Before thinking much about the Young Adult novel, it's important to consider the state of young adults. First: What even is a young adult? When it comes to genre fiction, a young adult is an adolescent, ranging in age from eight to 16 approximately. When it comes to real life, a young adult is more often used to describe someone in their early 20s, perhaps still in college, perhaps not far out. This age differential between the young adult as a target audience and the young adult as a member of society is of particular note because of the fact that the literary descriptor "young adult" is itself a relatively recent construct; books used to be for adults or for children, and that was that. There was some overlap, to be sure, but there was no defined target audience in between the two.

All that changed in the mid-20th century as the American conception of youth transformed dramatically, revealing a whole new demographic that could be marketed to. The rise of the teenager in American popular culture can be clearly tracked in mediums like television, film, music, and, of course, literature. And while the teenage years might previously have been not much more than a time to prepare and practice for adulthood, they bore their own unique responsibilities and importance; these years were newly identified as being incredibly formative, a time of creation and even recreation.

And there is no figure who more clearly demonstrates the powers of transformation than a teenage girl. By her very nature, a teenage girl is going through radical, often painful transformations—both physical and mental. And while it is a collective process—every grown-up was at one point a teenager—each journey toward adulthood is still singular; every trauma and every triumph exists on an individual level. There is, then, no better time to seek representation outside of one's social circle, in television shows representing similar struggles, movies with recognizable character tropes, song lyrics that are identical to our most secret thoughts, and, always, in the pages of a good book.

As the notion of what it is to be a teenage girl has changed over the decades, so has the way in which she's been represented on the page. There is perhaps no better reflection of the shifts in our society's ideas of what character traits are most important in young women than by examining how they are portrayed in popular culture. Of course, there is—and always has been—plenty of room for subversion in literature; while books geared toward young adults have often been disdained for being "easy reads" and low-brow, the genre has, in fact, been a fertile ground for laying the seeds of cultural dissent. Or, at the very least, YA novels have served to help their readers question the traditional roles young women have been expected to play, and demonstrated through vibrant, intelligent characters all the ways in which young women can exist in—and even change—the world.

This is not to say that the evolution of the teenage girl in Young Adult novels has been flawless—or even close to it. It's only in recent years that there has been anything even resembling accurate representation of real diversity in these books; historically, culturally marginalized groups were left off the page much as they have been shunted to the fringes of American society. But that's started to change, and will only continue to do so as readers demand more and more to see themselves represented, their voices heard, their voices shared, and the stories of their lives told.

Here then, is a look at the evolution of the teenage girl in the Young Adult novel.

LITTLE WOMEN, Louisa May Alcott (1868-9)

While not originally released as a YA novel (this was, after all, almost a century before that designation existed), Alcott's classic book introduces four of the most familiar and long-standing teenage girl archetypes: The Good One, the Rebellious One, the Dead One, and the Young One. It's tempting (and not inaccurate) to see each of the four March sisters—Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy—as distinct characters, so separate are their personalities, so individual are their ultimate pursuits. And yet, it's also instructive to view them as part of a larger whole, and that whole being the ideal of a teenage girl in the mid-19th century.

Meg is the obedient daughter, the one who aspires to be exactly what a young woman of her station ought: kind, faithful, quietly intelligent, and with no thoughts beyond wife- and motherhood. Jo, of course, is rebellious; she's brash and demanding, exacting and proud. She's also fiercely smart and independent, driven by career ambitions and passionate causes. Beth... well, Beth dies. But did Beth ever really live? Not, like, really. Oh, she played the piano, I guess, and was a good listener. But she is nothing if not a representation of what happens when a young woman has no further life goals than niceness. Spoiler: You wither and die. And then there's Amy, who's something of a wild card. She is spoiled, yes, but also conscious of the workings of the outside world and its demands in a way that is fascinating and superiorly interesting. She doesn't just want to make a home like Meg, nor will she be content to be wild and alone, like Jo. Rather, Amy wants to be successful on the terms of the world at large and of herself.

Take all four of these young women together, and you won't find a better representation of the struggles that young women (albeit, in this case, privileged, educated young white women—a very important distinction) faced in that time period, as they tried to navigate a world that didn't much care what they did, so long as they eventually bore children. Alcott proved with this book that there was more to the interior life of a young woman than just her future family; that existed, to be sure, but so did a myriad of other hopes and dreams, all equally valid, all hopefully possible.

