Entertainment

A Beautiful New Memoir Explores The Complications Of Knowing How You Might Die

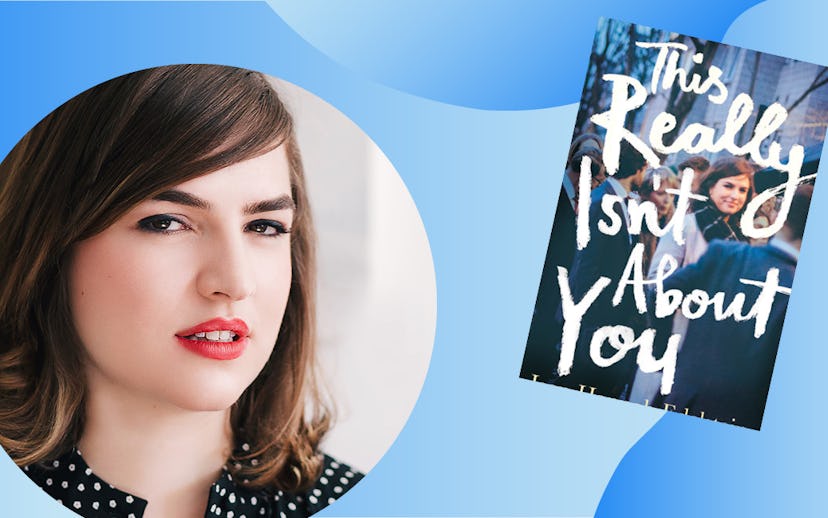

Talking with Jean Hannah Edelstein about ‘This Really Isn’t About You’

"There's no consideration of the implications," Jean Hannah Edelstein told me recently, as we chatted about the popularity of 23 and Me and other online genetics tests. "Not to be harsh," she said, "people do [the tests], but I believe it doesn't really give your comprehensive health information, because they don't actually want to break it to you that you have Lynch syndrome or you have the BRCA gene or something like that, and so it just scratches the surface... This is what I really got into in the book: When you have this information, what do you do with it?"

For Edelstein, a writer who found out in her early 30s that she had Lynch syndrome, a genetic disease that makes it 80 percent more likely its bearers will have cancer, one of the things she did with this information was write about it, and the resulting memoir, This Really Isn't About You, is a compelling, unsentimental examination of family, mortality, responsibility, identity, and love—all to say, of life itself, in all its painful, complicated beauty.

Edelstein tested positive for Lynch syndrome after her father died of cancer; he had been diagnosed with Lynch after, at a relatively young age and as a non-smoker, he developed lung cancer. (When talking with Edelstein I mention how my own father died at a relatively young age from lung cancer, and we agree that we both always feel guilty when we mention that our fathers weren't smokers, because, of course, it doesn't make them less deserving of cancer—nobody deserves cancer. But it's still something we tend to find ourselves saying, one of those many footnotes that people who talk about cancer often attach to these narratives, and a reason Edelstein said to me: "The way that we talk about cancer culturally, I think, is a huge mess.")

One of three siblings, Edelstein is the only one who has Lynch syndrome. She is the only one whose perception of herself and her future became drastically altered in a way both life-upending and anticlimactic all at once. Lynch syndrome, as Edelstein makes clear, is a peculiar diagnosis; unlike finding out, say, that you have cancer, you are only finding out the possibility that you will one day, almost definitely, get cancer. There's a finality that comes with getting the diagnosis, but there's also something open-ended‚ the knowledge that this is only a prologue, of sorts, that it only begins to tell the story of the rest of your life.

"It does change your perception of who you are," Edelstein explained. "I think at the same time, what I tried to convey in the book, is that there was this hinge of finding out something about myself that hadn't changed. It was not the same as getting a diagnosis of an illness, because I'm not ill, but rather just learning, like, okay, this is a thing I've been carrying all this time. I've been oblivious to it; I've been very relaxed, you know, about life, in a way that I can't be quite so relaxed anymore."

It is at once simple and impossible to succinctly describe Edelstein's memoir. On the one hand, it's a story about loss: the loss of her father, the loss of her carefree attitude toward her own future—one that had been utterly typical for so many 20-somethings. And yet, This Really Isn't About You is also not solely about Edelstein's discovery that she has Lynch syndrome; it is also a bracingly funny and honest depiction of being a professionally and romantically frustrated young woman, a wholly relatable narrative about figuring out who you are and who you want to be in a world that doesn't have any answers for you. This isn't to say that this memoir has disparate narratives, rather that its cohesion is evocative of the way that all our lives are made up of puzzle pieces that don't ever seem to fit as seamlessly as we'd want them to. There is chaos and confusion, bad bosses and shitty boyfriends, a crummy flat in London and an enviously large apartment in Berlin, and an adorable dog. There are all of the things that can happen in your life (not all at the same time!), with the only common through-line being you. And then when you find out something that changes who you think "you" are, as Edelstein did with her diagnosis, then everything gets even more confused. And Edelstein handled that confusion by writing about it.

