Entertainment

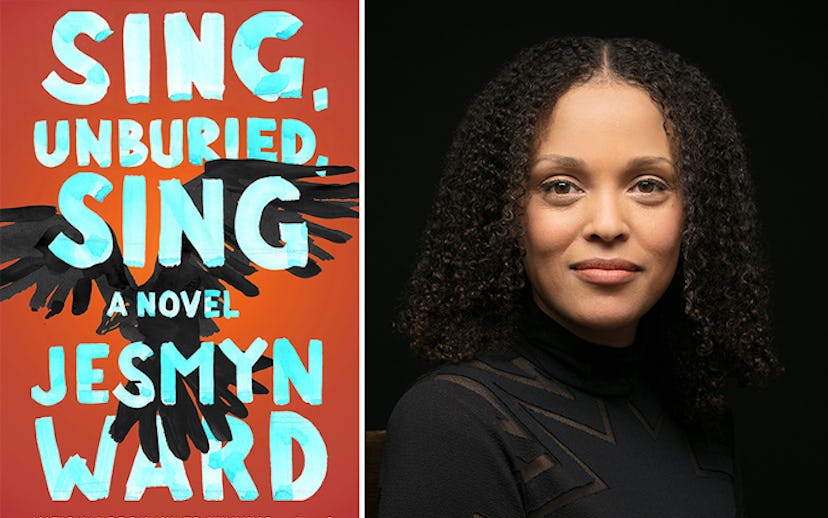

Jesmyn Ward On Her New Novel And How The South Really Won The Civil War

‘Sing, Unburied, Sing’ is out today

When I speak with Jesmyn Ward on the phone from her home in Mississippi, she’s just put her son down for a nap and is in the middle of writing a profile on Ava DuVernay. She has writer's block. “I don’t know how you do it,” she says to me, “it” meaning write for a publication. “I feel like I’m just saying the same things over and over again.” It’s funny, I tell her, because I feel similarly confused about writing fiction. I take immense pleasure in reading it, but become paralyzed at the idea of creating an entire world of my own. Especially one as layered and vivid as Ward's latest, Sing, Unburied, Sing.

Ward has taken on the responsibility of writing about the South and the people that live there. She’s been doing so for almost a decade now; she put out her first novel Where the Line Bleeds in 2008, won the National Book Award for her second Salvage The Bones in 2011, and wrote her memoir Men We Reaped in 2013, all touching on the region and its harrowing past. Though, as recent events have shown, the past never truly goes away, it just gets better at disguising itself. When I ask Ward if writing about the South ever gets to be too much, she laughs, “Oh yes, all the time. It makes me think, often, about leaving, just because it's difficult to live in a place where your humanity has been devalued for 400 years.”

But still she stays and she writes; and she does it eloquently through poetic prose, magical realism, and, in Sing’s case, through the story of a 13-year-old boy and his family as they struggle to overcome drug addiction, racism, incarceration, and personal failings. It’s a dynamic book that deserves all of the love and praise it’s inevitably going to receive.

Ahead, we chat with Ward about the loveable nature of her characters, what constitutes home, and how the devastation of Hurricane Harvey has rendered her speechless.

You've bounced from fiction to fiction to nonfiction, and now you're back to fiction. How do you approach writing one versus the other?

My process for writing a novel is completely different from writing memoir. Normally, when I work on a longer, creative nonfiction piece, I have to plot it out. I work from a pretty developed outline. I know where I'm going every step of the way. And with fiction, I don't work like that at all. It's almost the exact opposite. When I work on novels, I begin at the beginning, I begin at the first chapter. And, when I begin, I usually have a semi-solid understanding of who my main characters are and what is motivating them and what's driving them. And then I have a vague idea of where they are going as far as what will happen to them plot-wise, but I don't know much beyond that. I have some understanding of who they are and what's motivating them, but they always surprise me and I learn more about them as I write. I understand more about what is driving them, or the grief that they carry around, or the loss that they feel, or the psychic scars that they struggle with.

Whereas, when I'm writing creative nonfiction, because I have a whole world of subjects or material to work with, it's necessary that I focus from the very beginning and pick what I would use to inform the story.

Do you think you're more at ease writing fiction?

