This Artist Has The Coolest Brooklyn Apartment You’ll Ever See

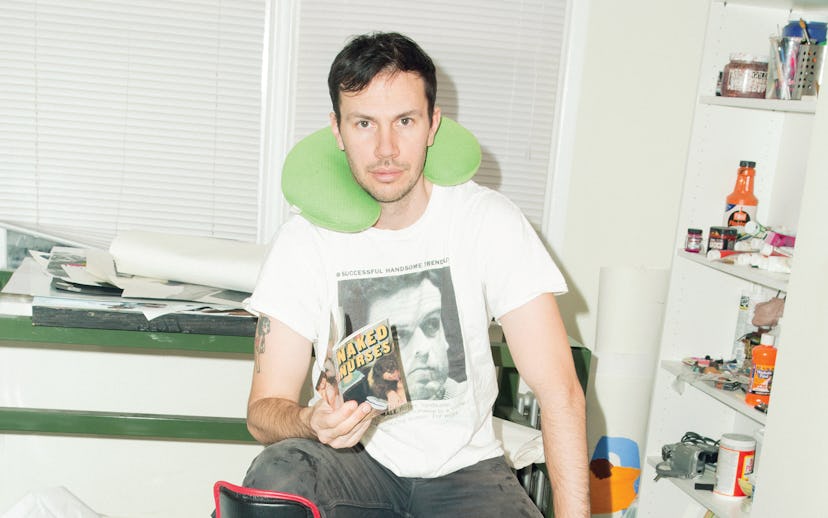

Homebodies: Judith Supine

The following feature appears in the April 2016 issue of NYLON.

Judith Supine has a paper problem. The artist, who works out of his apartment in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, makes collages of distorted figures from images he razors out of found fashion magazines, vintage porn, books, posters—anything he can get his hands on. Stacks of potential sources litter the floor, and cuttings of disembodied lips, hands, and torsos are scattered throughout his railroad one-bedroom, on counters, taped to the back of the front door, or stuck to the bottom of your foot. “It used to look like I was living in a dumpster,” he says, “but I’ve gotten better.”

To clear something up: Judith Supine is a guy. He assumed his mother’s identity years ago as a masked New York street artist to avoid getting caught for antics like wheat-pasting his work to building facades, buoying garish figures in the East River and a Central Park pond, and installing giant figures on a couple of the city’s bridges, including a neon-green lady smoking a cigarette atop the Queensboro Bridge in 2014. That stunt—accompanied by a dizzying YouTube video Supine made during the 4am climb—attracted the attention of the NYPD and Homeland Security. With the legal quagmire behind him, Supine now creates collages that are just as subversive—vulgar contortions and surreal morphing—but are more likely to be found in solo gallery shows in New York, Los Angeles, Miami, or London.

Judith the man has Judith the mom to thank in part for his creative expression. A child of few words growing up in Portsmouth, Virginia, he was encouraged to make art as a means to express himself. As a family, he says, “drawing and painting was our main activity.” Later he turned to printmaking, then collages. When he moved to New York about 12 years ago, he started photocopying collages into large-scale prints, affixing them to wood or canvas, painting them in signature fluorescent hues, and sometimes sealing them in resin. The image is continuously manipulated at each step, a characteristic of his distinct and recognizable style.

Despite the spontaneous nature of his process, Supine sticks to a daily routine. “I wake up at 6 or 6:30. I make peppermint tea. I put it on the coffee table. I meditate for 20 minutes. I drink my tea in the dark. I pet my cat and/or play chess,” he explains. Then he meets friends, goes to the gym, and starts making art by noon. “I eat the same things every day,” he notes. Lunch is cottage cheese, almonds, and blueberries. Breakfast is bacon and raw eggs. “I drink three eggs from a plastic cup,” he says. It’s quick. Dinner is usually steak and sautéed kale that he makes at home. At night he likes to watch a movie or read. James Ellroy, Elmore Leonard, William Blake, Henry Miller, and Céline are favorite authors. His cat, Emerson, hides behind the couch.

Sifting through the collages Supine is making for a billboard for The Armory Show in Chelsea, perhaps you could pick out some biographical influences, from his stints in Amsterdam, Costa Rica, Panama, and Thailand to his interest in crime novels, Muay Thai kickboxing, basketball, and soccer. But somehow it feels silly to seek interpretation from the artist’s stream-of-consciousness approach. Judith Supine speaks a language all his own.

Check out Supine's apartment in the gallery below.

When he was younger, Supine was drawn to printmaking, especially woodcuts and linocuts. “Gouging is so satisfying,” he says, “but it would take me two or three months to make just one.” He took to collage and realized he could make 10 in a day. “I started going through my neighbor’s trash and found stacks of magazines, like lesbian S&M.”

“When I make stuff, I treat it like my brother is my audience,” says Supine of Ian Kittredge, who is also an artist. “I’ll make 40 collages and will have to edit it down to four. He goes through them and tells me which ones he likes. I can get attached.”

Supine sifts through art in flat files in the kitchen. “I make stuff in the kitchen a lot, so I keep that area clean. I have a cutting mat on top of the flat file next to the stove, and I like to work there standing up. I listen to podcasts, like BBC’s In Our Time. It’ll be on, like, Aristotle,” he says, “or eunuchs.”

Supine also likes to draw the human figure. Not surprisingly, faces and forms are taped to the walls. “I have endless imagery,” he says. “I’ll get one base image and then go through thousands of images” to build it into a collage. “I have literally thousands of collages. I like doing collages”—which he copies into larger-scale works—“and I don’t like to sell them.”

Two toothbrushes commingle with the artist’s tools, which he washes in the sink. The foam brush he never uses, the wide ox-hair brush he uses a lot, and the detail brush he uses for tighter line work.

Artwork from friends sits around the apartment. After watching The Jinx, the HBO series about accused murderer Robert Durst, Supine’s friend Matias Schmidt, a painter, gave him a framed print of Durst’s handwriting. It appears in the haunting scene that all but proves Durst guilty.

Supine replaces the blade of his X-Acto knife often. “I might use 20 a day, like five an hour. I don’t know if it actually matters, but it’s like a fetish thing for me; I like having it very sharp. I’m obsessed with cutting shit and making lines exactly how I want them,” he says. Used blades on a kitchen windowsill will be folded into a piece of cardboard and wrapped with tape before they’re disposed of.