Entertainment

A History Of Drake’s Complicated Relationship With Women

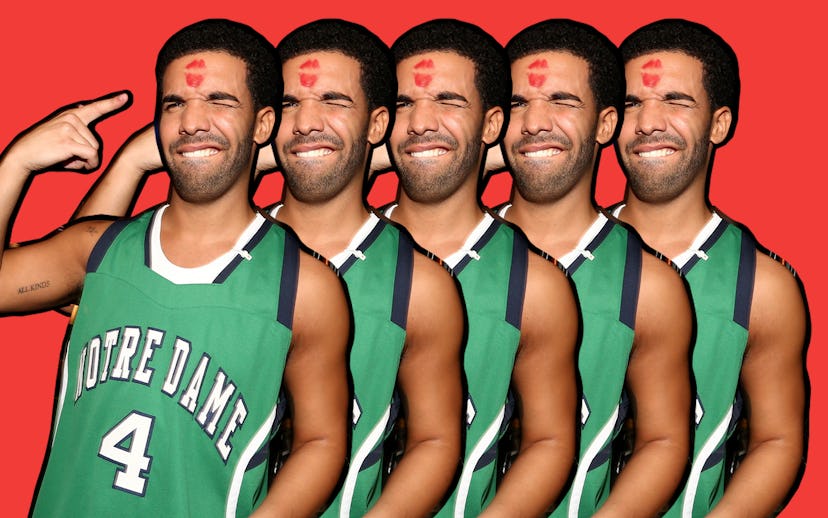

The heartbreak kid

While he’s spent plenty of time putting on for Toronto and roasting Meek Mill like an ant under a magnifying glass, what’s brought Drake a tremendous amount of fame are his songs about love. Well, maybe "love" isn't the right word. Maybe they're better called his "women songs," occasionally profound, often insightful, and always confessional to a fault. While Drake can fall back on prototypical rapper bluster and bravado, throughout his career he has, for better or worse, made a concerted effort to find a place in his lyrics for every woman he’s ever passed on the street or thrown money at in a strip club.

Now seven albums/mixtapes/playlists into his career, there’s a pretty staggering amount of Drake's work to parse, plenty of it dealing with women. And this raises the question, has Drake’s attitude about women changed over the years?

What follows is an album-by-album breakdown of the women Aubrey Graham has discussed and how he’s talked about them. Be warned: For those with especially low Drake tolerance, the following dosage may prove fatal.

Pt. I: Heartbreak Drake

With So Far Gone, his career-changing 2009 mixtape, the Drake ethos that we’ve now come to expect was still only being formed. As such, the psychographic of women he lusted over was more in line with your run-of-the-mill mid-2000s rapper. On “Houstatlantavegas” he waxes poetic about a jet-setting stripper, and on “November 18th,” he’s flexing about a Houstonian girl in one of his earliest instances of cribbing from a specific regional style (in this case chopped-and-screwed).

On the former, you can see the outline of who Drake would become later in his career coming into focus, like the montage in a superhero movie where the hero goes through all the different iterations of their outfit before finally landing on the right one. One moment he raps, “If she wants it, she’ll get it on her own,” praising this woman's independence and hustle, but then on the next verse Drake is taking advantage of her in a compromising situation:“You go get fucked up and we just show up at your rescue/ Carry you inside, get you some water and undress you.”

“Best I Ever Had,” the single that launched Drake into the mainstream consciousness, is not especially illuminating about the kind of woman that Drake was fawning over at the time, though in an interview with Toronto’s FLOW 93.5, he claimed that the song was about an ex, Nebby, who “represented everything about the city that I loved.” That insight is perhaps the defining connective thread of the women Drake pines over on So Far Gone (and, to a lesser extent, throughout the rest of his career): geography. The young Drizzy, not yet jaded with the rapper lifestyle or ready to go full late-night Tumblr confessional, saw women as entry points to locations that signified his emergence as an artist.

