Entertainment

Type A(my): An Ode To ‘Brooklyn Nine-Nine’ For Celebrating Ambitious, Perfectionist Women

This is an Amy who’s really amazing

When my husband and I saw Lady Bird, he said, of Tracy Letts’s Larry McPherson, “That’s the kind of dad I’m going to be.”

“No!” I exclaimed. “You can’t be! Because if you’re that dad, then I have to be that mom!”

Lady Bird’s mom loves her intensely, of course, but she’s the bad cop, because she has to be. Every partnership has a bad cop. Everyone can’t all be chill. If everyone is chill, nothing gets done. And so when one partner is fully chill, the other, we’re told and shown, becomes a monster.

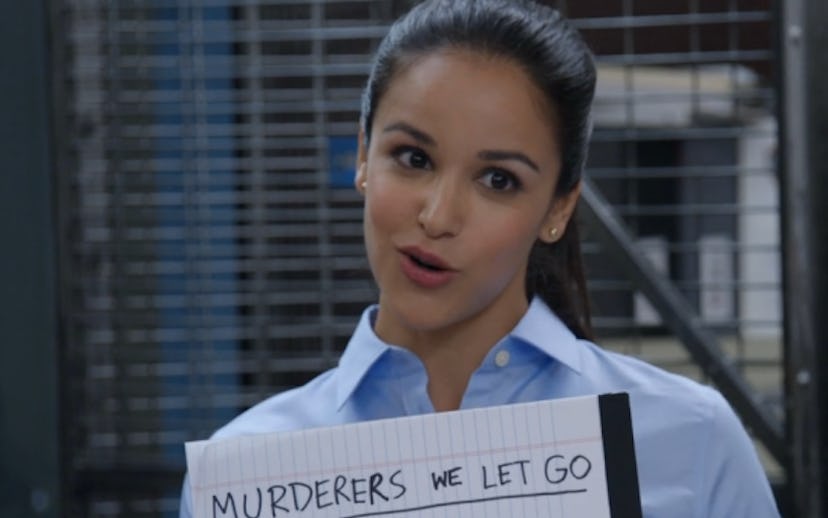

When word came last Thursday afternoon that Brooklyn Nine-Nine had been canceled, my reaction was a kind of panic; I went through all the Kübler-Ross stages, save acceptance, at once. A gasp and, “No! Doesn’t everyone love this show?” bargaining in the hope that another network or streaming service would pick the show up (not so delusional, as the news played out, word came that the show has been given a second life by NBC). And then depression set in, as did a clear sense of what would be lost. It wasn’t just the disappearance of a lovely half hour every week, funny and weird and gentle, surprisingly incisive, too, but also of a character who’d become a touchstone for me: Melissa Fumero’s detective—now sergeant—Amy Santiago. Amy is a controlling, perfection-striving, overachieving Type A woman who not only was never made out to be a monster or a bitch but, also, was honored for who she was, making her a pop culture unicorn.

Like everything about Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Amy’s character has matured and deepened over the show’s five seasons. At first, she was almost purely a trope, an overachieving Goody Two-shoes who sees the precinct’s new captain as a potential mentor toward her own future captainhood. (Though even when she was more one-dimensional, because this show is so damn good, she was teased but never mocked for her quirks.) In the very first scene of the pilot, Jake (Andy Samberg) is charmingly goofing off at the scene of a robbery. Amy is the killjoy who tells him to get it together, who does the thankless work of keeping them on task. Yet Jake is the one who solves it, seemingly pitting cool guy spontaneity against Amy’s by-the-book sensibilities.

From the first episode’s opening scene, Jake and Amy were set up as that familiar trope of a partnership: the uptight, controlling, bossy woman, and the freewheeling, fun-time cool guy man-child. When Jake cracks the case, it’s fully in line with what pop culture has taught us to expect—this woman becomes a shrew, this man knows better than her, and, if she’s lucky, after several scenes or seasons of her scoffing at him, he’ll teach her to loosen up a little.

But Amy can’t help but smirk at Jake’s antics. Not because he’s so charming—though he is—but because underneath his goofiness, he’s as ambitious and devoted a detective as she is. He’s just also a big doofus. (I hope an ambitious, doofy guy somewhere is writing his paean to Jake.) Now, years later, they’re engaged. Their wedding planning has been a running thread of the show’s latest season, a clever way to maintain tension, the couple against the world instead of each other. And they are on the same team—remarkably so. In fact, it’s the wedding arc—a narrative treatment almost always designed to mock a bride’s intense enthusiasm—that made me realize how amazing and rare the show’s treatment of Amy is.

