Entertainment

‘Friday Black’ Brilliantly Dissects The Evils Of Racism And Capitalism In America

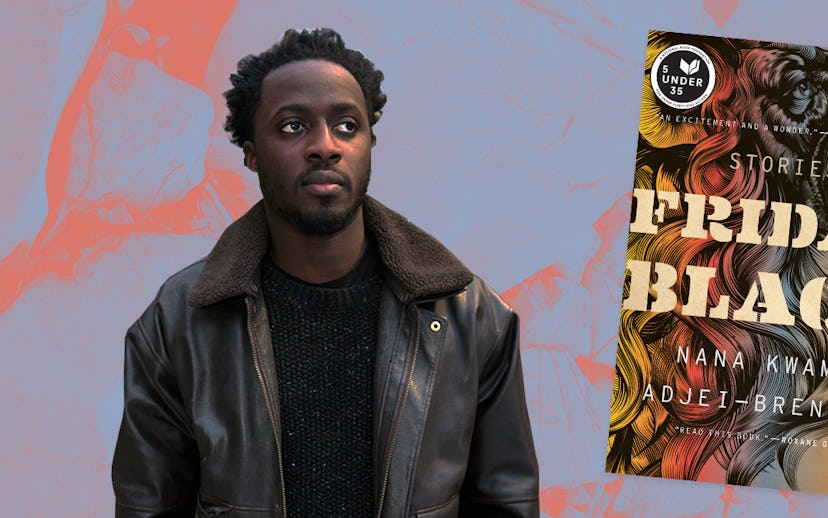

Talking with author Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

The original idea was to meet at a mall in Syracuse, New York. It's the kind of thing that sounds like it makes sense for an interview with someone whose debut book, Friday Black, has a title that references that infamous time of year for massive shopping centers (three of the book's stories are set in malls, and the titular story does, indeed, take place on Black Friday). More than that, author Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah spent a long time working in malls himself. So an interview in a food court seemed like destiny—which, coincidentally, is the name of the mall (the largest in New York state) where we'd planned on meeting.

But perhaps the mall-set chaotic cruelty that I'd just read about in Friday Black's pages had resonated with me too deeply; as I drove up to Syracuse to meet Adjei-Brenyah, I had a change of heart, and texted him, asking if he would mind if we went somewhere else, somewhere more neutral. He suggested a downtown Japanese teahouse, a quiet place where we could talk over glasses of bubble tea and matcha-infused cookies. It was the antithesis of Destiny USA—and all the better for it.

Adjei-Brenyah assured me immediately that he was glad we'd changed venues, telling me that, after his time spent working in the Palisades mall—including on Black Friday—he has no desire to hang out in another dystopian temple of capitalism. "I worked at the mall for a long time, people literally step on each other to get jeans," he said, adding, drily, "I think that's weird."

Exploring the ways in which America has normalized that specific kind of weirdness is something that Adjei-Brenyah does with an eviscerating precision in Friday Black. His stories interrogate those aspects of our culture that we have come to expect as being the price—or at least the experience—of being an American: racism, violence, rampant consumerism, white supremacy. There is an element of the surreal to the collection, evocative of the work of George Saunders, who was Adjei-Brenyah's teacher in Syracuse University's lauded MFA program. Much as Saunders does, Adjei-Brenyah tweaks reality a degree or two off its foundation in order to provide a new perspective, so that we can better see what's always been in front of us.

"I think the surrealist elements, or whatever the people want to call them, they help make the situation a bit more palatable," Adjei-Brenyah said. "Something about that displacement of reality… it allows you to get a little bit more direct, actually, toward the subject you want. That's a move that I picked up from a lot of different writers, including George."

This injection of the absurd into familiar situations also forces readers to confront the ways in which we have acclimatized ourselves to things that would once have seemed outrageous, and are now just commonplace, like stampeding over one another to get a good price on a pair of jeans, or accepting the deaths of black children as an inescapable part of life in America.

And this, maybe, is the greatest trick America, this playground for capitalism, has ever played: It's commodified and sanitized violence, because violence is good for business. As Adjei-Brenyah and I talk about his stories, and how they're bound to be framed as being "political," we keep returning again and again to the ways in which it's impossible not to be political when writing about America. He said, "I could write a story about black people in America, where I could try to totally censor it—not have any white people involved, period—it's hard for me to imagine I wouldn't be missing something. I can't write a story about America and just be like, 'Everything is great,' knowing that a lot of people are getting displaced out of their homes, you know? It's just like a huge gaping hole."

But there don't feel like there are any holes in Friday Black—or, rather, it feels like Adjei-Brenyah has stared right into the abyss of America's systemic immorality and decided to write through it, rather than around it.

When writing about the darkest of human impulses, though, things are bound to get uncomfortable; when writing about the murders of five children, as Adjei-Breyah does in "The Finkelstein Five," the visceral, disturbing, illuminating opening story of the collection, it could be tempting to sanitize the violence. Instead, Adjei-Brenyah doesn't allow readers to have distance from these deaths. This violence isn't impersonal and distant: It comes in the form of a chainsaw, it comes in the form of a boxcutter and a baseball bat.

In refusing to let anything be clean or simple, by insisting that the cost of our actions cannot be measured in terms of dollars and cents, Adjei-Brenyah confronts the ways capitalism requires that we put a price on humanity, and reveals how this has warped us as a culture.

Adjei-Brenyah said, "[We're still using] the literal economic system that allowed for literal humans to be legally bought and sold… we didn't examine the system that allowed people to be okay with that. The system that had you do that turned you into a monster. [Capitalism] forces you to think about humanity in this inhumane way. It makes you think about everything as potential: Is it going to give me money? Is it going to take [money] away?"

Reading Friday Black, it's impossible not to see how the American capitalist machine is fueled on racism, and how we're all a part of it; as Adjei-Brenyah told me, "By being born here, you are automatically implicated… These things are connected. And, more at the insidious or scary level, sometimes I like to think of racists as sort of naive, like, if only they knew better. But, no, they know better—they understand that this keeps them in power and they would rather have more power and economic viability just based on their body."

Confronting this truth head-on, this notion that most white people are perfectly comfortable perpetuating an unjust system, as long as they're still profiting from it, and doing it in a distinctively lyrical, darkly hilarious, profoundly moving way is clearly a gift of Adjei-Brenyah's. And it's one he feels lucky to be able to wield as a potential tool to dismantle an unjust system. He said, "For me, it's like, if I have a chance I'm going to say it… And it's funny because I feel for me and my friends, the last several years, every conversation leads to them being like, 'Wait, isn't capitalism evil?' And I'm like, 'Yeah. Who is benefitting from this?'… I don't know a single person who is just like, 'This is fair. This is great. This is equitable. This is sustainable.'"

There's a risk, sometimes, of looking at widespread systemic injustices and feeling overwhelmed, or full of the kind of fatalism that makes people want to retreat into the darkness, to self-care themselves into oblivion. But Friday Black isn't without hope; Adjei-Brenyah wouldn't have been able to write something so skewering if he didn't care about what he was bringing into the light. Or, as he put it to me, as we finished up our tea and ate the last of our cookies, "I don't know how you're going to achieve anything unless you really care, unless you're really invested, unless you love whatever you're talking about. Especially when it's something brutal, especially when it's something when everyone would prefer to look away."

Friday Black is available for purchase here.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.