Entertainment

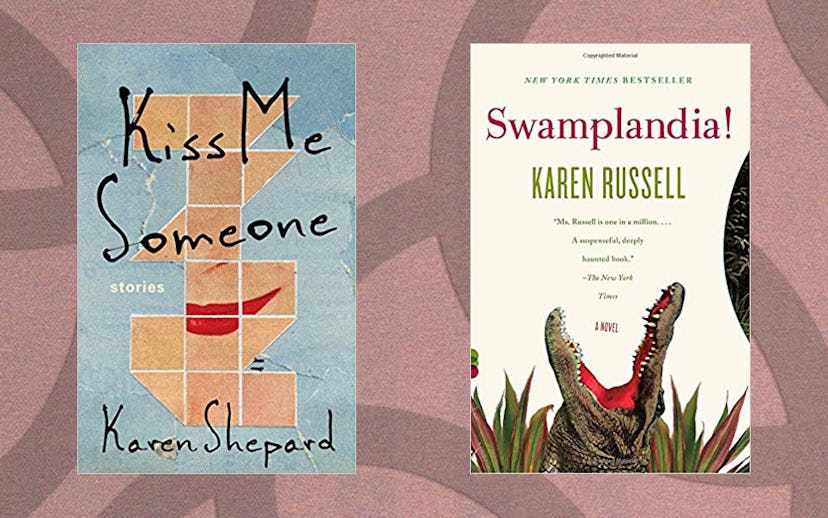

‘Kiss Me Someone:’ Karen Shepard And Karen Russell Talk About Shepard’s Brilliant, Darkly Funny Book

“Incest, 9/11, miscarriage, vehicular manslaughter—you’re thinking, now there’s a barrel of laughs”

Karen Shepard's latest short story collection, Kiss Me Someone, centers around women who exist in liminal spaces, the in-between. By writing about people who exist in the areas where boundaries blur, Shepard reveals uncomfortable truths about the ways in which we live our lives, what things we're responsible for, and how we try to absolve ourselves and others of misdeeds. Below, Shepard talks with author Karen Russell (Swamplandia!, Vampires in the Lemon Grove) about Kiss Me Someone, unlikable characters, and how to make a funny story when it deals with horrific things.

KAREN RUSSELL: Once, you joked to me that the title for this collection should be Sad People Having Creepy Sex. Want to tell us more about this working title, and why it felt apt? How did you decide on Kiss Me Someone as the ultimate title for this collection?

KAREN SHEPARD: What do you mean ‘joked’?

Actually, the title was Sad, Angry People Having Creepy Sex. A small difference, but it’s the terrible combination of sad and angry that makes people sabotage themselves, I think. A lot of us would sell our souls not to feel sad, but without the anger, we might not place the call to the devil. There’s something passive, though utterly debilitating, about sadness. Anger is all about abandoning passivity. I was interested in how far people will go to stop feeling sad and angry. Will they hurt themselves? Will they hurt others they care about? And if they will, what stories do they tell themselves to live with themselves after those choices?

The current title occurred to me when I was rereading Paula Fox’s brilliant Desperate Characters. In it, a character goes to make a secret phone call at a Brooklyn payphone. Written on the wall is: Kiss Me Someone. The phrase spoke to me about the way need and demand come together. There’s something plaintive and aggressive about the phrase. Sad and angry. And of course, kissing “someone,” i.e. some anonymous anyone, is often a recipe for creepy sex, and then you’re back to sadness and anger. The good thing about the original title is that I’ll probably be able to use it for any book I write. A friend of mine once said she was going to start her own twelve-step program: Adult Children of Parents.

KR: Speaking of creepy sex, one of my favorite stories, “Fire Horse,” features a sex scene between a brother and a sister. (“This was eating chilies right off the plant. This was silencing a room.”) The scene is unforgettable and disturbing, and yet it isn’t sensationalized, and it doesn’t overwhelm the story. The power seems to come from our comprehension of the welter of pain and rage and love acting on the narrator, but also from our knowledge that she knows what forces are driving her, and is unwilling or unable to stop. I see this pattern a lot in your work. We feel the excruciating tension between a character’s self-awareness and her inability, or unwillingness, to break a pattern, to pull up on the controls, to save her own life. The inertia of self-destruction.