ANNE OF GREEN GABLES, Lucy Maud Montgomery (1908)

This beloved series was not specifically intended for young adults but has become an important touchstone in the more than a century since it was first published. Like Jo March, Anne Shirley is bright and talkative, as well as prone to getting into trouble while on the quest for adventures. But unlike Jo, Anne is an orphan. This is a common enough occurrence in YA fiction; children are often parentless or under-parented. This lack of authoritarian oversight allows the YA protagonist to find her own way through the difficulties of the world, proving her strength and resilience. Such is the case with Anne, who navigates life's troubles with a sense of purpose and determination. But also, as befits the time in which she lives, Anne puts obligations to home and family over her own immediate desires; a decision which pays off in the form of finding love and companionship, and serves as an example to young women readers of what to prioritize, and how doing so will not mean an abandonment of your values or self-worth.

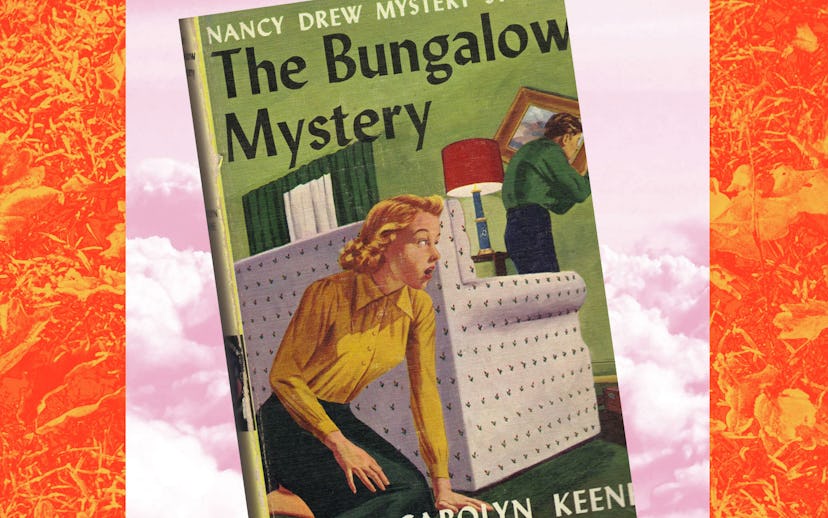

NANCY DREW MYSTERIES, Carolyn Keene (1930)

This series has been in existence for some 80-odd years, and it's easy enough to study it and draw conclusions about the evolution of the teenage girl based on how Titian-haired Nancy Drew developed. After all, Nancy has, from the beginning, been reflective of the feminine ideals of her times (so eager! so courteous!) while also rejecting them (so self-righteous! so insatiably curious!). But then, beyond those character traits and her propensity for solving mysteries, what do we really know about Nancy, other than that she has strawberry-blonde hair? Not much! But that's okay because it's sort of nice that she was allowed to be a blank slate. It means she could be anything. And so could we.

THE LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE SERIES, Laura Ingalls Wilder (1932-1943)

Not strictly fiction (though certainly employing no small amount of artistic license), the Little House books, though set in the '70s and '80s, were published in the '30s and early '40s. This is significant as they served to depict a hardscrabble existence and a perseverance in the face of odds including displacement, class struggles, and loss, which were easily recognizable for children who were growing up during the Great Depression. The Laura of Little House was a plucky survivor—something young women of future generations needed to see during their own down times.

A TREE GROWS IN BROOKLYN, Betty Smith (1943)

Francie Nolan is an unforgettable character because of how remarkably normal she was. Yes, she was bright and curious and plucky in that oh-so-familiar YA way. But also, Francie was frequently disheartened; her world was one of disillusionment, of poverty and hunger, alcoholism, and untimely deaths. Yes, she persevered, but there was nothing particularly poetic about it; or, rather, the poetry was quiet, not grandiose. The simplicity of Francie served as a fascinating counterpoint to the grandiosity of World War II-era America; Francie's strength was a testament to the backbone of our society, rather than its bells and whistles.

