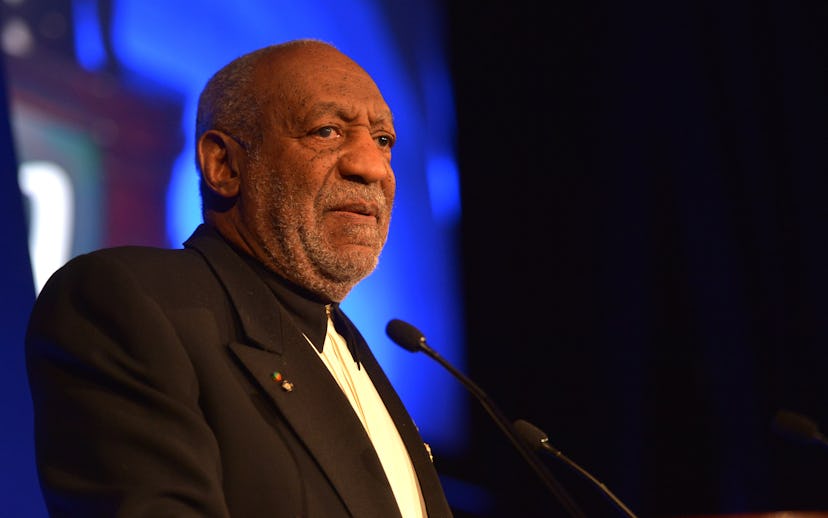

bill cosby’s deposition and why we need to talk about consent

and listen to survivors

In a 10-year-old deposition acquired by the New York Times this month, Bill Cosby testifies to sexually taking advantage of young women through false promises of mentorship, drug use, and emotional manipulation. Yet the comedian has not been formally charged for any cases of sexual assault.

The deposition proves that Cosby, in his own words, has used his influence and power to coerce women into sexual relations; however, even as he describes the interactions, he fails to see the encounters as rape. In an excerpt from the deposition, he describes an evening with Andrea Constand, the woman who, in 2005, claimed that Cosby drugged and molested her thereby causing the deposition to take place. "I walk her out," Cosby said, revealing details about what happened after the encounter. "She does not look angry. She does not say to me, don’t ever do that again. She doesn’t walk out with an attitude of a huff, because I think that I’m a pretty decent reader of people and their emotions in these romantic sexual things, whatever you want to call them." Cosby relied on his own interpretations of drugged women's nonverbal cues to assume that the encounters were consensual while he was sober. (He admitted that he did not take the drugs himself.) An encounter in which one participant cannot or does not give consent is rape, full stop.

So why are we not calling Bill Cosby a rapist?

The deposition reveals Cosby's candor about his sexual exploits, even admitting that he pretended to care about one young woman's late father in order to manipulate her and coerce her into sexual relations. But Cosby, through the dozens of accusations and through his own admittance of drugging women with quaaludes, has not acknowledged his wrongdoing. Though many condemn Cosby's actions, there exists a hestiation about calling the actor a rapist—despite many women expressing details of their nonconsensual assault and the deposition's confirmation of drugs used to alter women's mindsets.

Through Cosby's own confession we know that he has raped over a dozen women—even if he would not use that term to describe the encounters. Yet Bill Cosby remains a free, albeit largely hated man today. President Obama said that he does not have the ability to revoke a Presidential Medal of Honor, a medal Cosby was awarded in 2002. POTUS did not speak further to the Cosby allegations, but said, "If you give a woman—or a man for that matter—without his or her knowledge, a drug, and then have sex with that person without consent, that’s rape." The Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, which is responsible for awarding stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, has refused to remove Cosby's star no matter what. Although some other measures have been taken to purge Cosby from our collective pop culture—like Walt Disney World removing a statue of the comedian and Cosby Show reruns pulled from most networks—we still have a way to go to truly acknowledge the actor's crimes and make him pay for his actions.

The discussion of consent is finally becoming important, with New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo signing a uniform sexual consent policy earlier this month. But there is still much more work needed to be done. Without consent, sexual encounters are rape—and they should be called as such.