Fiction is definitely easier for me because I think that I enjoy having the freedom to create a world and to create characters. And then, once I work my way through a rough first draft, I actually enjoy revisions. Like, I enjoy the fact that I can then go in and develop it and expand it and contract in other places and really focus it so that it can become a powerful experience for a reader.

Creative nonfiction is much harder for me because it's true, and because I write about a lot of very personal things. I write about my life, my family members' lives, people in my community, and sometimes I just write about people like us. There's this saying that I've encountered in workshops: "The best work comes when you write toward what hurts you; when you write toward what is painful." And, if you do that, usually your work can be really powerful and true. But writing toward what is painful is very, very hard for me. And I find that, when I'm writing creative nonfiction, that often my rough first drafts are horrible because it's like I circle the subject and I write around what is horrible [laughs]. I don't completely leave it behind, I just circle it instead of moving toward it. And my rough drafts reflect that because they always need focus because I think, as a writer, I'm avoiding what hurts.

The characters in Sing are all extremely complex. You've said before that one of the ways your first novel failed was you were too in love with your characters. But, I have to say, outside of Leonie, the characters are all pretty lovable.

I think the lesson I had to learn is that it's okay to love them and it's natural for me to love them, but I couldn't spare them. I couldn't try to mitigate the things that happened to them in the story and in the fictional world. I feel like when you try to protect your characters like that, then you sort of strangle the story, and it's not able to come alive and take on a life of its own because you're so busy protecting your characters from what can happen to them.

After I wrote my first novel, I saw, again and again, how brutal and how painful real life can be, and I just felt like I was doing a disservice to the people I was writing about, and doing a disservice to the characters, because I wasn't being honest about the realities of life that they faced. So, I realized that I could love them, but I had to stop protecting them, and I had to be truer to the reality that a lot of my characters live in.

Is there a character in Sing that your love burns the strongest for?

I love Jojo, that's the first character that popped into my head. But, I'm about to go on book tour, and some of the places that I go, they might ask me to read a little bit, so I've been thinking about which chapters I can read and what sections I can read from. And so I've been reading from Richie's here and there, and he breaks my heart every time. I think it's surprising to me how he affects me whenever I read his chapters. I hurt for him and what he has lived through and then lived through after death, it's heartbreaking. So, right now, he's the character that most tugs at my heartstrings.

I know that Richie was based off a real boy who was in Parchman penitentiary. Did you feel extra weight writing about him and immortalizing this boy in this way?

Well, it wasn't just one boy. From what I read, there were multiple children, who were 12 and 13 years old, who were sent to Parchman prison back in the '40s. So, yes, I did feel added weight and extra responsibility because one of the reasons why I wanted to write about him and a character like him, is because he'd basically been erased from history. I had no idea children that young were sent to toil and possibly die in Parchman prison, and so I felt that writing his character was an act of unearthing. I'm bringing him back to life and writing him back into history so that others would understand that children like him existed and this is how they lived and died.

I think it scared me in the beginning because, in the first couple of drafts of my work, there were no chapters from Richie's perspective. When I discovered his character I thought, Well, maybe I can write a couple of chapters from his perspective. But I just didn't do it in the first 12, 13 drafts. My editor, once she read the manuscript, she asked me, "Well, what do you think about writing some chapters from Richie's perspective?" And, my editor's really smart, and she's my best reader, and so I thought, Okay, I'll try. The chapters there now, that's what I was able to produce because I heard him. Once I was given permission to hear his voice, I did. I heard him. And I hope he does break readers' hearts, because kids like him really existed, and because I think that his voice deserves to be amplified and he deserves to speak.

When Richie is first introduced, he's hung up on his need to get home. And, as he explains to Jojo, home isn't always a place, it can be a feeling, it can be a state of mind. What constitutes home for you?

This is going to sound saccharine probably, but I think, for me, that home is other people. I think that home is my family and my kids and my mom and my sisters and my brother and my large extended family. It's all of those people that I love who make me feel safe and who help me to understand where I come from and who I come from. For me, that's home, and those people just happen to be here, in Mississippi, my hometown, where I'm from.

Sing was your first foray into magical realism, how did you go about approaching that world? Was it intimidating?

