Entertainment

This Novel About The Jim Crow South Is An Essential Read For Right Now

“I, like many white Americans, was probably living in the dark”

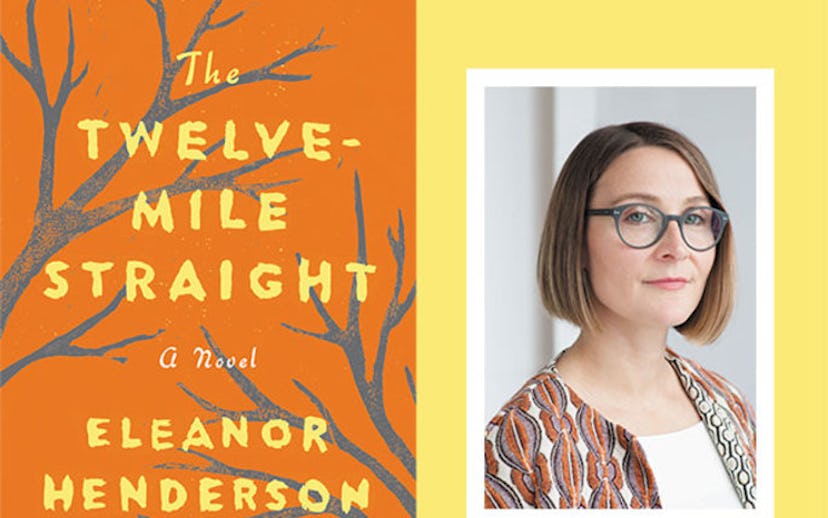

In 1930, in a small town in the fictional Cotton County, Georgia, a young, unwed mother gives birth to twins, a boy and a girl, one black and one white. This is the catalyst for Eleanor Henderson's affecting, profound second novel, The Twelve-Mile Straight, and it launches a series of violent, catastrophic events that speak volumes about the way our society has historically handled issues of class, race, gender, and oppression. The narrative skips back and forth in time, in order to give readers a better understanding of the events that led up to the birth of the "Gemini twins," and in doing so, offers readers a rich, comprehensive portrait of the powerful forces at work in the Jim Crow South, ones that worked to intimidate, oppress, and silence black Americans. Though undoubtedly historical fiction—and Henderson does an incredible job at getting the details of this time period and setting the picture—this story of Elma Jessup, the white sharecropper's daughter who gives birth to the twins; her father, Juke, who has complicated reasons for wanting to punish the man accused of fathering one of the children; Nan, the young, motherless, mute black girl, who lives with the Jessups, almost as a sister to Elma; and Freddie, the town scion who runs away after enacting a vile form of "justice," among many others, resonates deeply in our current political climate, touching as it does on the gross inequalities that still exist in our society today.

Below, I talk with Henderson about the process of writing this epic novel, what it was like to find the voices of some of these characters, and how this book is a portrait of the "failure of white progressivism."

How long was this story in your head? And then how long had you been working on it before it got to the point where it was publishable?

It was kind of rattling around my head in an unformed form for a long time. I remember sort of sitting down and writing page one—probably a pretty similar sentence actually to the one that’s the first sentence in the book—January 2011. So before my first book [Ten Thousand Saints] came out. For a long time, I’d really wanted to set a book in Georgia. I grew up reading Southern fiction, and it really was sort of my first love, especially when I was falling in love with short stories. And my father is from Georgia, and I sort of felt like I might have a Southern book in me. And then, I also was intrigued by this story idea about twins, when I came across this phenomenon of separate paternity—heteropaternal superfecundation, if you want to get fancy. [laughs]

Definitely, I always want to get fancy!

I had this idea that it would be really interesting to follow the story of twins who are actually just half siblings, who are supposed to look more like each other than anybody else, or be more like each other than anybody else, but they actually might be quite different. So the sort of appearance of alikeness versus the actual experience of living with a sibling who’s quite different. And so I thought that would be where the story would take me, but it took me months, if not a year or so, to realize that those two stories might be the same story. That the story about siblings who were different might be pretty powerful in the Jim Crow South, in particular, a place that might be really intolerant of those differences. So it was at least a year before I kind of fit those two stories into each other. And that’s pretty common for me in terms of process—that I’ll have these two stories that I’m kind of stuck on, and then I’ll understand that they want to speak to each other, and once I can get them in conversation, then I feel like the story begins to tell itself a little bit more easily.

