Entertainment

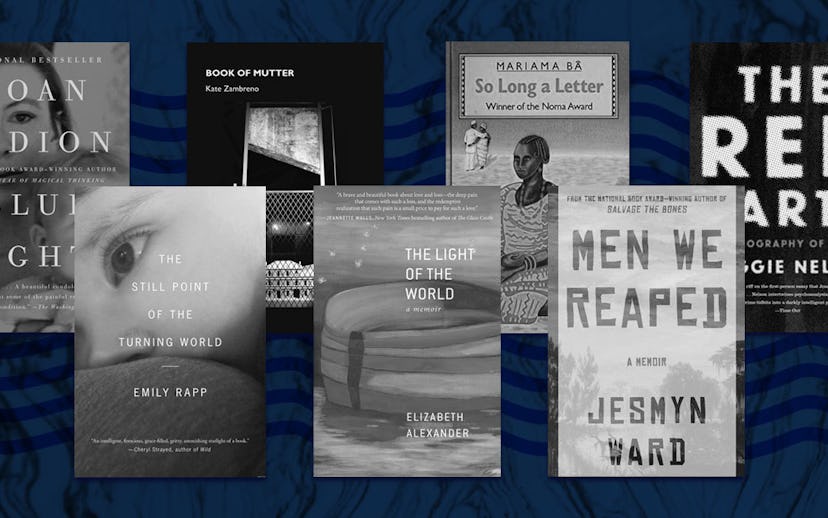

7 Powerful Books By Women That Deal With Death And Grieving

“Writing is how I attempt to repair myself, stitching back former selves, sentences.”

The Fraenkel Gallery recently closed an exhibit by French visual artist Sophie Calle called “My mother, my cat, my father, in that order,” a title that glibly sums up a sequence of deaths in her given and made families. Within the exhibit the artist threads connections to her mother by pulling from her diary. Calle writes:

On December 27, 1986, my mother wrote in

Her diary: ‘My mother died today.’

On March 15, 2006, in turn, I wrote in mine:

‘My mother died today.’

No one will say this about me.

The end.

Just like that intergenerational trauma is collapsed into six sentences whose single repeated phrase echoes the famous opening line of Albert Camus’s L'Étranger: “Aujourd'hui, maman est morte,” spoken by a son who has just learned of his mother’s passing. To this day translators still debate the proper translation of Camus’s sentence. They try to puzzle out meaning from its inflection and syntax in futile attempts to bridge the chasm of meaning that gets lost in the translation of language and thought. A conclusion to that decades-old debate seems unlikely, chiefly because grief has a certain ineffability; it remains both elusive and pervasive within the human experience.

It is often said grief has seven stages: shock, denial, anger, bargaining, guilt, depression, acceptance. But anyone who has ever lost someone, who has experienced a presence becoming an absence, will tell you that these stages are not emotional silos but rather constantly overlapping layers. On this reading list, a collection of very talented women writers attempt to piece together their thoughts about the way death bisected their lives into the moments their loved ones were alive, and the moment they weren’t. Their accounts of reckoning with loss share similarities, like the always-painful confrontation of their own mortality, and the messiness of their recovery timelines, which are dotted with attempts to move through grief which is a fog of time and of feeling.

Book of Mutter by Kate Zambreno

The cover of this book is a photograph of sculptor Louise Bourgeois’s "Cell," an installation where a replica of the artist’s childhood home is enclosed in a wire cage with a guillotine hovering overhead. For Zambreno this image represents the book’s primary objective, severing past from present. Book of Mutter is a project 13 years in the making. The subject is Zambreno’s mother whose death from cancer left her daughter wracked with guilt and grief.

