Entertainment

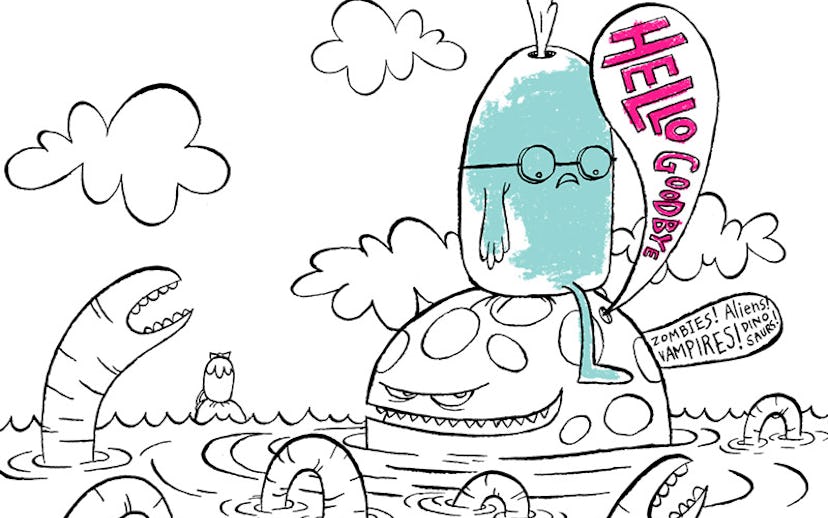

Hellogoodbye’s Forrest Kline On The Impact Of ‘Zombies! Aliens! Vampires! Dinosaurs!’

One decade in, and it’s still a brilliant album

Every generation has its go-to poppy love song. For those who started feeling real feelings during the heyday of MySpace, that song was Hellogoodbye's "Here (In Your Arms)." The bubbling electro-pop chorus touts the ever-rebloggable lyric, "Hello, I've missed you quite terribly." It remains one of the mainstay tracks on those "Hey, I really like you so here's a mix CD" mix CDs, alongside Hellogoodbye's other song "Dear Jamie... Sincerely Me." It launched Hellogoodbye out of the in-the-know corners of MySpace and into the mainstream, with appearances on MTV and Billboard charts soon after. And their album Zombies! Aliens! Vampires! Dinosaurs! has a pretty significant anniversary this week.

Indeed, Hellogoodbye's debut album turns the mighty 1-0 this week. And in that decade we've seen Facebook trump all, Limewire-like sites disappear, streaming sites manifest, EDM fist-pump its way to the top of the charts, and technicolored scenesters trade ironic Day-Glo tees for dainty stacks of rings and expensive neutrals. All the while, Hellogoodbye has been releasing outstanding music. Their sound may have veered away from the electronics, but their tongue-in-cheek lyrics and universal sentimentality remain the same. To honor the anniversary, we caught up with Hellogoodbye's frontman and creator, Forrest Kline, and chatted about everything from the impact of "Here (In Your Arms)" to imposter syndrome and MySpace being the death of the scene.

How would you describe Zombies! Aliens! Vampires! Dinosaurs! to an audience unfamiliar with the 2006 MySpace music scene?

It wasn’t a scene, it was the death of scenes. It was the internet, a sprawling free-for-all of every kind of music and ce-web-rities. MySpace exploded at the same time as consumer-level recording equipment. Musically, that's the factor that relates to the record in my mind: I suddenly had a multitrack studio and distribution model in my bedroom. And that lent itself to how the music came out; I could program full ensembles of drum machines and synthesizers and big orchestra arrangements and easily record one track of guitar direct and whispery vocals while my parents slept upstairs. I was big into the purest of the pop: The Vengaboys and Enrique Iglesias; Britney [Spears’] “Toxic” melted my mind, but I came into my love of music with bands like blink-182 and Jimmy Eat World. I had this juxtaposition in my mind of pop-you-produce and music-you-play. That was what enamored me at first, the idea that I had a similar toolset as the Swedish producers who created t.A.T.u., but that I was a kid in his bedroom. So I wanted to make some sort of hybrid, which always came out, happily, as sort of “cute.” More sugary than [Jimmy Eat World’s] Bleed American but more heartfelt than [The Vengaboys’] “We Like To Party.”

Do you look back at that time with the same nostalgia many of the listeners, myself included, do today?