But I still struggled once I found my way into this story. It was probably a couple of years, that I worked on the first hundred or so pages of a draft that didn’t work. And one of the reasons why it didn’t work was because I was attempting to tell this story through a kind of side door, through Nan’s voice. And I thought that I might be able to tell the story of the corruption of this white sharecropping family through Nan’s eyes and through her voice, with the idea that she could see this family more clearly than anybody else. She’s this character who’s mute, but I wanted to sort of give her this voice, and ultimately it didn’t work—I luckily had a friend who really was honest with me about really feeling toyed with as a reader, sort of feeling like it was a device to her. And it was. I think one of the reasons why it didn’t work, but also why I was nervous about attempting a more legitimate omniscient narrator, is because I was really nervous about adopting a voice for Nan. And I was eventually, I think, able to sort of get through some of those obstacles and make them the material of the story. But that was one of my main struggles early on.

I wanted to know how you settled on the omniscient narrator voice; one of the things that I really marveled at is just how wildly disparate the experiences of each of these people are, and how complicated it would be to jump back and forth between voices.

Well, the third-person omniscient narrator and the large cast of characters—I was pretty comfortable with that, coming out of Ten Thousand Saint. In part, I wanted to challenge myself to write in the first person, which is really highly uncomfortable for me, and so I felt a little bit defeated in returning to what I felt was a strength that I could fall back on. But I realized that this was a kind of story that needed that even hand. In a story about inequality, it was important that all the characters had equal access to their own voices and that I had equal access to them, or at least a constructed narrator did. And I think it was important ultimately for there to be that deep interior access into each character, in part because they don’t understand each other fully, even when they attempt to really earnestly. Or even when they attempt to speak for each other—Elma intending to speak for Nan, in particular—she can’t do that, so it was important for me to provide that interior access for Nan. But also so that the language of the narrator was able to absorb all of their different voices, and so that it had that quality of what I hope is “shareable language,” to use Toni Morrison’s term. But that it also was limited, that it also takes on the sort of biases of the community, and that it doesn’t know everything, and that some of the dignity is reserved for the characters.

Which was the most difficult character to inhabit? And whose experience was the easiest?

Well, you know, Nan was really a hard hoop to jump through or nut to crack, whatever stupid metaphor you want to use. But when I sat down and thought, early in the process when I thought actually what words would come out of her mouth, I totally drew a blank. I thought, How can I give this character a voice? It seemed like a violence to deny her a voice and it seemed like an equal violence to pretend that I knew how she would speak in that world—as a white writer, as a writer that’s not from the South, at least not from the Deep South. I was really intimidated by that, and I wanted to tread really carefully. I think that treading too carefully, at least in part, it led to this choice of denying her a voice. Like, what would that look like for this character really not to have a voice in a way that she didn’t have much of one, although she did have some power as a midwife and in other ways. And so the kind of nervousness with which I approached adopting this young black girl’s voice kind of transferred onto Elma, who isn’t very conscious of the dangers of speaking for Nan—she does so with love but also with some limitations, and so I kind of pushed my anxieties in that way. So Nan was really difficult, and then once I kind of became comfortable, I was more comfortable speaking through the voices of the characters in the book.

Elma was probably... her experiences as a young white woman are closer to mine than to anyone else’s in the book, and so she was sort of the consciousness that I felt most comfortable returning to.

I found Elma to be so fascinating because of how unflinching you were in portraying what her weaknesses were and what her good intentions were, and how they weren’t enough. There was one part where Nan is observing her and just realizes that Elma is working so hard to protect her father because it was just essentially a way of protecting herself. And it drives the point home so well, of what the problem is in something that obviously is part of our larger cultural conversation today, of the way that even well-intentioned people who benefit from white supremacy, who probably don’t even think that they are because they’re individually poor, are still invested in preserving this horrific status quo.

