Entertainment

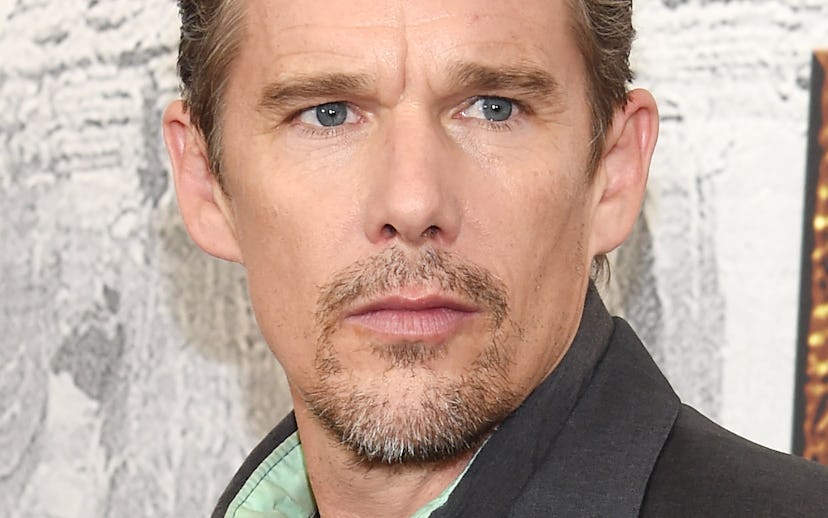

Ethan Hawke On Committing Onscreen Violence, His Daughter Becoming An Actress, And The Roles That Got Away

His new movie ‘In a Valley of Violence’ is out tomorrow

In Hollywood terms, Ethan Hawke has seen and done it all. Since his acting debut in 1985’s Explorers opposite River Phoenix, Hawke has been everything from a Gen X poster boy to an Oscar-nominated screenwriter (for co-writing Before Midnight) to an unlikely action hero in movies like Assault on Precinct 13 and Training Day, the latter of which earned him his first Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor (the second came in 2014 for Boyhood). And as his Broadway and off-Broadway resumes will tell you, Hawke takes the craft of acting very seriously. But that doesn’t mean he doesn’t like to have fun.

This Friday, audiences can watch Hawke as the archetypal lone gunslinger in the jagged Spaghetti Western, In a Valley of Violence, from director Ti West. In the low-budget film, Hawke and his canine companion Abby (in one of the best performances by a dog you’ll ever see) roll through a desolate border town on their way to Mexico, only to run up against a gang of nihilistic hooligans who commit an act of violence against him so vile that Hawke spends nearly the last half of the movie seeking his bloody revenge.

In a Valley of Violence, with its visceral death scenes and twisted sense of humor, is a very different kind of Western than September’s blockbuster The Magnificent Seven, which also starred Hawke as part of an ensemble cast that included Denzel Washington and Chris Pratt, and which, while depicting the death of what felt like hundreds of anonymous gangsters, shies away from showing the bloody consequences of real violence. We spoke to Hawke earlier this week about this distinction, why we find revenge fantasies so appealing, the roles he almost got, and what he thinks about his daughter, who currently studies acting at Juilliard, following in his footsteps.

At this point in your career, where you’ve done so many different kinds of films with so many different filmmakers, what motivates you to choose a project as opposed to when you were first starting out. Is it different?

Yeah, I mean, definitely trying to keep myself off-balance is a goal. When I was younger, that was really easy to do. Every situation was new. A lot of this movie, In a Valley of Violence, stems from conversations I had with [the producer] Jason Blum—we did Sinister and The Purge together, both of which were very successful—who was like, "I want you to do another." But I was like, "I have to be done with the scary movies for a while." And I said to him, "I don’t see why you don’t do a Spaghetti Western." The history of genre movies is such that there’s the Hollywood Western, and that’s one thing, but there’s also the low-budget Western.

And you just did the Hollywood Western with The Magnificent Seven.

But, at that time, I hadn’t. I said,"Let’s bring back the Spaghetti Western!" And apparently, Ti West had said the same thing, so Jason put the two of us together. I just kind of keep trying to put myself in different situations, to push myself, and when I was finished with it, coincidentally, Antoine Fuqua was making a Hollywood Western, and I thought, Oh, I’ll do that too.

And in that one you play more of a character role in a larger ensemble. Which do you prefer? Being a lead in a small thing like this, or being part of a bigger cast?

The thing I prefer is shaking it up. It’s fun to be the lead because it’s really challenging and everyone’s relying on you—it’s like getting to be the quarterback. But it’s really fun to play with hall-of-fame performers. You don’t mind not being the lead when you’re on a horse next to Denzel. If he wants to carry the flag, let him carry the flag. To me, getting to work with a young guy like Chris Pratt, and working with Vincent D'Onofrio and Peter Sarsgaard, there are so many great actors around on that shoot that it’s on one aspect less challenging, but it is fun to be a part of a team.

Both of these movies are very violent in their own right, but it’s a different kind of violence. In The Magnificent Seven, hundreds of people are being gunned down, but you don’t see any blood, whereas In a Valley of Violence features more visceral death scenes. Which do you see as being more violent?

Violence in movies has a moving bar, there’s no rule to it. People perceive Training Day as one of the most violent movies I’ve made, but two people get killed in Training Day, and, I don’t know, 600 get killed in Magnificent 7. But the violence is not quite realistic, it’s set in this fictitious world where violence is a metaphor, all the bad guys are dressed the same, they’re anonymous. It doesn’t mean as much as when Denzel kills Scott Glenn in Training Day. And when that cholo gang has me in the bathtub, it’s scary, it’s violent. So the rules to violence change. One of the things I like about In a Valley of Violence is you see the character is trying to heal from violence, and then get seduced into horrible violence. When I murder that guy in the bathtub, I murder him. You start wondering if your good guy is such a good guy.