As a writer, Zambreno is hard to pin down, she’s as quick to cite Beckett and Barthes as she is to relay a story about her mother’s gardening journal and the minutiae of suburbia. Her writing, like the act of remembering, is at once collected and feverish, dream-like. It’s free narrative structure is modeled after Bourgeois’s "Cell" project and the ancient Greek method of loci, a technique to enhance one’s memory recall that involves imagining memory as a large house whose rooms we rummage through. Zambreno’s methodical scrapbooking of her memories results in an autobiographical text that elegantly unites the structures of the prose poem and the memoir. Time is fluid. We witness her childhood but are also present in the moment when the very words we are reading are typed. On any given page trenchant critical observations sit next to sentence fragments that end in em dashes which feel like self-conscious hesitation marks, doors to rooms in her mind she isn’t ready to open. “Writing,” Zambreno explains, “is how I attempt to repair myself, stitching back former selves, sentences.” Book of Mutter is an intimate introduction to those selves and a sharp and moving inspection of grief.

The Light of The World by Elizabeth Alexander

This memoir from award-winning poet Elizabeth Alexander tells the story of her marriage to Eritrean immigrant and painter Ficremariam Ghebreyesus who died of cardiac arrest in 2012. The title is taken from a Derek Walcott poem of the same name and though it details the event that made her a widow, Alexander insists the book is as much about having loved her husband as it is about having lost him; it is at its heart a love story.

She and Ficremariam—who she calls by his abbreviated name “Ficre” which means “love” in his native language—fell in love at first sight in a vibrant moment she likens to lightning turning sand into glass. They met in New Haven, Connecticut, in the spring of 1996 while he was a chef at a local restaurant. Alexander notes that while he was alive he was shy about his art work but she makes the smart decision to reprint his artist statement in the book as an opportunity to let him speak. She also litters the book with his most beloved recipes for tomato curry and spicy red lentils.

Over the course of the book it appears she’s wrestling with how best to remember their story and seems to settle on measurement as one answer. Fifteen: the number of Thanksgiving dinners they shared; seven: the number of languages he spoke; two: the amount of children they had; 365: the number of days she kept paying his cell phone bill so she could save his text messages which were his thoughts, which were him. “Perhaps tragedies are only tragedies in the presence of love, which confers meaning to loss,” she writes. It is easy to read love’s presence in this wife’s elegy to her late husband in book form.

The Red Parts: Autobiography of a Trial by Maggie Nelson

In 1969 Nelson’s aunt, Jane Mixer, was murdered in Michigan while attending law school, and the case was never solved. Years later, around the time Nelson is set to release a book about the then-cold case on her aunt’s murder, her family receives a call from a detective who tells them he’s about to reopen the case to make an official arrest. This news throws Nelson and she sets up shop in Michigan to follow the trial proceedings. Nelson’s approach to grief is to arm herself with information about the case, to approach her family’s trauma like a detective.

At the time of the trial in July of 2005, Nelson was teaching at a college, which she used to help her serve as an unofficial investigator in the case—she poured over material in the school’s science library related to DNA evidence and clinical psychology. In between the trial proceedings we hear from Nelson about what it is like for her and her mother to reopen this family wound. This is when Nelson is at her most thoughtful. She interrogates her drive to solve the murder of an aunt she never knew, positing that her interest could stem from her grandfather’s telling slips of the tongue when he would mistakenly call her “Jane” instead of “Maggie.” Nelson also attributes her fascination to a feeling of wanting to correct for what she felt was the “faulty grieving” of her family, whose instinct all her life was to repress this tragic event and with it Jane’s memory. Nelson’s taut and engaging writing make this memoir as much a crime thriller as it is a riveting portrait of one family’s path to healing.

The Still Point of the Turning World by Emily Rapp

This book is about becoming part of an exclusive club no one wants to gain entry to, that of parents who outlive their children. When Rapp’s son Ronan was nine months old he was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease, and his mother recognized it instantly as a death sentence. She would spend the remaining months of Ronan’s life loving him while simultaneously preparing to lose him. This book is an attempt to write her way out of the helplessness the diagnosis forced upon her.