ALL-OF-A-KIND FAMILY, Sydney Taylor (1951)

There's no doubt that a certain kind of teenage girl predominated in Young Adult lit in its beginnings, and it can be summed up in a word: white. For all the myriad personalities and even socioeconomic types represented in books like Little Women and Anne of Green Gables, all the main characters were white, and they were also all Christian. This is why Sydney Taylor's All-of-a-Kind Family was so revolutionary; yes, Ella, Henny, Sarah, Charlotte, and Gertie were all white, but they were also Jewish in turn of the century New York City. They represented a distinctively different mode of life than did, for example, Francie Nolan in A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, and offered Jewish readers in America a glimpse at familiar traditions that they'd be hard-pressed to find elsewhere. The importance of this—particularly immediately following World War II—can not be overemphasized. This type of representation goes a long way toward cultural inclusivity and normalizing what had previously seemed like the "other."

A WRINKLE IN TIME, Madeleine L’Engle (1963)

L'Engle did something really different with this book in that she allowed women to take center stage in a story that was science-based. Sure, that might not sound so revolutionary now, but this was the early 1960s; women weren't even allowed to open checking accounts without a man's permission. What L'Engle did with Meg Murry was offer a look at a troubled, complicated, smart young woman who did everything her smart AF little brother could do, only better—even if in a totally imperfect way. This book is also loaded with tons of anti-communist propaganda, which serves as a reminder that it was written during the arms race between the U.S. and Russia, which also puts all the physics talk in perspective. We were shooting for the moon! Women too. What a time.

HARRIET THE SPY, Louise Fitzhugh (1964)

Is there any more iconoclastic young woman than Harriet the Spy? She's thoroughly unlikeable, if completely lovable; incisive and cruel at times, but never because she intends to hurt, more because she is hurt. Harriet came along at a time when young girls and women were still supposed to focus on how to make the world better (it usually involved a level of docility and compliance), and yet she was difficult and willful, made big mistakes and simply longed to be understood by anyone—even, especially, her parents, but also, of course, her friends. Harriet exemplifies the desire to make your own way through the world, and then realize you need to retrace your steps, and probably clean up some of the messes you made along the way before you can confidently go forward.

THE OUTSIDERS, S.E. Hinton (1967)

This pivotal work of YA fiction was a real departure from the books which strove to present teenagers as having a squeaky clean image. While the dominant characters in this book are male, teenage Cherry is an interesting study in a flipped-on-its-head stereotype: the good girl attracted to the bad guy who still manages to stay true to herself by not completely throwing away her future, or compromising her values. Cherry is living in between two worlds, navigating it as best she can, and there's no way that this was not incredibly, instantly identifiable for every young woman who read this book in the late '60s.

FROM THE MIXED-UP FILES OF MRS. BASIL E. FRANWEILER, E.L. Konigsberg (1967)

In some ways, this book is reflective of simpler times than the tumultuous late '60s; in others, it's a perfect reflection of its era. The fact that 12-year-old Claudia escaped a life of straight As and emptying the dishwasher in her Greenwich, Connecticut home in favor of living amid art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is evocative of the desire of so many adolescents of the time: to turn on, tune in, and drop out. Of course, Claudia and her younger brother Jamie (he provided the funds for their escapade) do wind up returning home, and the story is mostly just charming, and not particularly transgressive. But sometimes, that's all you need. And sometimes, charming and not particularly transgressive is actually all we really are.

DADDY WAS A NUMBER RUNNER, Louise Meriwether (1970)

This isn't exactly a YA book, and yet it's a perfect example of a coming-of-age book and great evidence of the abandonment of smoothly palatable stories for teenagers. Francie Coffin is a black teenager growing up in Depression-era Harlem and is a mirror version of that other famous YA Francie—Nolan of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. While both Francies lives are full of trials, it's very clear that Francie Coffin—despite being bright and having ambitions beyond the limits of her poverty-stricken neighborhood—has nowhere near the options to rise about her surrounding that Francie Nolan does. While set in the 1930s, this book is emblematic of the time of its release in that it struck a blow against the dominance of white girls in YA fiction, as well as refusing to romanticize the struggles of young black women in America.

ARE YOU THERE, GOD? IT'S ME MARGARET, Judy Blume (1970)

Judy Blume excels at revealing the interiority of a young woman's mind. Perhaps no better book portrays this better than Are You There, God? It's Me Margaret, which presents a teenage girl whose preoccupations include such incredibly important things as: will she ever get her period, will she ever get breasts, will she ever get kissed, and is religion real? The way that Margaret's questions veer between trivial and profound is reflective of the way every day feels like the most important day of her life for a teenage girl. Also, though, Blume reflects an analytically happy cultural time, one in which Alexander Portnoy had just been introduced to the world; but the fact that Margaret's thoughts and feelings were being voiced from the perspective of an adolescent girl was, in its way, far more transgressive than anything Philip Roth was up to at the time.