When you’re committing violence onscreen, do you take satisfaction from it, or do you find it revolting?

The mystery to me about the whole profession is it’s a hard thing to talk about—your body doesn’t know it’s acting. If you spend the day crying, you feel like something horrible has happened, and it’s really hard to shake it because you’re tricking your imagination into believing this is real. When you’re doing it well, you believe it’s real. For example, if you’re doing Macbeth every night, it’s basically doing an incantation or a guided meditation about murder, and you walk yourself through it. Like, "Okay, I am going to imagine that because I want to get ahead, if I just kill this one dude I will get ahead." So I find ways to believe why I might do such a thing, and then you walk your body through the feeling of how guilty you feel after you did it. And then you start trying to lie to protect it. Shakespeare is a genius—Macbeth is brilliantly written. He really guides you through how one lie creates a murder, which creates two murders, which creates 10 murders, which creates a fascist dictator by the end. You’ve guided yourself in how to believe you did that. You’ve cried, your wife has committed suicide, you are exhausted.

What I’ve learned or what I’ve been trying to learn as I get older is that the more deeply you touch these emotions, the more free you have to be to let them go. Like a kid, you really have to play. Does [committing onscreen violence] feel good? It can. And it can feel awful. There’s no part of me that wants to play a scene where I have to slit a guy’s throat. Because if you do it right, you realize how emotionally confused a person must be to do such a thing, and you have to kind of put yourself there. It’s the same with scenes that deal with sexuality. Your body doesn’t know that chick isn’t kissing you for real. You do a love scene with Angelina Jolie, and you’re body’s like, This is great!

Most people can’t relate to the feeling of wanting to avenge the death of a loved one. So what do you think it is about revenge fantasies that appeals to audiences so much?

People like simplicity of feeling. One of the things that you hear Obama criticized for is his ability to do nuance, but we want things to be simple so bad. It’s very hard to really understand that other people have a viable point of view, and the only way to really communicate is to understand their point of view. Sometimes you just want to punch them in the face. Jack Nicholson, for his whole career, played a kind of character. He explored the same kind of man his whole career. It’s this mischievous guy who didn’t play by the rules, a guy who didn’t care about getting in trouble. And I think why we were all so drawn to that character was because we all worry about what people are going think about us. We don’t want to get in trouble. So we enjoy watching a character who doesn’t care. There’s a part of us that always wishes when a guy pisses us off we could go run and kick him in the face.

Have you ever experienced a love for an animal that your character experiences for his dog?

I have had that experience of love before. I am amazed by how much violence against animals upsets people. In Magnificent 7, if there were 200 rabid dogs coming at us and we were shooting at them, people would hate the movie. You can just kill guys, but if you’re just stepping on dogs and killing dogs, it would be hated. It’s a very complicated question, because then, how in the world do we allow slaughterhouses to exist? We are fucked up and confused creatures. My joke is every single movie I’ve ever done says, “No animals were harmed in the making of this movie.” They should say, “except every day at lunch.” Every day at lunch we killed a ton of cows and fish and chickens. We chopped their heads up mercilessly and shoved them in our mouth. We have this incredible compartmentalization, and sometimes, I think it is our incredible guilt of the way we have treated the planet that we do not want to see an animal be hurt. And in another way of saying it, we are shepherds and dogs have been our great allies throughout time. Even the biggest jerk in the country sometimes has a dog who loves him. The Ku Klux Klan leader has three Dobermans who think he is the king.

You were almost cast as Dr. Strange, and now that the film is nearing its release date, is it strange seeing posters and commercials for a film you almost starred in?

No. It might be hard if that was a part I really wanted. It’s not that I didn’t want that part or wouldn’t have enjoyed playing that part, but my goal in life is not to play Dr. Strange. If I had wanted to play R.P. McMurphy in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Matt Damon got it, I could imagine being apoplectically jealous. We’re in the age where superheroes are dominating the box office, and that was never my goal. I like comic books and I like Marvel movies, but my goal was to be a dramatic actor. So, for me, to get to be in a movie like The Magnificent Seven, a movie that plays in all the malls across America, where I get to be a dramatic actor, where I don’t have to wear a cape, I get to be a human being—that for me is very rewarding.

To answer your question, is it weird? It is weird. I don’t know what to say about it. I screen-tested for A River Runs Through It. This has been my life. For every movie you see, there’s a handful of guys who didn’t get that part. I tested for Titanic! And there are jobs you are close to, jobs you almost got, jobs that I’m so glad I didn’t get. There are jobs I auditioned for that I didn’t get that I’m grateful I didn’t get, there are jobs I turned down that I wish I didn’t, so that feeling is nothing new to me, but it is strange.

Your daughter is studying acting at Juilliard. Do you like the fact that she’s following in your footsteps?

I enjoy it because she takes it so seriously and thinks about it in such the right way. My daughter wants to be an artist, meaning I don’t think she is really coveting... some young people want to be famous. My daughter has seen firsthand some of the demons and poisons of this profession and some of the glory, and the fact that she sees it as attractive makes me happy. I keep telling her if the goal is to be 75 and teaching acting and loving it and enjoying it, then you can pursue that goal and no one can take it away from you. If your goal is to be a hotshot and have people kiss your ass, you might be miserable. No one will ever kiss your ass enough, and everyone is going to make fun of you, and that’s part of the job.