What was it that Tolstoy wrote? I think it was something along the lines of: All good apologies are alike; each bad apology is bad in its own way. Maybe I'm paraphrasing, but the point stands. Good apologies are good because of what they have in common. They tend to be succinct, sincere, and focus on the way that the aggrieved party was hurt, in an attempt to mitigate that pain. You'll know a good apology when you hear it, because it will actually make things better. An apology, then, is good when it works as intended; the problem is identified, amends are made, and a foundation is laid upon which people can move on from their pain and work toward something better. All good, right? Right. Sure. And then, there are bad apologies.

You don't need to search very far to find evidence of bad apologies these days. They're everywhere you look. In fact, it's pretty fair to say that 2017 is the Year of the Bad Apology, with each new entry into the bad apology canon being unique in its ability to make an already terrible situation worse. Think back to the very beginning of 2017, when countless "woke" white women took it upon themselves to apologize for the fact that 53 percent of their demographic voted for Donald Trump for president. This type of apology is the most cringe-inducing type of performative wokeness, and the fact that the apology was also commodified, i.e. made into t-shirts, made the apologies, such as they were, even worse. (Pro tip: Finding a way to make money off of the horrors of white supremacy is the basest form of exploitative capitalism.) Perhaps the most horrible thing about these apologies, though, was that they were actually focused around those making the apologies; they only served to make those apologizing feel better about themselves for having apologized. This, then, is something that most bad apologies have in common: They center the person or people making the apology, thus further marginalizing those who have been hurt.

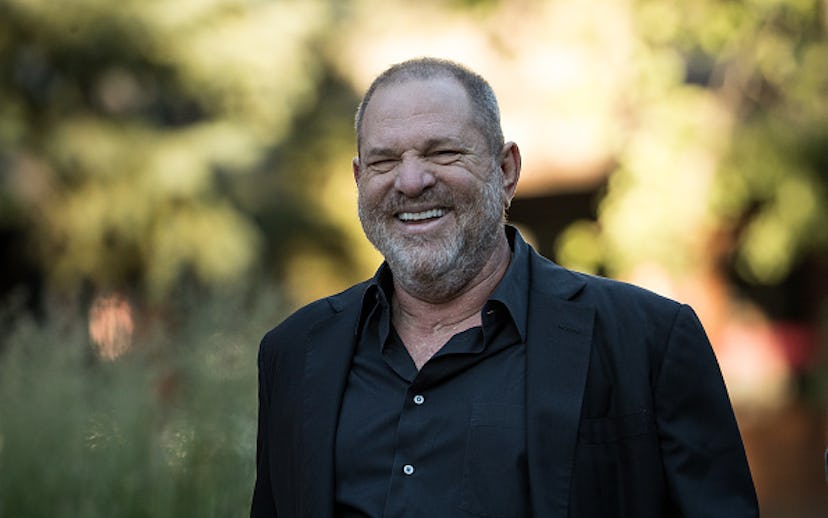

Nowhere is this more evident than in recent bad apologies made by bad people like serial sexual predator Harvey Weinstein, whose statement, following recent revelations about the dozens of women he'd allegedly harassed, assaulted, and raped over decades in Hollywood, is a perfect example of a bad apology. In the statement, Weinstein attempted to excuse his behavior as being typical of the time in which he was raised (the classic refrain from misogynists and racists, alike!), but then, in a twist that nobody could have seen coming, ended his apology by deflecting blame from his atrocities onto those of... the National Rifle Association? Which, look, I hate the NRA and think it's a terrorist organization as much as the next person who didn't grow up thinking the Second Amendment gives them permission to stockpile semi-automatic weapons, but there's a time and place to talk about gun control—and a formal apology to the many women whose careers and lives you've irreparably harmed just isn't it, Harvey.

Then yesterday, actor Kevin Spacey issued a non-apology of his own, in which he took the opportunity of being accused of having sexually assaulted actor Anthony Rapp, when Rapp was 14 years old and Spacey was 26, to publicly come out as gay. Spacey also used this apology as an opportunity to redirect the narrative away from his misdeeds and onto another topic; in this case, it was a confirmation of the longstanding, but never confirmed, belief that Spacey is gay. That Spacey would do this, thus forever tying the pedophilia accusations leveled against him with his homosexuality is particularly despicable, as it only serves to fortify erroneously but unfortunately widespread, bigoted ideas about being gay.

Earlier this month, The Outline's Laura June wrote about "the performative apologies of very guilty men," and noted that bad apologies, like that of Weinstein, "carry with them the truly mind-boggling suggestion that we—the public, the reader, the company shareholders, whomever—are concerned about the welfare of the guilty." This goes beyond merely placing the apologist at the center of the apology and makes for a situation in which those on the receiving end are being asked to do work in this situation and, in effect, sympathize—or at least empathize—with the wrongdoer, which negates the purpose of an apology in the first place, namely to atone for misdeeds and assume responsibility. But there was no assumption of real responsibility in someone like Spacey's apology, in which he claims not to have remembered doing anything wrong and blames alcohol for making sexual advances on a young teenager.

It shouldn't be surprising that we reached a nadir in this type of public discourse this year. After all, 2016 featured one of the worst apologies of all time, when Trump excused his "grab 'em by the pussy" comments by saying it was mere "locker room talk." And in Trump, we have one of the most unapologetic personalities of all time. Every accusation gets dismissed as "fake news," and accusers get called liars. Even when Trump has apologized, like he did with the pussy-grabbing comments, it's clear that he doesn't mean it, just as it's clear that Weinstein and Spacey only apologized because they were caught, not because they're truly sorry.

So where does this leave the apology then? Is it even necessary? There is, I'll admit, a part of me that doesn't want to hear them anymore. I don't actually care if Weinstein is sorry. Unless he can make actual amends and repair the damage he did to dozens of women's well-beings—not only emotional and physical but also professional—who cares if he feels bad now that his own career is threatened? In fact, these types of apologies are meaningless unless they effect change for the victims, and for a long time, there was little hope that they would actually do so.

But perhaps that's not the case for much longer. In her piece, June concludes:

In the past, powerful men were assured multiple opportunities to rehabilitate themselves, their careers bruised by improper conduct with a woman, perhaps, but certainly not destroyed... But the fact is that women are no longer silent or unheard. The flood gates are, for now, open. Men still suck at admitting their crimes, and they still do not know how to draft an apology. Their sense of entitlement to the world remains—according to a recent report, Weinstein still believes he will be given a "second chance" in Hollywood. But their words and opinions don’t seem to matter that much anymore.

The thing about these types of apologies by powerful individuals or groups is that their main purpose is for the wrongdoer—whether it's privileged white women or sexual predators—to be able to move on with their lives unimpeded, not so that the victims could. Now, though, with more and more people feeling like the important thing isn't to get a mere "I'm sorry," but is to instead publicly demonstrate the incredibly wide reach of systemic problems like sexual assault, misogyny, and white supremacy, perhaps things actually will change for the better. An apology can't be used to cover up bad behavior anymore; it can't be used as a distraction from the problems it reveals. For an apology to be effective now, it must be followed by action, by a dismantling of everything that made apologizing necessary in the first place. To paraphrase another great wordsmith, it is too late to say sorry, but that doesn't mean it's too late to change the problems around us.