JULIE OF THE WOLVES, Jean Craighead George (1972)

Beyond being beautifully written, this book deals with incredibly pertinent issues surrounding the displacement and lingering trauma suffered by indigenous Americans, the importance of wildlife preservation, the difficulties of being a young woman in a patriarchal society, and marital rape. The frankness with which George writes about these sensitive topics is a testament to the relatively open times, and a desire to explore those topics which had long been hidden from our country's collective conscience. So while this book is usually shelved in the children's section (even more so than in the YA section), it's a really valuable read for teenagers of all eras, as it speaks to issues which transcend time.

ROLL OF THUNDER, HEAR MY CRY, Mildred Taylor (1976)

Much like Louise Meriwether (Daddy Was a Number Runner), Taylor set her book about racial inequality and the white American-perpetrated domestic terror campaign against black Americans during the Great Depression. This book is gentler in its approach to the traumas of systemic racism, but also makes a great impact in the way in which it makes clear that the difficulties of adolescence involved very different things depending on the color of your skin. But also, this book is an example of the way in which black teenage characters were rarely allowed to live outside traumatic roles in YA books; their representation was not anywhere near as varied as that of white girls.

THE GREAT GILLY HOPKINS, Katherine Paterson (1978)

The '70s were definitely the right time to throw away all notions of what a family is supposed to look like, and perhaps no book of the time does that better than Katherine Paterson's The Great Gilly Hopkins. Paterson is remarkably adept at dealing sensitively with difficult issues (see also: Bridge to Terabithia) and handles the topic of foster care beautifully. Gilly is an essential fictional creation for readers who are struggling with their own issues of identity, belonging, and figuring out what family really means. So, basically, Gilly is essential for all of us.

THE WESTING GAME, Ellen Raskin (1978)

Darkly hilarious and consistently clever, this mystery novel presents an unlikely heroine in Turtle, a 13-year-old who has violent (though understandably so) tendencies and an ability to piece together even the most inscrutable mysteries. More than that, though, Turtle is fascinating because a huge part of her role is to dismantle any signs of traditional, oppressive femininity, and to help free her sister from the burdens of the patriarchy's expectations. What better hero can you imagine for the late '70s teenage reader? None.

ANASTASIA KRUPNIK, Lois Lowry (1979)

What a gift to the world of YA books is Anastasia Krupnik. Like many of her readers—like many young girls—she's an incredibly astute observer, cares intensely about things like the wart on her finger, has misplaced delusions of grandeur (no, the dates do not add up; she is not the long lost murdered tsarina Anastasia of Russia) and is not the world's best poet. But what Anastasia is, makes up for all that; she is most definitely a kid without any of the responsibilities of an adult. This is significant because it symbolizes a shift away more traumatic YA narratives (oh, they're still around; this is also the year V.C. Andrews released Flowers in the Attic, but that's another story), and back to a sort of innocence not seen since Harriet the Spy. Anastasia isn't innocent exactly—she's too bright for that—but she doesn't have the weight of the world on her shoulders, just the weight of her world. This is a privilege, to be sure, but it also signifies a return to a certain kind of normal, warts and all.

ANNIE ON MY MIND, Nancy Gardner (1982)

Let's face it, lots of YA novels have teenage girls with blurred sexual identities (think: Nancy Drew's best friend George), but it wasn't until the '70s and early '80s that sexuality became more explicit in mainstream YA books. A prime example of this is Nancy Gardner's groundbreaking Nancy on My Mind, which explores the relationship between two teenage New Yorkers, whose friendship develops into something more than merely platonic. Their blossoming love is presented in a matter-of-fact way, one which is instantly relatable and a much-needed type of representation in the YA universe. Oh, and here's a cool thing: The two teen girls weren't cosmically punished for the fact that they loved each other. Like, neither died. This is actually revolutionary when it comes to how gay teens were depicted in fiction up till then. But, you know, turns out it is possible to love someone of the same gender and go on to live a full and happy life, and that's exactly what Gardner's book shows.

