Entertainment

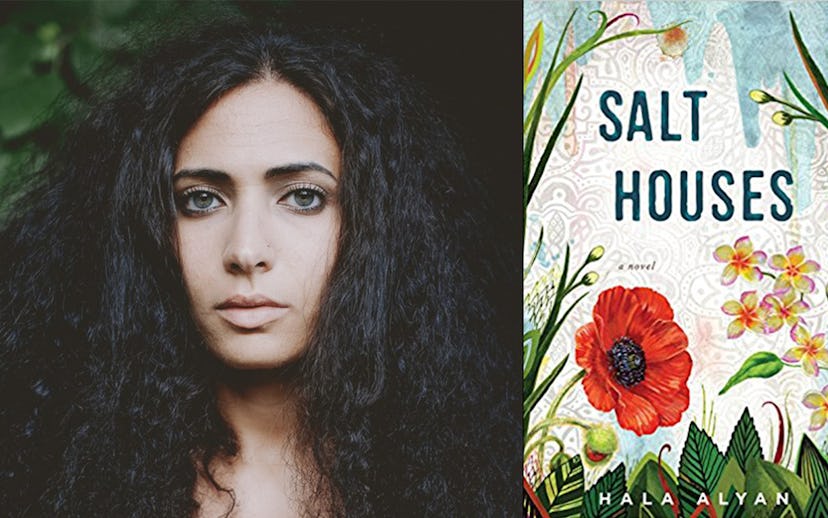

Dreams, Displacement & DNA: Talking With Hala Alyan About ‘Salt Houses’

What happens when displacement enters your DNA?

"I had a dream this morning. I’m a very active dreamer," Hala Alyan tells me, leaning in a little bit closer over the cup of herbal tea she's ordered at the Midtown Manhattan coffee shop in which we've met to discuss her gorgeous debut novel, Salt Houses. "I had a very unsettling dream this morning. I was going into my grandmother’s apartment and walking through the rooms and the doors, and I went out onto the balcony, where we spent so much time, and it was just completely... empty."

It doesn't take a psychologist (which, besides being an extraordinarily gifted novelist, Alyan is) to interpret a dream like that; after a long battle with dementia, Alyan's grandmother had just died, only a few weeks before Salt Houses was published, a book which has no shortage of powerful matriarchal figures and in which the meaning of home is explored in multiple manifestations.

Salt Houses, as I recently wrote, spans over 50 years and several generations in the life of the Yacoubs, a Palestinian family, who have relocated their homes—sometimes by choice, sometimes decidedly not—multiple times and in multiple locations across the world. An epic in every sense of the word, due in no small part to its geography (the novel is set in locations as far-flung as Kuwait, Paris, Boston, Beirut, and Jaffa), its incorporation of world-changing events (the Six Day War, Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait, the 2006 bombing of Lebanon), and the fact that the narrator changes chapter by chapter (ranging from a man in his 70s to an adolescent girl), Salt Houses also shines in its intimate details; notably, in the ways in which no character is allowed to be a stereotype, and in the way it grapples with those all too human-scaled experiences of alienation and belonging, displacement and rebuilding. Alyan might be grappling with universal problems like war and brutality, but since she renders them through the perspective of one family, through their personal triumphs and struggles, she keeps these issues on a recognizable scale.

Throughout the book, one theme resonates with extreme clarity: When you don't have an actual home, no country to call your own, no neighborhood to return to where everybody knows your name, your family becomes your home, your legacy becomes its stories. And so when Alyan spoke to me of her grandmother dying, and her disturbing dream of running through her grandmother's apartment and finding nothing, the despair which such a dream must have manifested became palpable.

Alyan continued, "And there was something about being in that space, and that space being stripped down, and my dream-self had this really intense realization of, 'Oh, she took it with her.' It’s not just that she died, but she was the matriarch of the family, and that history was lost.”

The history of a family and, by extension, of a specific culture is a funny thing. It feels at once completely stable—after all, this is history; these are things that really happened—and then also essentially ephemeral, since the type of records upon which history is dependent can vanish in the blink of an eye thanks to things like death or sudden displacement.

Like Salt Houses' Yacoub family, Alyan's family is also Palestinian and has also dealt with generations of displacement. She tells me that this is the main similarity between her family's life and that of the Yacoub's, and also explains why she couldn't draw too closely from personal experience: "I have a family that would murder me if I drew too much from them, but I took quirks. I borrowed the most from just the structural displacement. I’m very fascinated by the idea of being displaced several times over, the intergenerational trauma and movement and restlessness. I know, intimately, what it’s like to be displaced several times over, I was in Kuwait when Saddam invaded. I was four, but my earliest memories are from that time period."

This idea that displacement enters into your DNA and becomes a part of your personal and shared experience is a compelling one, and it has borne out in many studies of diasporic communities around the world. There is a pervasive sense of alienation, of not having a real home in the world. Alyan tells me, when recounting a trip that she took to Palestine not long ago, one that is mirrored in the book by one of the younger generation of the Yacoub family's own trip to her ancestral land:

Going to Palestine was a really disorienting and kind of unsettling experience in that I kind of just kept waiting for an epiphany and it didn’t come. The entire time I felt weightless and like I could float away at any moment. It was a very strange; I felt so ungrounded the whole time. I just wandered around in the heat. There was a lot of me being like, Am I intruding? Is this my space? Am I allowed to be here? Palestine becomes this thing you grow up with, and you hear about it, and your understanding of Palestine is a memory of a memory of a memory. It’s so filtered down.

But while Alyan's personal experience of visiting Palestine came, of course, with internal conflict, what she's given the reader—particularly the American reader—with Salt Houses is a chance to see a different perspective of a community that has long been dismissed and marginalized in everything from popular culture to history books. There are, in fact, few better examples of history being written by the victors than the erasure of the Palestinian people over the last 70 years; Alyan's novel goes a long way toward giving readers a glimpse into the lives of Palestinian people, not Palestinian stereotypes. Alyan says, "It’s unfortunate to have to use verbs like humanizing, but that is part of the process... [making] them think of the people as people. I do wonder if the most effective way is the simplest way. Like, I’m going to tell a story of the family, and that’s it. There is something to be said about telling the story of one person or one family, and hoping it can do something for the larger community."

This isn't to say that the Yacoub family is a stand-in for every Palestinian family or every refugee family; there is no doubt that the Yacoubs enjoy real levels of privilege, including economic and educational, that not everyone of their cultural background (or any cultural background) shares. But that is okay; in Alyan's hands, this family's pain and joys, which are intensely personal to them, speak to more universal feelings and ideas. Alyan traces a family's history and shows how a family becomes its own home, how maintaining ties like this can make you feel that rather than nowhere in the world being your home, anywhere in the world is your home—as long as you have people you love. Or, as Alyan says to me, "Your history is with other people. What you share isn’t in your neighborhood. Memory is this place that you occupy, and maybe that person lives several thousand miles away, but they share your history, and that history is your home."

Which is why, after Alyan had that disorienting dream about her grandmother's empty apartment and woke up feeling devastated, the first thing she did was call her brother on the phone, to speak to him about the loss she felt, to despair about their newly missing history. But her brother had some words of wisdom for her, ones that echo the themes in the novel Alyan had just written. He simply said to her, "Well, that’s where we come in."

Salt Houses is available for purchase now