Entertainment

Chris Abbott On His Grueling, Star-Making Performance in ‘James White’

the former ‘girls’ star comes into his own

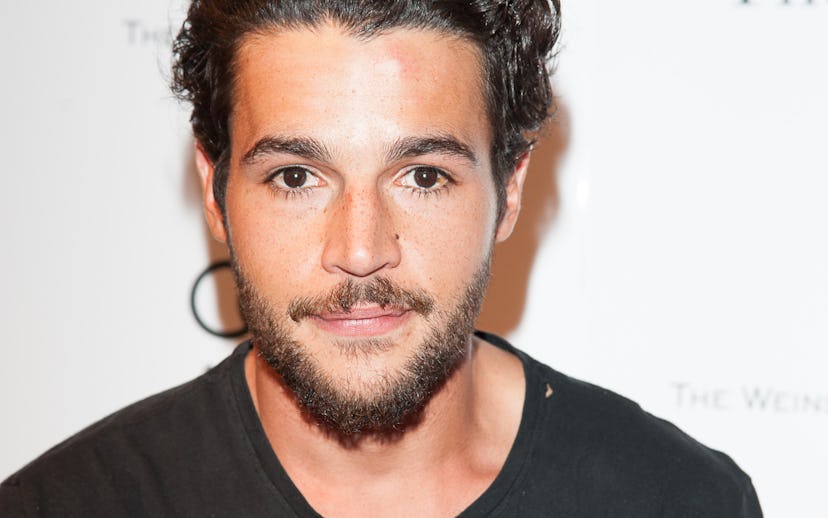

“I never expect awards when I get involved in a project, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t care about it, because it’s nice to be recognized,” a bearded, steely eyed Christopher Abbott tells me when we meet at the Toronto International Film Festival, where he's promoting his buzzy drama, James White. The movie, which made a splash at Sundance earlier this year, charts the semi-autobiographical story of a fairly reckless and hedonistic New Yorker who’s forced to get his act together when he becomes the designated caretaker for his mother (Cynthia Nixon) following her cancer diagnosis. It's a project that had been percolating in the mind of first-time director Josh Mond ever since his own mother succumbed to cancer some five years ago, and one that has been earning Abbott awards attention for the first time in his career.

“I definitely don’t take it for granted,” he says of the near unanimous praise for his performance in the prizewinning Sundance drama (Abbott was just nominated for an Independent Spirit Award). “I understand this is a special scenario: It’s a movie I made with some really close friends; a film I had a lot invested in. Not just as an actor, but emotionally, and as a friend. So, it’s extremely meaningful to me. It’s something I’ll remember for the rest of my life.”

To its credit, James White doesn’t follow any of the tearjerker tropes we’ve come to expect from Hollywood of late. When an audience member at the TIFF Q&A gushed about it being a fine “cancer film,” Nixon kindly set the record straight. “It's unlike most cancer films, as it has more in common with novels about young men coming of age and with antiheroes—this person who is clearly our protagonist, we watch him make mistake after mistake after mistake, and yet we keep rooting for him because there's something about that person we find desperately compelling.”

Mond had bonded with Abbott during the shoot of the indie hit, Martha Marcy May Marlene, which was directed by his producing partner Sean Durkin, who together with Antonio Campos, make up Borderline Films. Abbott felt he had a “family duty” to play the part.

“They’ve all become such dear friends of mine now,” says Abbott. “I was even a groomsman at one of their weddings… It just felt as though I had to do [James White], acting aside, because Josh and I have history. Josh uses the word family a lot—in regards to his partners, to the people he likes to work with—and he stays true to that. Because we’re family in that way, I always felt I was going to do it.”

In person, Abbott exudes the same kind of slow-burning intensity that defines James, which is precisely what makes him so compelling to watch onscreen. A cursory survey of his inked arms reveals the importance he accords to notions of family—both the kind you’re born into and the kind you build as you come into your own. “The flower is for my grandmother,” he explains. “The A is for her name Angelina, and the flower is a rose, because she was born in a town called Rosa in Italy.” He’s also got the words “left out winter” etched onto his right forearm—a line from a play written by his good friend Lucy Thurber, whose calligraphy was faithfully reproduced. And the fish hook? “That one is not as ‘deep meaning’,” he cautions jokingly. “That was the first tattoo I ever got. I did it with a friend at her apartment—Jemima Kirke, who was also on Girls—she did it with a needle wrapped around a pencil, an after-we-had-a-few-drinks kind of thing. So that was more on a whim, but I guess I do like fishing!”

He tells me about his upbringing in Connecticut and his former landscape-architect aspirations, and what transpires is how quickly he sought out people who shared his hunger for the arts, after experiencing his eureka moment doing theater in community college. “Growing up, the idea of one day becoming an actor was not in my wheelhouse at all,” he says. “Movies and film – all of that felt extremely far away. So in the early stages, when I first moved to New York, I definitely drew inspiration from people who encouraged me to pursue this, especially my teachers at HB Studio.”

In meaty, indie roles from Martha and All That I Am, all the way to James White, Abbott has steered clear of the expected pretty-boy antics, embracing instead darker characters that come with considerable baggage, in the form of vaguely dangerous, under-the-surface energies and bottled-up emotions. “It’s more compelling to me than a stereotypical angsty character who’s just always acting out,” Abbott answers, when I ask what draws him to less outwardly expressive characters. “It could become masturbatory in that way. I’m not saying it doesn’t work; sometimes, given the material, it’s earned and that’s okay. But with this part specifically, I think we really needed to play with the levels of that—somebody who keeps their emotions bottled up.”

For Abbott, acting is about calibrating moments of heightened emotions with long stretches of restraint—a balancing act that must feel true to life. Watching James White, the audience vicariously experiences James’s claustrophobia in an anonymous urban jungle as well as his self-imposed pressure to keep a lid on all feelings until they just sloppily spill over. Our response shifts from wanting to berate the self-involved man-child, to hugging the twentysomething-in-turmoil and tell him everything’s gonna be okay. That speaks volumes about Abbott’s beautifully measured performance. “I feel like that’s what it’s like in life more often,” he says, when asked about the (pent-up) performances that resonate most strongly with him. “In documentaries, you watch people being interviewed about something that’s very personal to them, and they do every bit they can to smile through it and not show their emotions. No one wants to show their emotions, because then they’re being vulnerable. I find it so much more moving to see that happen in people that I then want to try and do that.” Mission accomplished.