THE HOUSE ON MANGO STREET, Sandra Cisneros (1984)

This beautiful coming-of-age book by Sandra Cisneros has an impressionistic feel which beautifully parallels the half-formed thoughts that flood the mind of the adolescent girl. Esperanza's age is never revealed, but that's ok. It's sufficient to know that she is in the process of growing up and out of and maybe back into the tumultuous, imperfect, wonderful place she calls home. At a time when this country's president was condemning minorities who lived in poverty and when the anti-immigrant talk was heightened, the importance of a work like Cisneros' can not be overvalued. Esperanza demonstrated the absurdity of denying humanity to huge swathes of people, simply because of their socioeconomic class or their ethnic background. And Cisneros did all this with truly lyrical prose, all the better for readers.

THE BABYSITTER'S CLUB SERIES, Ann M. Martin (1986)

Hey! So, it's the '80s. Time to have a little fun, eat some candy (well, not so fast, Stacey), wear some truly inventive outfits, and make some money! If any book series is more reflective of its times than the BSC, I don't want to know about it. Ann M. Martin's super popular series about a group of teen girls who are all about working (yay, capitalism), but also about friendship (yay, a healthy amount of popularity). They love their suburban life (every venture to nearby New York City involves encountering intimidating 13-year-olds in black, off-the-shoulder cocktail dresses), and who wouldn't? Life is perfect. The club is even demographically sensitive, what with its one Asian and one black member. There's even a redhead with glasses!! Honestly, this series so perfectly distils the spirit of what being a teen girl in the '80s was supposed to be about, that I can only hope it's safely stored in a time capsule somewhere, so that someday, our alien overlords will be like, Really? This is what life was like for teenage girls? How... basic.

THE DANGEROUS ANGELS SERIES, Francesca Lia Block (1989)

So, maybe the Babysitters Club was basic, but not everything in the '80s was polo shirts and snobby country club kids. There was also Weetzie Bat. Block's Dangerous Angels series centers around the magical, mystical life and times of Weetzie in Shangri-L.A. and has been a controversial set of books ever since its debut. Why? Well, because Block had the audacity to incorporate timely topics like gay relationships (gasp), the AIDS epidemic (GASP), abortion (GASP!!), and children born out of wedlock (GASSSPPPP!!!!). But, of course, this is what makes these books so necessary. Weetzie might have lived in a slightly distorted version of the real world, but, hell, to what teenager does the real world not seem to be slightly distorted? Or even majorly so? The '80s were a messed up time, Weetzie was just living in it. So were her readers.

PARABLE OF THE SOWER, Octavia Butler (1993)

Butler's science fiction masterpiece centers around a young woman named Lauren who is a super-empath who watches as society collapses around her and everything she loves is taken from her; so she does what one does in that type of situation: she starts her own religion. But so, the early '90s were a time of societal chaos. Unemployment was at record highs, the economy was tanking, crime rates were atrocious across the country, the prisons were filling with more and more black and brown bodies. For Butler, a black writer, to create a character who was changed by everything that touched her, who was ultrasensitive as if to challenge the racist notion that black people are more impervious to pain, was a revolutionary thing. Butler's work demonstrated her own preternatural sensitivity, to her readers and to the times they lived in; times which called for a deft touch, lest everything come crumbling down.

SABRIEL, Garth Nix (1995)

Every generation needs a hero, and Sabriel is one who actually transcends history, walking her feminist fantasy path in a truly distinctive way. The plot is both simple and hard to easily sum up: Sabriel goes on a journey to find her missing father. But, of course, there's so much more: Sabriel is about learning how to live life in the way that is most true not only to who you are as a person, but according to the needs of those around you—the people you love, yes, but also, society at large. And Sabriel is feminist mostly because of how unconcerned with gender it seems to be. It doesn't matter that Sabriel is a young woman, she just is one. This is quietly revolutionary, the implicit way Nix presents this reality. And coming out, as it did, at a time of peak identity politics, it's an interesting counterpoint to the constant need some people have to define who and what they are, ad nauseum.