Pt. II: The Drake Life Cycle Takes Shape

Thank Me Later begins filling in the outline created on So Far Gone, while also establishing the “good girl gone bad” heuristic that has been adopted by a concerningly large number of male pop artists. The purest example of this is likely “Karaoke,” a spectral ballad with Drake crooning in fledgling falsetto about an ex who moved to Atlanta, a city Drake deems to be fraught with temptations. “I hope that you don't get known for nothing crazy/ 'Cause no man ever wants to hear those stories bout his lady,” he raps on the final verse. After boasting about the women who flock to him for his behavior on So Far Gone, Drake is now reckoning with the fact that his lifestyle is repellent to some (“I was only trying to get ahead/ But the spotlight makes you nervous,” he sings on the outro).

Though Drake has been linked incessantly to other celebrities, his on-record persona shows a clear preference for plucking women from obscurity and elevating them to his level. He sums it up pretty well with a “Go Cinderella, go Cinderella” chant on the grating “Fancy,” as well as in “Shut it Down,” where his muse is a “student working weekends in the city.” (For the record, “Shut It Down” is still one of Drake’s most enjoyable love songs, and proof that he should’ve kept working with The-Dream.)

If “Shut It Down” and “Fancy” are about the rising action of a Drake romance, “Karaoke” and “Find Your Love” are the falling action and epilogue, respectively. The latter, originally written for Rihanna, is essentially a weary, heartbroken Drake daring himself to be let down once more.

Here, the life cycle of Drake’s obsession starts to become clear: Drizzy finds a woman—often one he sees as underachieving based on her appearance or intelligence or some other factor—plucks her from obscurity and brings her into his world, only for it to overwhelm and push her away. She moves on and switches zip codes, leaving Drake to scroll through old texts and new Instagram posts, feeling both wronged and protective.

“I’ve been through this s— so many times that if I go through his again,” he told Entertainment Weekly about “Find Your Love” back in 2010. “I better find your love. You better be that one. Because if not, I don’t know what type of guy I’m going to turn into.”

On the very first single from his next album, we got a glimpse into exactly what type of guy years spent chasing women incompatible with his lifestyle would turn him into.

Pt. III: Marvin’s Room And Beyond

It’s rare when an artist does something that leans so heavily into what many of their detractors have criticized them for, but “Marvin’s Room” is Drake doubling down on self-effacing honesty, his love-hate relationship with the rapper lifestyle, and his lust for the one that got away. In this case, the one that got away was alleged ex-girlfriend Ericka Lee, whose voice was used on the track asking Drake, “Are you drunk right now?” and who settled with the rapper out of court after seeking a co-writer credit.

Though undeniably infectious, “Marvin’s Room” is profoundly bitter, it’s a pure projection of Drake’s id and, after flexing on So Far Gone and Thank Me Later, signals a shift toward complete rejection of the women who cling to him for his fame (“I don't think I'm conscious of makin' monsters/ Outta the women I sponsor 'til it all goes bad”). On one level, some of this is simply the marketing savvy of Drake—when every other MC out there is boasting about the women who flock to them because they’re rappers, it’s pretty logical to go the other way. While every other rapper out there is talking about how they could easily steal your girlfriend, Drake is the one who resents you and your stable life for taking her away from him, as he makes abundantly clear on the “Marvin’s Room” hook.

As an album, Take Care is not only Drake’s most sonically cohesive, but it’s also Drake at the most compelling moment of his career; he’s made it to the top and finally has a moment to reflect on whether he even likes it up there. From a romantic standpoint, much of Take Care takes a sledgehammer to the female archetypes Drake had spent the early years of his career coveting, only to build them back up on the album’s more vulnerable moments. He renounces strippers (“And I thought I found the girl of my dreams at a strip club/ Fuck it, I was wrong though” on “Over My Dead Body”), and instead of lusting after the women that left him, now casts them as fuming over his success and pop culture omnipotence on “Shot For Me.” (“First I made you who you are and then I made it/ And you're wasted with your latest/ Yeah, I'm the reason why you always getting faded”).

Drake returns to the strip club on “The Real Her,” a kind of spiritual sequel to “Houstatlantavegas,” only now his motives aren’t to find someone to shower with luxury, but rather to find a kindred spirit with whom he can be himself: “They keep telling me don't save you, if I ignore all that advice/ Then something isn't right, then who will I complain to?”

So three projects into his career Drake has enough of a past to adjust his heuristic, though he’s still young and green enough that he’s still falling into his old ways.

Pt. IV: “What qualities was I looking for before?”