When I first started writing the book, I didn’t totally get what I was doing or what I was trying to do, and then Megan Lynch was like, “Oh, this is a book about the failure of white progressivism,” and I was like, “Oh yeah, totally.” And so it probably took up a little more consciously after beginning to work with her. I’d written the first 200 pages without her guidance, and it became really important to look at the role of the white woman in particular, who is suffering at the hands of her father and the patriarchal society that she is growing up in, but at the same time she’s very much carrying on the traditions of the father in many ways.

There is no "good white person" in this book, no uncomplicated hero in that community. You kind of read it hoping that at the end they'll find some utopia, but you also know it won't exist because it doesn't in real life. While you were writing this, did you just stop occasionally and think, Wow this is a fucked-up country.

Yeah, on every page. It was a pretty dreary book to write. I mean, I loved visiting this world because it was safe for me, relatively speaking, to do that. And learning about this world and really sort of confronting some dark truths about our own world in it, but it was definitely dreary, and as I was writing it, I was just sort of asking myself, “Is there any way this could’ve been a lighter book?” I was reading James McBride’s The Good Lord Bird, which I love—it’s so funny and so light, and it’s about slavery and murder and everything else—but I’m not sure that this book could’ve been anything but as heavy and dark as it is.

What was the researching process for this like?

It began with my dad. I grew up hearing stories about growing up on the farm. His parents were sharecroppers during the Great Depression in addition to pulling a number of other jobs, and so I always was really intrigued by what seemed like a very distant life. And so I asked him questions. Like, “How did you brush your teeth dad? I need my characters to brush their teeth, what’s that look like?” And so that kind of research was, for me, the most rewarding because it was about really getting a window into a life that had seemed really distant, and it was a real gift.

In terms of the more traditional research, that looked like what you might imagine. I was deep in archives, and I was fortunate enough to take three research trips to Georgia while I wrote the book, beginning with a road trip with my father back to the family land. And some of those trips included a trip to the Georgia Historical Society, where I worked in the microfilm, and I did a week at Emory University in the archives. So a lot of time and library shelves. I’ve got two shelves worth of books that I accumulated at home, some of which are mentioned in the acknowledgments. A lot of them were novels set during that period too, or novels written that were actually during that period I should say, in Georgia and other parts of the South that really helped me adopt, I hope, a better ear for the Southern dialect and for the cultures and the moors of the time. Probably the first book that was useful to me was a book called The Tragedy of Lynching by Arthur Raper, which really shaped the book in the early stages, that I was describing where I wasn’t quite sure what the shape of the book would be. I knew that I wanted to set it in the 1930s—my dad was born in 1932—but I read that book early in the process, and it’s about six lynchings that take place in the state of Georgia in 1930. Between 1927 and 1929, there were no lynchings in the state of Georgia, and in the Georgia Historical Society archives, I found this really chilling headline in a newspaper. It was December 1929, “Lynching To Be A Lost Art,” and then January of 1930, there’s this horrific lynching in Ocilla, Georgia, which is 10 miles from where my father was born a couple years later, where a thousand people were said to come and participate in the dismembering of this young black man who was said to kill a young white woman. And so then I began to think about that year, in particular, and what kind of economic and class forces were taking place in that time that would have contributed to something so horrific, this real sort of snowball effect of hate and mob violence in that state, and so I invented a seventh incident of mob violence and just sort of inserted it in that history, and invented a county, but really took on a lot of the characteristics of those other lynchings that were real.

One thing that really struck me, is that there are obvious ways in which this is so rooted in a specific place and a specific time, but the parallels to our current reality are so uncanny. Was that something that, while you were writing, was very present for you?

Right now it seems so chillingly relevant, but when I started writing it, no. I worried that it wouldn’t be relevant enough, and, of course, I, like many white Americans, was probably living in the dark. But when I started writing this book six years ago, I wondered, “Does the world need another book about Jim Crow? We’ve clearly learned our lesson about that one.” And I thought it would be just a personal obsession of mine. So it’s been a kind of startling recognition over the course of the last few years, through the Black Lives Matter movement and then of course into the Trump era and then with the devastation of Charlottesville, just how horrifyingly present that moment still is. We’re still living in the Civil War, and I think a lot of the hurt in the book, which leads to a lot of hate, comes from that loss. And I don’t think I really understood that before I started writing the book.

The Twelve-Mile Straight is available for purchase now