In an episode earlier this season, “The Venue,” Amy and Jake walk into the Nine-Nine side-by-side, Amy clutching a white binder in her arms, to announce they’ve found a wedding venue and to tell their whole workplace to save the date. Boyle says, “So, tell us about the venue!”

Amy demurs for a second, “Oh, well, there’s not much to tell...” She’s being coy—the woman is a planning machine—and she can’t hold it in: “... other than it’s a GORGEOUS MANSION.” She is so intense. We’re ready for her to steamroll us.

But then, Jake chimes in an echo: “Big ole house!” And something magical happens. Every expectation falls away: Women plan weddings, men are dragged along for the ride. Control freaks dominate—emasculate—their partners. This way of being is unloveable.

Nope. Instead, a beautiful call-and-response kicks in, Jake playing the hype man:

"It’s a GORGEOUS MANSION...” (“Big ole house!”) “...with a professional kitchen...” (“Chop chop, y’all!”) “...a private library for the ceremony...” (“My girl loves books!”) “...seven bathrooms!...” (“No lines, ladies!”) “... and an outdoor reception area!"

Jake holds his hand to his ear like a DJ. “Uh, can I get a gazebo!” He scratches an imaginary turntable. “The point is, these nuptials are going to be toit.”

“Speaking of toit nups,” Amy says, slipping out of ebullience and into efficient, businesslike patter, “we better get going because we don’t have a lot of time and we have to meet with 17 wedding vendors.”

“A jam-packed schedule that could only be achieved by a Type A personalityyyyy!” he announces to the room, still stuck in proclamatory mode. And then they swoop out and off to their plans.

Jake was along for the ride. This clearly isn’t his passion, but Amy is a creature of pure enthusiasm and intensity, and he’s been sucked in. And happily, too. His girl loves books, and he is psyched as hell that she’s going to get married surrounded by them. I love that this happened—and I hate that it struck me as so amazing.

The bossy bitches in our culture are legion, but she’s always the bad cop to her boyfriend’s or husband’s good: the rule-setter, the line-drawer, the fun-killer. Sometimes she’s the butt of the joke, sometimes, as in Lady Bird, she’s the heart of the pathos. But only Amy gets to have her Type A cake and eat it, too.

Writing that, I second guess myself. There are movies and TV shows I haven’t seen. But my other Type A TV touchstone is Leslie Knope: intense and ambitious, a fellow devotee of three-ring binders and color-coded organizational systems. Those qualities were celebrated and gently gibed, as Amy’s are. But Pawnee’s surreality made Leslie more of an icon than a human being sometimes. And she married Ben Wyatt, a fellow high-strung Type A. There was so much beauty in him devoting his ambition to the service of hers, but they had a different path, never bound by this cliche’s particular misogyny.

It’s in Amy’s partnership with another easy stereotype, the goofy man-child, that her character becomes such a beacon and a gift. She has to sink fully into the trope, to tempt its every cliche, in order to break it open.

At dinner Thursday night, I brought my husband the news that Brooklyn Nine-Nine was being canceled. And then I told him I wanted to write this essay, about how amazing it is that the show lets Amy be the way she is and be loved for it. He asked, “Is it because they’re us?”

“No, I don’t think so. I identify with Amy, but I don’t think you’re a Jake.”

“I do,” he said. Of course, he does, I realized. And I realized, too, that I didn’t just love the show for the hopeful way I saw myself mirrored in Amy, but for the hopeful way I saw Amy and Jake together mirroring us.

That was me Amy-ing, again, I realized, the blinders against the periphery, eye too tightly on the prize, unable to see things for what they are at first, even if I get there eventually. But this doesn’t make me someone who needs to be fixed or told to chill out, just like Amy doesn’t need Jake to chill her out, either. She just needs him to love her. And it’s a beautiful gift to all of us that, for five seasons, Brooklyn Nine-Nine has let him. And by depicting an imperfectly perfect person like Amy with so much love, the show has allowed us to love her, as she is, as so many of us are, too.