Nothing Was the Same may be the most enlightening peek into Drake’s romantic psyche.

While Drake had worked with Nicki and Rihanna prior to NWTS, his Jhene Aiko collaboration, “From Time,” is unique because it’s the first time it has felt like a female collaborator has been allowed to poke directly at his flaws, or at least those of his persona. “I love me, I love me enough for the both of us/ That's why you trust me, I know you been through more than most of us,” she sings on the hook, laying his insecurities on the table while also addressing the troubled past Drake has been delving heavily into since Take Care. Drake, to his credit, seems to welcome the bluntness, which at least seems deserved given how brazenly he’s called out women on record before. “I needed to hear that shit, I hate when you're submissive/ Passive aggressive when we're texting, I feel the distance,” he responds.

“Own It” starts off empowering, albeit mind-numbingly repetitive, but turns spiteful by the second verse. “My ex-girl been searchin' for a ‘sorry’/ Couple bitches tryna have me on the Maury,” he raps, before wondering why the girl in question didn’t have his back and chiding her for her past.

“Hold On We’re Going Home” is another vintage, good girl gone bad Drake track (“'Cause you're a good girl and you know it/ You act so different around me”). It’s still quite catchy if you can look past how paternalistic it is, which is even more glaring now than it was back in 2013.

Pt. V: *cue eye roll*

If You’re Reading This It’s Too Late, arguably Drake’s leanest and most focused effort, is pretty free of these sorts of musings. Most of the tracks are caustic tales of how his success has incited widespread jealousy and brought detractors out of the woodwork (“Energy,” “10 Bands”). Occasionally the braggadocio recalls earlier Drake trappings; on “Legend,” he’s playing house with a stripper (“Got a girl, she from the South/ Used to work, used to dance in Texas, now she clean the house”), on “Madonna,” he’s offering his coaching services to a girl who “could be as big as Madonna,” seeing potential in her she apparently did not see in herself. He doesn’t specify exactly what he means by potential, but given his history, it’s safe to say that his plan roughly involves taking her from being a stripper and showing her the non-stripper ways of the world (cue eye roll).

On the Travis Scott collaboration “Company,” he offers some insight; at this point, he just wants a woman to distract him from the fears associated with the heights he’s reached (“I need you to take my mind off being in my prime”).

“Jungle” is easily the most instructive track on If You’re Reading This in terms of Drake’s headspace with relation to women. He’s having trouble reconciling what he perceives as his flaws with how his partner sees them (“The things I can’t change are the reasons you love me”). He’s wise enough to know he can’t involve himself long-term now (“Still finding myself let alone a soul mate I’m just saying”) and wishes that the girl would ignore the gossip and her friends and just see Drake for Drake (“Fuck what they talking about on your timeline/That’s cutting all into my time with you”), even though her love of Drake is what’s causing the problems in the first place.

Pt. VI: “I think we should rule out commitment for now”

Views is both Drake’s most successful and probably least personally compelling album, and that means that there isn’t a ton to glean here, particularly since Drake’s newfound fascination with dancehall and Jamaican patois leads him to take on a persona that feels only vaguely related to the Drake he’s put forth before. He takes the theme of wanting someone who’ll be assertive and occasionally dominating on “Controlla,” but it feels gimmicky (“I think I'd lie for you/ I think I'd die for you).

“One Dance” is similarly comical. Drake wants commitment and to feel appreciated (“You know you gotta stick by me/ Soon as you see the text, reply me”), but the song itself is all about proving Drake’s dancehall bona fides, and guests Wizkid and Kyla are given plenty of air time. The girl in question is clearly from Toronto, fitting given that the album was originally titled Views from the 6 and he spends much of the album musing on the influence of his hometown.

Occasionally though, he lets loose with some nasty, controlling lines on tracks like “Hotline Bling” and “Too Good.”

“Hotline Bling” feels like kin to “Karaoke,” though with a more vindictive and frankly misogynistic bent to it. It’s Drake at his most paternal (“'Cause ever since I left the city/ You started wearing less and goin' out more/ Glasses of Champagne out on the dance floor/ Hangin' with some girls I've never seen before”), chiding a girl for moving on from him and wondering if she’s with another man (“Wonder if you're rollin' up a backwoods for someone else/ Doing things I taught you, gettin' nasty for someone else/ You don't need no one else”). Its absurd video lends comic levity, which is unfortunate because a lot of Drake’s worst tendencies are on display here.

