Beauty

Prettier And More Popular: On The Nostalgic Appeal Of Beauty Advice From The Past

Looking back at ‘Betty Cornell’s Glamour Guide for Teens’

It works like a magnet, this book, attracting virtually every person who stands in front of my bookshelves, perusing the titles with varying degrees of intensity, until their eyes inevitably settle on the same book that every other person's eyes have also stopped on: Betty Cornell's Glamour Guide for Teens. "What is this?" everyone asks. They start flipping through its now-crumbling pages, quickly absorbing the tips on diet, posture, personality tweaks, and the appropriate haircut for various face shapes. Its advice is antiquated, as clearly of another aesthetic era as are the Playboy magazines of that time. But, as with those old nudie magazines, the distance of decades has imbued in it a nostalgic sense of charm; there's something compelling, instead of repelling, at being offered skin-care advice from a time before #shelfies. And so the first question is quickly followed up by another: "Can I borrow it?"

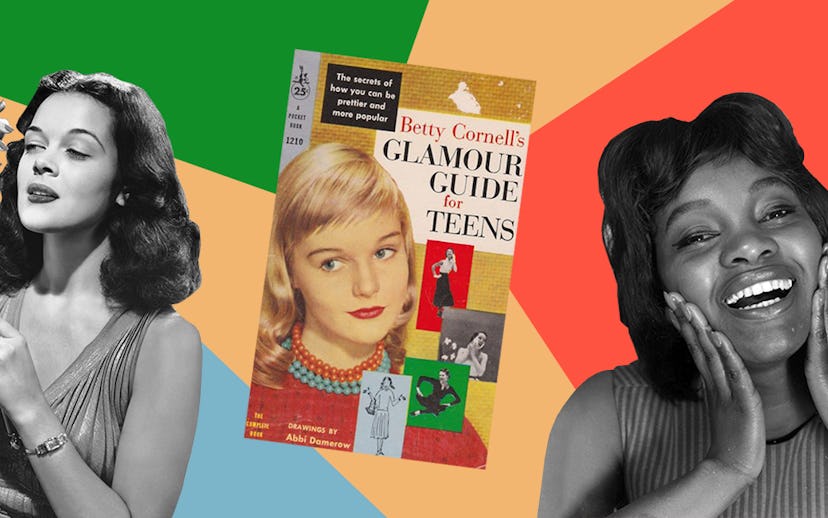

Written in 1951, Betty Cornell's Glamour Guide for Teens promises to give its readers all "the secrets of how you can be prettier and more popular," and the cover features the elegantly tilted head of a TERF-banged blonde gamine, whose eyes look up and off to the side, while the corners of her perfectly painted red lips are lifted upward in the slightest of smiles. She is beautiful—almost certainly prettier than you—and her enigmatic expression is so compelling as to make it impossible to believe that she is not also more popular than you. She is also not Betty Cornell.

Cornell can, though, be found in miniature on the cover, in a series of three photos in which she is preening, one gloved hand on her hip and one on her face; smoothing what is probably cold cream on her cheeks; and sitting, cross-legged, in a full-body leotard, arms akimbo, hands on her knees. But she is more clearly seen on the back of the book, leaning expectantly forward, close-cropped dark hair pinned back, wearing a high-necked, sleeveless white blouse and wrist-length white gloves, a small smile parting her lips, her gaze fixed on someone far off-camera. Beneath the photo is a brief manifesto of the book, Cornell's message to readers: "The purpose of my book is to help you teenagers make the most of yourselves."

More than 60 years after its publication, Cornell's purpose seems to be working; it seems like this book gets rediscovered over and over—and not just by my friends. It was notably the inspiration for Popular: How a Geek in Pearls Discovered the Secret to Self-Confidence, a 2014 book by a teenager named Maya van Wagenen, who was given Cornell's book by her father, and proceeded to follow its dictates in order to, well, become prettier and more popular following a move in eight grade that left her at the bottom of her school's social hierarchy.

Though I haven't read van Wagenen's book, I, too, was given Betty Cornell's Glamour Guide by my father when I was a teenager. He'd found it in our library's giveaway bin, and thought I'd find it funny, just as van Wagenen's father did. That's where the similarities end between our experiences with the Glamour Guide, though, because I did not follow the book's advice. There was no possible way I was going to start slurping consomée or eating cottage cheese or smearing my face with cold cream.

But I still loved reading about all those things. I loved reading Cornell's admonishments to be a good person and not, you know, blackball anyone (I had learned about blackballing from reading about high school sororities in Sweet Valley High). It didn't matter that they had no bearing on how I would conduct my life, this book made it fun—and funny—to imagine following some sort of code of existence. My adolescent life was a chaotic mess, so the neatness of Cornell's unified way of being was a balm. I can see now that the book's allure was something similar to what Abbey Bender recently wrote about in BuzzFeed, about her love of Cosmopolitan covers from the '70s:

As a young woman in the hellish year of 2018, I find these covers surprisingly soothing. I love their distinctive, consistent aesthetic, and the glamour and confidence the models project. There's an aspirational quality to them; they make me want to wear more makeup and lower-cut dresses and be the kind of woman who will happily take the boldly phrased advice of the headlines. Even if it's misplaced, I can't help but feel nostalgia for this era I never got the chance to live through.

And I think that's what I was feeling back in the late-'90s when I first learned about Cornell, whose experience being a young woman was completely alien to my own. Unlike those Cosmo covers, there's no mention of sex, or even much about dating, in the Glamour Guide; and Cornell has this to say about young men: "Do not underestimate a boy's intelligence." But I was pretty sure, even as a young teenager, that it's basically impossible to do that. And, obviously, though Cornell teaches tolerance as being an important part of one's personality, the book is a product of its time, and thus speaks to the experience of a very specific socio-economic segment of white girls in America at the middle of the century. There's little doubt that Cornell's is the America that lots of conservatives think of today when they speak of the nation's greatness.

This is the problem with nostalgia's allure, with any obsession with the good old days; the question always remains: For whom were those days actually good? Were they actually good even for the young women who followed this book's advice? Or did they just make themselves into pretty girls with winning personalities so that they could get married right out of high school, start having children, and still be decades away from a time when they were allowed to have credit cards in their own names?

Or maybe it's not a problem, because maybe that is the real allure here, that we get to dip into this slightly poisonous past and know that its appeal lies not in any earnest celebration of prettiness and popularity, but rather the hypocrisy that is contained within. Maybe what we love is that the book is promoted as a way for young girls to be their best selves, but that there is no real talk of life after high school, so readily is it assumed that marriage is the inevitable outcome of any successful makeover. Maybe what we love is that even though we're supposed to be taking advice from Cornell, an apparent arbiter of young womanhood, she isn't even the young woman seen on the cover. Or maybe why I keep it around, and have carried it from my parent's home to my college dorm to apartment after apartment for all these years, is because I want to be reminded that looking at artifacts from the past doesn't answer the question of "how should a woman be," but rather makes it resolutely clear that there is no answer—there never was, and there never will be. And that's just how it should always be.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.