Entertainment

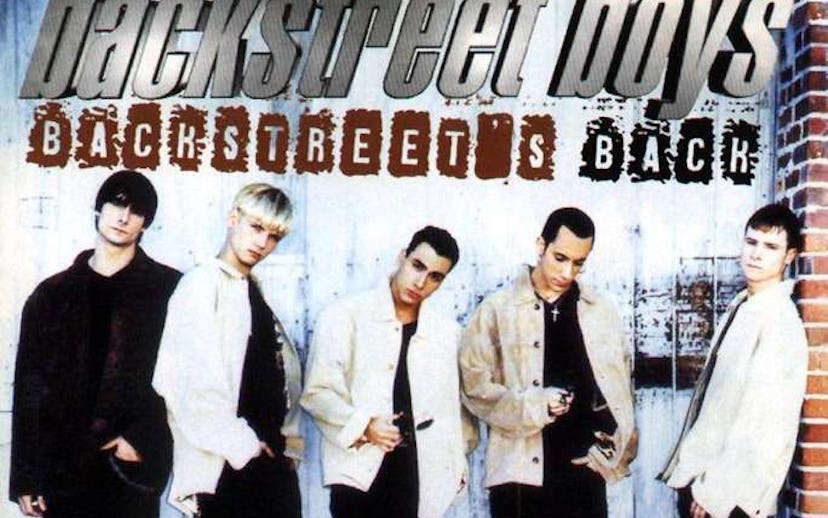

‘Backstreet’s Back’ Turns 20: A Tribute To The Original Faux Soft Boys

And how other male pop stars followed in their footsteps

On August 11, 1997, the announcement was made in the form of an album title: Backstreet’s Back. And with the release of the Backstreet Boys' sophomore album came the introduction of the faux soft boy. Which was a feat, because in the years since the demise of New Kids on the Block and the diminishing presence of Boyz II Men, BSB began to fill a void in the pop world that had been previously defined by grunge and rock. Their music was emotional and catchy, and each member danced while adopting specific personas. They encouraged their listeners to “get down” while promising they’d never break your heart. In the years that followed, the majority of male pop performers have been modeling their own careers in the Fab Five’s likeness.

It's not that BSB were mavericks—they were just a little more obvious in their capacity for fuckery than their predecessors were. Boy bands and their verses of devotion have existed since the 1950s (spoiler: The Beatles are most definitely a boy band), but as NKotB signaled the death rattle of bright and shiny Top 40, pop became increasingly defined by acts like Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Alice in Chains, Smashing Pumpkins, and eventually Foo Fighters. Which meant that when Lou Pearlman recruited Nick Carter, Brian Littrell, Kevin Richardson, A.J. McLean, and Howie Dorough to form the Backstreet Boys, they were relatively unique. Like Boyz II Men, they could harmonize and deliver ballads (see: “I’ll Never Break Your Heart”), but unlike the Philadelphia group, they weren’t a bankable R&B group who’d been going since 1985. Like NKotB, they toed the line with their explicit lyrics (see: “Get Down”), but they weren’t as overtly rebellious. And like Marky Mark, they showed off their moist-looking abs but kept button-ups on to maintain a barrier between themselves and their fan base.

And so the faux soft boy (and/or fuckboy) was born.

By the time Backstreet’s Back was released in 1997, the group’s mandate was clear: They loved women unless they wanted to have sex with them. Songs like “As Long As You Love Me” touted the importance of unconditional devotion (“I don’t care who you are, where you’re from, what you did, as long as you love me”), while “That’s The Way You Like It” was about an overt attraction to a relative stranger (“Oh mystery lady, you’ve got somethin’ I like, you’re dangerous, oh baby, could you do me right?”). “Like A Child” placed their subject on a goddess-like pedestal (“Girl don’t stop the sun from shining down on me, ‘cause I can’t face another day without your smile”), while “Backstreet’s Back” was simply a “Thriller” rip-off used to announce their capacity for doing it (“Am I sexual? Yeah!”). It also didn’t make a ton of sense.

Which is the calling card of today’s faux soft boy, as we know it. As BSB’s career progressed, singles like “I Want It That Way” positioned themselves as heartfelt confessions of vulnerability, but in retrospect, made absolutely no sense (“But we are two worlds apart, can’t reach to your heart when you say, I want it that way.” #WTF). Meanwhile, “The Call” was a song about how communicating with a human woman ruined a night out with the boys. Ultimately, it was “Hotline Bling” without quite as much shaming.

But in the mid-to-late '90s, we’d yet to place artists like the Backstreet Boys into a real-life context. Without social media and a better eye into their carefully constructed personas, BSB (and boy bands like it) could position themselves as Men Who Really Cared™—unless you were someone they only wanted to sleep with, or you dared ask to be more than an entity to worship. We’d yet to understand the way their personas (the bad boy, the sensi-soul, the baby, etc.) existed to reflect aspects of a whole person, and we’d yet to really question why in one song a group could claim their love was “all they had to give” while equating that only good sex existed at the hands (or whatever) of a bad boy. (See: “If You Want It To Be Good, Girl (Get Yourself a Bad Boy.)”)

And those myths laid the groundwork for the pop stars we’ve embraced since. Justin Bieber built an empire on being able to vulnerably beg a woman to be his girlfriend (“Girlfriend”) in one song before listing her faults in the wake of a breakup in another (“Love Yourself”). Drake’s career hinges heavily on lamenting over lost loves before having a tantrum over their arguments at The Cheesecake Factory. Justin Timberlake shamed Britney Spears via “Cry Me A River,” after using “Like I Love You” to spew "good girl" rhetoric (“You’re a good girl, and that makes me trust ya”). And even One Direction sang the merits of a “natural” woman who doesn’t “need” makeup, before saying outright that they weren’t sticking around for more than a hookup in “Perfect." So even if a group boasts more than a couple members, the collective represents two distinct faces: a guy who’ll love you forever, provided you play by the rules he’s set for you.

Which isn’t to say Backstreet Boys are bad or that Backstreet’s Back is a bad album. Far from it: BSB helped clear the way for two decades of pop-as-bankable-music, and “Backstreet’s Back” is a jam. But their fuckboy legacy is also as prevalent as their capacity for releasing hits, and, as influential pop stars, that should be noted. Especially as so many male pop stars continue to tow a line attached to the very real idea of framing love interests as either goddesses or foes.

It’s interesting that while so many male pop stars can exhibit complexity in their choreography or social media presences, they’re still stuck in the second dimension when writing about women, as if “good girls” can’t “get down.”