the context which explained well why they came out.

This is a common problem with much of the contra-#MeToo writing. It is mean-spirited, belittling, condescending, and it refuses to acknowledge context. The tone it takes detracts from any substantive message. Flanagan’s Atlantic piece was especially charged with this. The anger and hatred in it is confusing. So much so that I find myself curious about its roots, how that anger and hatred grew in those writers. It feels like a generational gap. I want to tell them they don’t have to be so defensive anymore. We’re changing the game! You’re allowed to have feelings now! You’re allowed to express them, and expect that they be considered! Things can be complicated! Men can be shitty and not rapists!

This came up frequently in the criticism of the fabled Shitty Media Men list, in which men were charged with wrongdoings ranging from assault and “not taking no for an answer” to “creepy AF in the DMs.” Critics of the list seemed unable to accept that the most powerful version of the discussion we wish to have is going to be all-encompassing, and therefore nuanced. We want to talk not only about the men who are obvious monsters, rapists in the eyes of the legal system, but also those who were, as the list described them, “shitty” in ways that harmed our careers and day-to-day lives.

Weiss sees Grace’s vision of consensual dating as “retrograde,” but then takes a very retrograde, binary view of sexual assault as something that can only have occurred if the victim vigorously fought off her attacker. Weiss thinks Grace wanted Ansari to read her mind. She thinks Grace needs to learn to speak up. A few of my feminist friends privately said the same. However, though Weiss acknowledges the need for sexual and dating dynamics to change (“Shouldn’t we try to change our broken sexual culture? And isn’t it enraging that women are socialized to be docile and accommodating and to put men’s desires before their own?”), she then pins the responsibility for that change on young women. She doesn’t want us to push men to be more perceptive, more attentive, more interested in our feelings and pleasure.

I’m surprised more men aren’t offended by this view. It’s demeaning to them. They’re not incompetent simple organisms incapable of complex thought. I am one of the last people to champion the intelligence of men, and even I believe they have a greater capacity for emotional and intellectual discourse than the average cactus or ottoman.

This is what Weiss and her cohort return to over and over again, the idea that it’s on women to fix dating and sex. That men can’t be blamed for “normal” behavior. That because an experience is common, it’s not that bad. But a one-sided approach to “fixing” dating and sex is not going to work. The truth is, sex and dating would be so much more fun if we are all saying what we feel, caring about how the other person feels, and trying to have the best time possible, with the understanding that it’s not a good time if only one person is having it. A lot of men are ready to get on board with this; I really believe that.

Weiss and Flanagan seem to see the Ansari story, and other elements of the Me Too movement, as insults to their version of feminism. That’s historically predictable. Every wave of feminism has been annoyed at the one that followed, has aggrievedly shouted, “That’s not what we said! You’re doing it wrong!” And every new wave has shrugged, like a generation of headstrong teenage daughters, and insisted on doing things their own way.

Let me be clear: We are grateful to the ones who came before us. We are grateful for the work they did that allows us, today, to be this audacious, to feel this entitled to live our own truth. We are inevitably going to seem too radical, as they did to the ones who came before them. We are inevitably going to makes messes, to stumble, to be sloppy on wobbly colt legs, as we try to figure out what we want our world to be. But you do not need to panic. We are not going to allow one misstep—or one story that you and others see as a misstep—to derail the progress we are making.

Wanting men to spend some measure of time and energy considering the feelings and experience of their sexual partners is not a huge ask. The burden of such consideration has long been the purview of women, and because having that awareness and curiosity is typically uncomfortable, some feminist thinking concluded that the best path forward was simply to quash it in ourselves.

This approach makes the same mistake that criticism of things like the Shitty Media Men list did: It seeks perfection where there is no possibility of attaining such an ideal. Sex is messy. Humans are messy. This is part of why reporting on these issues is such a delicate, tricky process that can’t be rushed the way babe seemed to. Even so, in its imperfection, babe’s story shed light on a conversation we need to be having—both in private and in public. This is evident from the number of men and women discussing it online, and the impact it appeared to have on my date the night the story was published.

I don’t know exactly what that impact was; I hadn’t read the Ansari story at the time, so I couldn’t ask. It’s entirely possible I misread my date completely, projected some kindness onto him that wasn’t really there, like the main character did in The New Yorker story “Cat Person,” which many have compared to babe’s Ansari story. But I’m looking forward to asking soon, and grateful for the opportunity created by the public discussion. The public discussions are invaluable in prompting the private ones, making them slightly less awkward, ideally helping us all feel a little less defensive and a lot more curious.

I hesitate to use the phrase “rape culture” because I have grown to hate it. Like many catchphrases that fall prey to overuse, it seems to have lost all meaning, if it ever had any. But our culture is one that is conducive to rape in many ways, and one of those ways is our aversion to acknowledging ambiguity or nuance, those shades of gray that characterize the majority of our interactions.

The day after their encounter, Ansari apologized to Grace when she confronted him in a text message. “I’m so sad to hear this,” he writes. “All I can say is, it would never be my intention to make you or anyone feel the way you described. Clearly, I misread things in the moment and I’m truly sorry.”

This apology is inadequate, though it appears earnest. What would be truly beneficial is something resembling a dialogue, something that involved Ansari interrogating his own behavior, and how or why it was so easy for him to “misread things in the moment.” This moment of reckoning we’re in is about looking critically at what we’ve allowed to persist for so long, and why. Dismissing the babe story as “normal” or “just a bad sexual encounter” is only going to make it inevitable that heterosexual men and women continue to have bad sex and hurt each other, often without really understanding why or how or the ways in which things could be different.