It was definitely intimidating. I did a lot of reading about voodoo and hoodoo, and I did a lot of reading about that spiritual tradition because that's what Mam practices. And some of that is informing Richie's experience of the afterlife. But it was also daunting because how Richie perceives the land across the water, how he perceives this home that he's seeking, this place where everyone is singing, the fact that he has to journey across water to get there, and that he has to fly—all of that came out of my imagination. I had to make all of that up. I hadn't had to do that before in my fiction. I've never been responsible for building a world and populating that world and rendering that world vivid and real, and so real that the reader has immersed themselves into that world. I was nervous about that, and it definitely made me exercise some writerly muscles that I'd never exercised before, and I think it made me grow as a writer.

Did you grow up around voodoo or hoodoo at all?

My grandmother didn't practice these things, but there are stories that I heard from my grandmother and mom about people in my great-grandparents' generation who lived here who did practice some voodoo, some folk magic traditions. Especially in those generations, because they didn't have access to doctors, they used different herbs, different plants that are local to the area, in order to promote healing from things like the common cold or viruses or childbirth.

Your book, Salvage the Bones, was brought up on Twitter the other day as a necessary read in the wake of Hurricane Harvey. The events in Texas are devastating on their own, but it's compounded when you realize a lot of people from New Orleans moved to Houston after Hurricane Katrina. How have you been processing what's happening?

I've been following along on Twitter and thinking and looking at the devastation that the storm was creating in Houston, and retweeting tweets that people were posting where they were asking for help, where they're saying, "My phone is at 9 percent battery, and I'm eight months pregnant, and there's flood water in the house, and we don't know what to do, and please send help." They're posting their addresses, and I realized that it rendered me a bit speechless. I kept retweeting different people in an effort to help, and then I thought, It would be useful to probably say something right now. But I couldn't say anything. I didn't write anything new until about two years after Hurricane Katrina, and so I realized that that kind of devastation and that kind of misery, it renders me mute. It's very hard for me to talk about it and it's very hard for me to write about it. And I think because natural disasters like that are so horrific that it's very hard to process.

Do you listen to anything when you write?

I can't listen to music when I'm writing because I have to be able to hear the rhythm of the line, the rhythm of my sentences, the rhythm of different phrases of different paragraphs when I'm writing. And I have the kind of brain that doesn't work well with noise. That's why I have to write at my house or a quiet room. I can't go out and work at a cafe or something like that. I'd like to be that kind of writer, but it doesn't work for me. I hear noise… it doesn't turn into white noise for me.

Music is really important to me though. I feel like music definitely informs my writing and, for example, I wasn't able to secure the rights for it, but in the advance copies of Sing, you'll see that I have a quote from Big K.R.I.T. there, because I always have Southern hip-hop on the brain and the lyricism of those rappers, I'm always sort of thinking about it.

My editor actually gave me a package that contained a book and several field recordings from Parchman prison, I think from the 1940s through the 1950s, and so I listened to that. I didn't listen to that when I was writing, but when I was working on the revision, I'd take breaks and I'd listen to the singing and the recordings of the men who were working in the field and were singing as they worked. I think that those recordings informed my ideas that I had about song and singing and music as providing evidence of some kind of order in the afterlife, or some kind of harmony in the afterlife.

Your next book is going to be set in New Orleans and takes place at the height of the domestic slave trade. What about the topic felt worth visiting for you?

I used to listen to NPR all the time on my commute to New Orleans and, one day, as I was listening to NPR, I heard this show called TriPod. It was all about the history of New Orleans and, in one of the episodes, the journalist spoke about the history of the domestic slave trade in New Orleans and the fact that there were multiple slave pens around the city during the height of the domestic slave trade, but that there are only two plaques in the city right now that commemorate where those pens were, and one of them is in the wrong location. I think I was a bit horrified, but also a bit heartbroken. I started to tear up while I was listening to it, because I was thinking about the fact that that suffering had been erased, yet we live with the legacy of that suffering every day here in the South in the areas around New Orleans and in New Orleans. So I wanted to recall that. I wanted to bring that experience back into the light.

It will be an interesting counter to the conversation happening now surrounding Confederate statues.

Oh, yeah. Someone said on Twitter that they feel like the South, in some ways, won the war because they control what was commemorated, what was celebrated. I read that, and I totally agreed with them.

Sing, Unburied, Sing is available for purchase here