That trend is continued on the Rihanna duet “Too Good,” which feels like the sequel to “Take Care” if everything possible had gone wrong in the aftermath. Smartly, Rihanna is given room to act as Drake’s foil and point out his flaws, because the lyrics (“I'm too good to you/I'm way too good to you/ You take my love for granted/ I just don't understand it”) would be pretty unpalatable without a female perspective to counterbalance.

Pt. VII: Get it together

Oscillating between tough guy grime and a kind of dancehall/Afrobeat-lite blend, More Life doesn’t have the same breadth of tracks to examine, but those that are present on the record do show a sliver of growth, albeit his insistence on experimenting with different deliveries and styles does cause some regression. They’re also steeped in the celebrity relationships that he’s become increasingly known for as he’s ascended to global superstar status.

On “Passionfruit,” he’s watching a long-distance relationship crumble, the same kind of situation that would have inspired an overly earnest track like “Karaoke” or a bitter song like “Marvin’s Room” in the past. There’s still an air of "Drake knows best" haughtiness, but it’s couched in recognition that his past mistakes may well doom this relationship. “Hard at buildin' trust from a distance/ I think we should rule out commitment for now/ 'Cause we're fallin' apart,” he sings on the second verse.

“Get It Together,” Drake’s collaboration with rising U.K. singer Jorja Smith, is fascinating because it’s one of only a few occasions where the object of Drake’s affection is given as much or more time to explain her vantage point in comparison to Drizzy himself (“From Time” is similar in this regard). The criticisms levied by Smith feel particularly incisive, even though she obviously isn’t in a relationship with Drake and her verses are actually covers of a 2010 Black Coffee song.

Still, she cuts deep with lines like, “You know, we don't have to be dramatic/ Just romantic,” and “When you're working late/ When you're out of town/ Tell me how much you need this,” while Drake is relegated to backup hook duties. “You need me to get that shit together/ So we can get together,” he admits, taking ownership for his spotty past.

“Nothings Into Somethings” is perhaps the closest Drake has ever come to replicating “Marvin’s Room.” It hits a similar confrontational, confessional nexus. The track has been interpreted as a commentary on the engagement of Serena Williams, a rumored flame, to Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian. While Drizzy is certainly blunt about his feelings (“Least, do I get an invitation or something?/ Ask about that, you would say it was nothing/ But here's another nothing that you made into something”), he is showing some growth and restraint, although it’s hard to blame Serena (or whomever the song is about) for not wanting Drake at the wedding.

“Teenage Fever” tellingly samples J.Lo, who the rapper dated for a couple months and staged an elaborate fake prom for that would put your favorite ‘80s romance movie ending to shame. The track is bifurcated, half about the death of one relationship, perhaps with J.Lo (“Your heart is hard to carry after dark/ You're to blame for what we could have been”), and half about a new relationship with a girl he met at the club (“This shit feels like teenage fever/ I'm not scared of it, she ain't either”).

On “Blem,” a particularly candid track from More Life about taking a girl from her “wasteman” ex and showing her his new tropical lifestyle, he remarks “'Cause I know what I like/ I know how I wanna live my life.” The latter may be true, but parsing through his lyrics, it’s hard to say the same about the former.

Epilogue:

So has Drake’s relationship with women changed over the past few years? Yes, but then it changes back again; if anything Drake has only grown more erratic in how he deals with romance in his music. Where young, naïve Drake was earnest and wistful, the version of himself he portrays on Views and More Life balances moments of extreme clarity and maturity with heavy-handed demands for appreciation that feel like products of middle child syndrome.

Perhaps this is simply Drake leaning into who we all expect him to be, essentially embracing the meme, but it’s also concerning. Just like Drake is stronger when he flips dancehall than when he tries to mimic grime, he’s a far more compelling artist when he’s assessing his own flaws and showing maturity than when he’s falling back on his bitterness. It’s tough to determine exactly what the next chapter of Drake’s career will read like, in terms of how he talks about the women in his life, but if his previous efforts give any indication, he’s probably on the hunt for another woman to save, only to watch her leave him for someone he thinks he’s better than.