"I've mostly written memoir type things," she said to me. "I'm always writing from the first person, and I think when this happened to me, I had to tell people about it. That's my way of dealing with things, I suppose, is turning them into narratives."

This isn't uncommon, of course. There are many grief-driven memoirs, and Edelstein's story is in part that. She writes beautifully of her relationship with her father, and what it means to lose a beloved parent when you are only just beginning to understand what it means to be an adult yourself. She told me, "It's like being a part of this club where you immediately identify the other members, but no one wants to be there. That was something I also wanted to dig into, how grief lingers and how you process it when you're an adult, because you think, Well, I'm a grown-up so I should be fine without my parents. But actually, if you love your parents, there's never a time when it's okay."

For Edelstein, the grief of losing her father was compounded by the fact that she would retain a connection to him that was singular among the rest of her family—she would be the only one who knew what it felt like to have Lynch syndrome. And the diagnosis meant more than just the fact that she would have to deal with Lynch's implications to her personal health, she would also have to think about how it would affect the health of any children she might want to have, and even how she would choose to have those children. As Edelstein makes clear in the memoir, women diagnosed with Lynch syndrome are advised to get hysterectomies as early as possible because of attendant cancer risks; if they want to have biological children, they are told to try and do that at a very young age, and if they want to avoid passing Lynch syndrome on to their future children, they will need to do IVF.

When Edelstein was diagnosed—and, at the close of the memoir—she was not in a relationship and was not at a point in her life when she was seriously considering when or even if she would start a family. Having to address these questions was one of the things Lynch changed for her. She said, "Obviously my 20s were like many peoples'—fairly chaotic. I never really had a very clear plan, but I feel like if I had had the diagnosis that would not have been the case. Like, I wouldn't have felt the freedom, both from the perspective of knowing that I always have to be in the position to have good health insurance or good access to health care, and also feeling like the clock is ticking towards the [hysterectomy]. If I had felt that from the age of 10, then I think that would've really influenced a lot of my decisions."

It's an interesting, if futile, thought experiment: Would you rather know that you have a genetic problem like Lynch your whole life? Or would you rather find out about it after you've lived for awhile? There's no way to go back in time, obviously, and Edelstein told me that she is sure she might have, if diagnosed as a teen, gotten married at a very young age, so that she could have children and then have a hysterectomy much sooner. But then she wouldn't have had the life she did have, one that took her out of the United States, and allowed her to live a peripatetic, exciting existence in her 20s, one that took her to where she is today: married and pregnant with a child she knows is Lynch-free, thanks to genetic screenings ("I didn't want to do IVF, but my ethical position with this information was that I had to do it").

Edelstein said to me, "I met my husband about six months after the book ends and then we got married a year later, and I think there are a few reasons for that. One was definitely because of my diagnosis. We met and fell in love immediately, but then, perhaps, if we had been 30 or I hadn't had the diagnosis, we might've just kind of been together for a while before making decisions like that."

But just because Lynch has resolutely impacted her life, it doesn't mean that it controls it. Edelstein explained, "I think this diagnosis has forced me to reckon with [the idea that any one thing controls life] more than most, in terms of [thinking], I could let this ruin my life. It really did throw me and ruined my life for a little while, but in the end, I was fortunate enough to be able to kind of just make it another part of my life."

This idea feels quietly revelatory, the notion that traumatic things can happen, and that they can be processed and absorbed; they don't go away, but they become a fact of life that we refuse to let devastate us, and instead just understand as being part of us. It's a reminder that, so often, the bad things that happen to us in life aren't about us—to echo Edelstein's memoir's title, they really aren't about us, even if they are in us. This is, I think, a helpful way of moving forward in the face of so much that feels so pointed and immediate; it's a reminder that our experiences matter, but that they are made up of so many factors over which we have no control, so whatever way we choose to navigate them is inherently the best way; we are doing the best we can, because we are doing our best.

Edelstein said she learned from her diagnosis that "having a disease or a gene is so personal, but you have no control over it, it has nothing to do with you." This idea is frightening because we want there to be a purpose in our suffering, or potential suffering; we want things to feel fated and determined based on some code that is possible to follow. But it isn't like that, our fate is not written out for us, not in the stars and not even merely in our genes. As Edelstein explained to me, though her grandmother died young, in her early 40s, her father lived to be in his 60s, and a paternal great-aunt, who also probably had Lynch syndrome and dealt with cancer, lived into her 80s. There are no certain futures, a lesson Edelstein learned and gets reminded of all the time. There is only what is happening now, and the ways you can prepare for what is likely, though not definitely, to come. And though that's frightening, it's also liberating. It has nothing to do with you, but it is still your life, so why not live it.

This Isn't Really About You is available for purchase here.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.