In the sense that I have so many beautiful, silly, free, confusing memories from those years, yes, absolutely. I was wide-eyed 100 percent of the time, just playing with the world to see how it would react, and I made a lot of great friends then. But musically, no, not really. I’m into wildly different stuff than I was into then, and listening back to what I previously binged on usually falls into one of three categories: still objectively good and beautiful (Azure Ray’s “Sleep” or Jimmy Eat World’s “Clarity”), not something I would fall in love with today but still meaningful and cool (blink-182’s Dude Ranch or Ozma’s Rock And Roll Part Three), and the cringe category (Skankin’ Pickles “You Shouldn't Judge a Man by the Hair on His Butt!”)—nostalgia rarely plays a part. In terms of the scene, I never felt as if I belonged in any scene. That might be a bit of iconoclasm or Groucho Marxism (“I wouldn't want to belong to any club that would have me as a member ”), but I could never align myself completely with any of the scenes or sub-scenes of the time.

Were there any other songs, besides "Here (In Your Arms)," in the running to be the lead single?

The label, Drive-Thru records, wanted “Touchdown Turnaround” first. That song is emblematic of my concept of hybridizing studio-pop and bedroom-quaintism—except that the song included little of my own feelings. It was more or less an exercise in wordplay and high school wittiness. I was a shade embarrassed by it even at the time. If I can qualify that embarrassment by saying that was one of the first songs I put together when I bought a multitrack recording program. It was such a no thought, half joke, that while I respected its quirk and lack of self-consciousness, I didn’t feel represented by it. “Here (In Your Arms)” was something I could wear on my sleeve proudly. And at first, Drive-Thru didn’t get it. They didn’t see it as a single. Happily, they were always pretty open to letting me control the direction.

Was the spotlight "Here (In Your Arms)" gave the band always the goal? How did you react to that?

Oh god, no. Like I said, I often felt like a fish out of water. I came into it with this “fake” pop concept, and when it was accepted as “real” pop, I was confused. I always felt like an imposter at some MTV Spring Break concert or playing a Coca-Cola fest with LL Cool J. It never made any sense, like, “You guys know I made this in my bedroom for, like, $100, right?” I wasn’t cool in the traditional sense, or attractive in the traditional sense, or charming in the traditional sense. I think my mindset was half “I don’t belong here, and I don’t deserve to be” and half “I don’t belong here and wouldn’t want to be anyways.” That’s not to say I wasn’t grateful for any opportunity and some of the more surreal moments that came around, I always wanted to make music and travel, and I was! It was beautiful and bizarre at the same time. To make music was ALWAYS the goal, and I’m not sure I’d still be here doing it if not for most of that, so I’m immensely grateful. But it really felt like being inducted into a bachelorette party the whole time, like, “You guys sure you wanna party with me? I’m a boy… really? The sash and the crown and everything?”

What did making Zombies! teach you and how did it influence your future projects?

The first day we were supposed to begin tracking, I met with Matt Mahaffey—my absolute hero at the time who produced the record—and he said, “We’re going to a party.” I was so confused, I was stressed, we had a timeframe to finish and day one he was like “Nahhh.” But it broke my nerves and made me relax. The next day was more comfortable than it would have been. The process also taught me to abhor about what I initially loved about recording: programming and samples. I realized how much more fun and musical it was when we were in the studio playing something as opposed to scrolling through samples. Flipping through kick drum samples became my least favorite thing on the planet. "How about this one? This one? This one? This one? Or this one? This one's weird… Do you like it? What about this? How about we kill ourselves and never listen to music again?" So the next record was Would It Kill You?—which was mostly all live. After Z! A! V! D!, I threw out everything I knew about making music and started fresh with more microphones. That was a knee jerk reaction, and I find myself embracing programming, sequencing, and electronics again in more broad-view ways now, hopefully evening out my yin and yang.

As a band, what sort of pivots did you make when MySpace moved away from being MySpace?

We got a Facebook, just like any sane person.

Considering you were 22 when the album came out, what are some of the most memorable lessons to come out of your twenties?

I think the biggest, broadest paradigm shift was a sense of learning to let go, which maybe I was more acutely aware of one record later. I always saw myself as a bit uptight, I didn’t drink or do any drugs at that time because I had this idea that I wanted to be as sharp and conscious for every living moment, and to soften or alter my perception, even for an evening, was essentially diminishing my potential for life experience and knowledge. Travel was hard, being out of control of my day, my food, my location was hard. But the prolonged exposure therapy to travel, inconvenience, drugs, and alcohol eventually eased the tension in my shoulders, taught me acceptance, taught me to be comfortable with much or little. I’ll try to speak responsibly, but I would now endorse the use of alcohol and drugs later in life if you feel you can handle it. It gave me a freedom of mind, showed that my brain could run at different speeds and modes, which I find useful, influenced or not.

Finally, what has Hellogoodbye been up to of late? Can we expect a new album? And if so, what's its vibe?

I built myself a new studio which I run out of Long Beach [, California]. So far each record has been made in a new home studio built from the ground up. Apparently, they are one-time-use things. And each time, I assemble everything a bit different. I’ve come to see songs in large part as encapsulations of a particular feeling, and I’ve been feeling quite serene and a shade sexual. So it's a bit smooth.