You design stories that give us a context to understand why some pretty messed up stuff happens—the landmines of a history that spans generation, the animatronic violence of family. But these people aren’t sleepwalkers. You always hold your characters to account for the actions they take. What role does self-awareness play in these stories?

KS: Putting my characters on the hook is crucial to my fiction. As Toby Wolff has said—and I may be paraphrasing here, “Other than very small children, we are all, in some way, responsible for the situations in which we find ourselves.” I’m much less interested in what I sometimes call “obstacles overcome” fiction; the fiction where a very well-intentioned, good-hearted, completely likable protagonist deals with the obstacles that the world throws into her path. My fiction is almost always about what we’ll do or not do despite, or perhaps because of, our perceptive abilities. This may explain my sales figures. I’m always trying to explore the relationship between self-awareness, perception, and accountability. I’m sure there are deep and dull psychological reasons why this is such a focus of mine, but I won’t bore you with my ruminations on those reasons here. I will say that I’m sure being married to Jim Shepard has pushed me even further in this direction. Jim’s fiction is all about holding characters accountable in ways that they refuse to hold themselves. He has a collection called Like You’d Understand Anyway that’s filled with self-sabotaging male characters surrounded by female loved ones who are way more emotionally healthy than they are. (Autobiographical? You make the call.) I told him I was going to write a companion collection from the point of view of all those women, and I was going to call it: Try Me.

KR: Flannery O’Connor said that a short story sets out to explore the “mystery of personality.” Which of the characters in Kiss Me Someone is the most mysterious to you? What did you discover about them that surprised you, while writing out the story? What continues to mystify or confound you?

KS: You should imagine me living in a constant state of mystification and bafflement. Imagine a blind woman moving her way down a dark hallway. Are there people who don’t live this way?

I guess, on some level, all my characters are always mysteries to me. I hope they’re less of a mystery by the end of the story or the novel, but if they’re complicated enough, there will probably always be aspects of them that I’ll never fully understand. And that’s a good thing. We spend so much time in our lives convincing ourselves that we know enough: enough to get good grades, to do our jobs well, to comprehend our politics, etc. For me, writing serves as an exploration of what I don’t know, and a reminder that not knowing is actually a pretty useful state to spend some time in. Can you imagine if I told you that right now you know your spouse, or your child, or your best friend as well as you will ever know them? Wouldn’t that be kind of horrifying?

On the other hand, most of these stories started in one way or another by my posing the simple question to myself: Can you imagine? This question is, obviously, an expression of mystery. Two of the stories are perhaps extreme versions of that question. One is “Girls Only,” in which a group of college girlfriends have to confront the fact that they didn’t protect one of their own when she may have needed it most. This story began when I heard a similar, though actually much worse, story from a friend about two roommates who did nothing while a third roommate was being stabbed in her bedroom. How did those two girls live with themselves? I thought. What stories did they need to tell themselves to go on? In the fiction, I had to tone down the behavior; an example of life being too unbelievable for fiction. But the central question was about the mystery of their behavior, and I was also, of course, interested in asking myself whether I could empathize with behavior that seemed incomprehensible. The same was true of the story, “Rescue,” which is based on a hit-and-run accident that happened in the small New England town where I live. I thought it was a story about how someone could hit someone and leave her in the road. Andre Dubus’s brilliant “A Father’s Story” explores a similar issue; if you haven’t read it, go out and do so immediately. Of course, “Rescue” ended up also being about the consciousness of a small town, about the collective story a town tells itself when something terrible happens within it, and if you’re talking about a New England town, it’s not too long before you get to issues of race and class and what role those things play in those stories we tell ourselves. So, to some extent the mysteries at the heart of those stories are still mysteries to me, but that is true, I hope, of all my stories. So, there’s a tag line that the marketing department will love: Read these stories and be as confused, perhaps more confused, than you were before.