THE HARRY POTTER SERIES, J.K. Rowling (1997)

Ostensibly, a boy is the star of Harry Potter, but we all know that the real hero of these books is Hermione Granger. Hermione is brilliant, empathetic, doesn't put up with boys' bullshit, and is brave as hell. She combats bigotry and oppression wherever she finds it. She deals with being called shrewish and a brown-noser. She isn't perfect, nobody is, but she does everything she can in her power to be the best that she can be, and elevate those around her. And she does it all in the shadow of her flashy male friend. Hermione, then, isn't just a symbol of young women in the late '90s, she's a symbol of women—young and old—always and forever.

SPEAK, Laurie Halse Anderson (1999)

Melinda, the main character in Speak, deals with a horrific rape at the hands of a school acquaintance and the equally horrific aftermath. The reality of rape culture has been addressed more and more in recent years, though its very existence is still questioned by many. Few fictional characters demonstrate better than Melinda the way young women can be ravaged by this systemic issue, and can at turns feel forced into silence or forced to speak in a way they're not ready. For any young woman who is intimately familiar with sexual assault, Melinda serves as an important touchstone and an example of strength on a young woman's own terms. And for anyone not intimately familiar with sexual assault, Speak opens a window into a horrific part of our culture, one that demands we pay attention to it, lest it continues to fester and grown.

HUSH, Jacqueline Woodson (2002)

Woodson is a profoundly gifted writer who has a particular way with YA books; Hush is no exception. The story revolves around the uprooted lives of a family with two teen girls, caused by their police officer father's testimony against two of his fellow cops, and the abrupt relocation and disavowal of their past lives that follows. This novel deals with issues of racial injustice, displacement, loyalty, and identity, and came out at a remarkably apt time, considering this country was in a place where loyalty to some conception of the state was all but mandated, and nuanced thought and complex questions were pushed aside in favor of docility and obedience.

THE BERMUDEZ TRIANGLE, Maureen Johnson (2004)

This funny, sweet book is immensely readable and approaches the always pressing (to teenagers, but also beyond) topic of navigating group friendships in a sensitive, thoughtful way. That Johnson also delves into what happens when two members of a trio of friends develop feelings for each other—and those two friends just happen to be of the same gender—is what makes this specific book stand out. It's not for nothing that this novel came out during a time in our country when there was a huge push toward legislation banning gay marriage. Johnson's teen characters are the perfect demonstration of just how normal love is—no matter who is doing the loving.

TWILIGHT, Stephenie Meyer (2005)

How exactly is the saga of Twilight's Bella reflective of teenage girls in the mid-'00s? Well, this was the era of chastity rings and pop stars proclaiming they'd be virgins forever and George W. Bush had just been re-elected and there was a generalized massive dumbing down of culture and this, THIS, was the runaway success of the YA lit world. So, yeah. It was pretty reflective.

THE HUNGER GAMES TRILOGY, Suzanne Collins (2008-10)

What could there possibly be to learn from a book about a dystopic society in which the poorest members are literally forced to sacrifice their children in order to appease and entertain the elite? Where freedom of thought and movement is a gift only accorded to the wealthiest citizens? Where past conflicts are used as a specter and threat to keep the masses under the control of the militaristic government? Hmm. It's hard to say. What isn't so hard to say is that Katniss Everdeen, reluctant hero, became an ideal emblem for the 99 percent (these books presaged Occupy Wall Street, but there's little doubt there's an element of the prophetic in them) as she faced down the Capitol, the ultimate bad guy 1 percent.

GIRL IN TRANSLATION, Jean Kwok (2010)

The world Kwok portrays in this elegantly written book is one familiar to her; much like her main character, she grew up in a poor, immigrant family in New York City, and she too excelled academically and made her way out from the poverty she was surrounded by. But also, in Kimberly Chang, Kwok gives readers a character who beats back stereotypical portrayals of Asian-Americans, and shows the difficulties inherent to straddling two worlds, languages, and cultures, and makes clear that this is an enormous burden for children to have to shoulder, no matter how gracefully they do so.

AKATA WITCH, Nnedi Okafor (2011)

Although the representation of black children in mainstream YA fiction used to be rather rare, with some publishers even making sure covers didn't depict a book's black characters, this has changed dramatically in recent years; this gorgeous fantasy tale is a prime example. It would seem that fantasy and magical realism would be perfect genres in which to incorporate diverse characters, and yet that's rarely been the case, with many fantasy writers even reinforcing traditional stereotypes in their portrayals of dark-skinned characters (looking at you, George R.R. Martin). With Akata Witch, Nnedi Okafor claims a place in the fantasy world and introduces readers to Sunny, who was born in New York, but is growing up in Nigeria, where she and some friends band together to defeat a man who kidnaps, maims, and kills children. This is one fantasy it's easy to want to make a reality.