Rapp’s time at Harvard’s Divinity School shines through in the vigorously intellectual way she approaches the question of faith, opening herself up to all philosophy and mythology from Emerson to Buddha to C.S.Lewis. The memoir is a stunning look at maternal devotion that truly comes alive when Rapp unloads her anger. In one passage she takes aim at sympathy cards and their givers, writing, “[they] are about as useless as candy cigarettes—just give me the real thing.” Her emotions are raw and her writing is heartfelt but barbed. The Still Point of the Turning World is a lesson in love. Rapp notes that in the maddeningly brief time she had to be Ronan’s mother she learned the practice of loving and doing so unconditionally.

Men We Reaped: A Memoir by Jesmyn Ward

“I wonder why silence is the sound of our subsumed rage, our accumulated grief,” Ward writes before using her book to break hers. From 2000 to 2004 Ward lost five black men—one of whom was her younger brother—from her hometown of DeLisle, Mississippi. “My ghosts were once people,” she writes, “and I cannot forget that.”

This book returns these men to their flesh. It takes five seemingly unrelated deaths and weaves a story that connects them all through their connection to Ward, and through the socioeconomic conditions that bonded them to their small rural town: their poverty, their blackness, and their fatherlessness. Ward stops every so often to share statistics about the community of the black South and the things tearing it apart like inadequate mental health care and resource-poor and racism-rich schools. She writes with devastating emotional honesty.

Interspersed with these memories is the bullet point version of the story of Ward’s life from young black girl in the American South to first-in-the-family college student at Stanford University to twenty-something aspiring writer in New York. But mostly, Men We Reaped is Ward’s testimonial about bearing witness to the lives of the black men she knew and loved whose individual ghosts haunt her the way they collectively haunt history.

So Long a Letter by Mariama Bâ

This slim novel from Senegalese writer Mariama Bâ is written as a letter from Senegalese school teacher Ramatoulaye to her childhood friend Aissatou. Ramatoulaye’s husband of thirty years, Modou, died from a sudden heart attack. The events of the book take place within her iddat, a mourning period of over four months observed by Muslim widows. Within the letter, which Ramatoulaye dubs “a prop in [her] distress,” are her innermost thoughts about her marriage which are a mix of anger and grief because after ignoring her for most of their union her husband had recently taken a second wife, a practice allowed by custom but that surprised and angered her. Still there is genuine ache in Ramatoulaye’s recollections of their time together. “Like opium, I missed our daily consultations,” she reminisces. “I side-stepped my pain in a refusal to fight it.”

Throughout the letter she touches on the emotional labor of being a co-wife, the constraints placed upon her behavior and dress by tradition, and her small attempts to live her new independent life like finally going to the movies by herself. So Long a Letter is a fascinating look at Senegal’s widow culture and more broadly, how we perform grief for others versus how we experience it internally. We owe this nuance and intimacy to the book’s structure as a letter between friends. In this way, Bâ’s novel makes a strong case for the restorative power of (specifically female) friendship.

Blue Nights by Joan Didion

In her best-selling 2005 memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, Didion reflected on the loss of her husband and sometimes editor John Dunne. Around the time of its publication she suffered another loss, that of their adopted daughter Quintana Roo Dunne, who died from complications from a flu.

In Blue Nights, Didion returns to the subject of loss in a book full of wistful meditations on aging and mortality. We learn about what Didion was like as a new mother and how she helped Quintana prepare for her wedding day among other fragmented memories of her family’s idyllic bicoastal life spent flying between Malibu and Manhattan. But an uncharacteristic gloom weighs heavy over the prose. This isn’t the crisp, breezy, and effortlessly glamorous writing that has come to define Didion. These pages are perfumed with sadness. The blueness referenced in the title is as much a tone of voice as it is a mood. There are no quick quotables or death-provoked realizations, just a pensive woman looking at how loving and losing the two most important people in her life shaped and reshaped her. This is a survival story. It is this emotional nakedness that makes this memoir one of the most intimate literary offerings from one of America’s greatest essayists.