KR: Incest, 9/11, miscarriage, vehicular manslaughter—you’re thinking, now there’s a barrel of laughs. But I found these stories to be some of the funniest I’ve ever read, often in direct proportion to how dark and deep they go. (From “Light as a Feather”: “Her mother turned out to be a different person: no longer the self-sufficient narcissist and now an anxious, fluttery and dependent narcissist.”) What role do you see humor playing in your stories?

KS: Well, it’s pretty cool to hear that Karen Russell, one of the funniest people I know, thinks these stories are funny.

I don’t use humor nearly as often or as well as someone like, say, Jim Shepard does, but it is important to me because of how humor is related to perception. You have to be aware to be funny; you have to have perceived the world around you well enough to get outside it enough to describe it accurately, and, and this seems crucial, change the tone of your approach to that world. Too much earnestness is the death of awareness and growth, I think. Humor allows you to create more self-consciousness, more awareness by way of a tonal shift, which gets you outside of yourself and the world enough to return you to it better, different. As Dickinson said, “Tell all the Truth, but tell it slant.”

KR: Joy Williams makes the claim that “a novel wants to befriend you, a short story almost never.” She talks about a certain coldness to the short-story form. Before Kiss Me Someone, you published four novels. I wonder if you can talk about the difference in how you approach the two forms and how you know which is appropriate?

KS: I’m often told by readers or reviewers that my characters are unlikeable. Once, at a book club, the opening comment was, “Would you like to hear what I really didn’t like about these characters?” So, to some extent, I would say that neither my novels nor my short stories want to befriend you. (My publicist is hanging her head.) If literature is all about expanding our empathetic abilities, I’m most interested in doing that for difficult characters, characters who are most like the people we actually meet in the world: people who are flawed, sometimes deeply flawed. It’s easy to empathize with saints; it’s harder to empathize with sinners, but don’t we all have a little bit of both in us? My story, “Don’t Know Where, Don’t Know When,” came out of my impatience with the Portraits of Grief series that the New York Times ran after 9/11. All those tiny narratives about victims’ lives painted each and every one of them as saints. Surely, I thought, there were people among the thousands who died who were not so saintly, perhaps even pretty horrible. Why do we feel like only the saintly can be mourned? So I wrote a story about a pretty horrible guy who dies on 9/11 and the way in which his wife and mistress try to figure out how to mourn him. The writer Uwem Akpan has said that “Literature allows us to sit for a while with people we’d rather not meet.” I couldn’t agree more. I don’t have to marry the guy from my story, but I think I’m better off if I try to understand him.

KR: Even though these are superficially realist tales, they engage with so much darkness and magic. Women cast spells with their bodies to get what they want; they also excel at a kind of self-hypnosis. And then I found myself thinking, These are also ghost stories. They are haunted by the past: Ex-boyfriends turn up, old transgressions get exhumed, memories resurface like galleons, China eclipses America, past youthful selves resurface inside of adult women with hungry red mouths. Were you thinking about ghosts, when you were writing these stories? What do you see them as being haunted by?

KS: Oh, I love this way of looking at the stories! And leave it to Karen Russell to see them this way. Karen’s thinking: Where are the werewolves? Where is Bird Man? There must be some way to see these stories as something other than the banal, realist tales they seem to be….

In, “On Keeping a Notebook,” Joan Didion tells us that it’s a good idea to stay on “nodding terms” with our former selves. She says if we don’t, they turn up “unannounced and surprise us.” Didion is suggesting that if you don’t recognize who you were, you end up being in thrall to those former selves, at their whims. For me, being haunted is certainly about that, but it’s also more positive than that. I want to be haunted by former versions of myself, by places and people, real or imagined, who have mattered to me. That’s my way of keeping all those selves, places, objects alive. And isn’t that what all our stories are, a kind of ghost story? A kind of weird alchemy of the real and the imagined that takes us out of our world for a while, only to return us to this world somewhat shape-shifted and adjusted? Literature as a really good séance. Or chiropractor.

Kiss Me Someone is available for purchase here.