THE FAULT IN OUR STARS, John Green (2012)

Hmm... do you like to cry? If so, you should definitely get into John Green's books. But let's not talk about dying teenagers right now; the fascinating part of this book has little to do with that, and more to do with how accurately it takes typical teenage experiences—feeling alienated and misunderstood by your parents, falling in love, not being able to imagine your future—and gives it a unique spin, amplified in part by main character Hazel's tragic illness. But also, Green's Hazel is a beautiful example of the sort of ultra-enlightened, wildly savvy teen of today, the kind who almost knows too much for them to fully process, a character trait which can be simultaneously wonderful and terror-filled. Because, well, knowing the many beauties of life—whether that means a life-altering book or what it is to fall in love—is great and everything, unless that knowledge comes at the cost of knowing it's all going to end soon. Like, way too soon. Hazel is, in many ways, the perfect teenage girl avatar for our times, living as we do in an age where information is abundant, but it sometimes feels like we know too much.

ELEANOR AND PARK, Rainbow Rowell (2013)

Rowell so perfectly captures one school year in the life of two self- and otherwise-identified misfits who are growing up in Omaha, Nebraska, in the mid-1980s, that it's incredibly easy for readers to transport back in time and place to be there with them. Of particular note is the way in which Eleanor speaks of her love for Park; it's instantly familiar to anyone who fell in love as a teenager, i.e. all-encompassing and deeply profound: “I don't like you, Park," she said, sounding for a second like she actually meant it. "I..."—her voice nearly disappeared—"think I live for you." He closed his eyes and pressed his head back into his pillow. "I don't think I even breathe when we're not together," she whispered.

See? That's love. Teenage love anyway.

POINTE, Brandy Colbert (2014)

What many YA books tend to do with their main characters is understandable, if predictable; they honor them for their flaws, or, sometimes, their lack of flaws. In other words, most YA books tend to moralize. This happens less and less as YA gets more sophisticated (we're long past the days of Sweet Valley High, wherein a character dies of a heart attack the first time she uses cocaine), but still, the moralizing happens. All of which is to say, Brandy Colbert's Pointe is so refreshing because of the way in which it lacks the implicit condemnation or celebration that usually accompanies characters doing things like smoking pot. Pointe deals with tons of heavy issues—rape, kidnapping, eating disorders—but it does so in a very recognizable way, one in which the main character, Theo, isn't someone readers look to as a hero or a villain, but just as a person.

THE GIRLS, Emma Cline (2016)

I know, I know. You're thinking The Girls is not really a YA novel, but I'm thinking: It's sold in Urban Outfitters. Besides that, Emma Cline's debut novel is really all about the teenage girl, or, rather, a very specific type of teenage girl, white, ultra-privileged, suburban, and bored as fuck. This is a novel about teenage girls in the way that The Virgin Suicides is about teenage girls, i.e. ostensibly it is, but really it's about privilege. Which, actually, is an interesting quality to project so firmly onto the teenage girl. There is an inherent benefit to being a teenager over an adult, of course; there's fewer responsibilities, more potential for do-overs, the luxury of time to make and then correct mistakes; the ability to be beautiful and excruciatingly bored. (What I wouldn't give for the chance to be bored again. I crave it.)

Perhaps, then, it is only natural that a teenager's freedom is resented by her elders; but that resentment always seems to focus on the teen girl, never the teen boy. The desperation and introspection associated with teen girls are rarely in evidence in her male counterpart, particularly since her male counterpart is one of the many people projecting onto her already.

The teen girl in YA fiction is thus a reflection of our cultural anxieties and ecstasies. Over the years she has fluctuated in the degree to which she sought her independence from family and society; she has developed from a relatively chaste paradigm of femininity into a complex creation of her own making, with wants and needs, desires and loathings, that are singular to her, even as they fit into a broader cultural dynamic. This is why it's so easy to see ourselves in the teen girl, and why it's so important for authors to actively try and represent as many facets of our society as possible in their work. Who the teen girl is allowed to be on the page is very closely analogous to who she—who any of us—is allowed to be in reality. And why would anyone want to limit that?