Entertainment

How Complicit Are We In An Artist’s Self-Destruction?

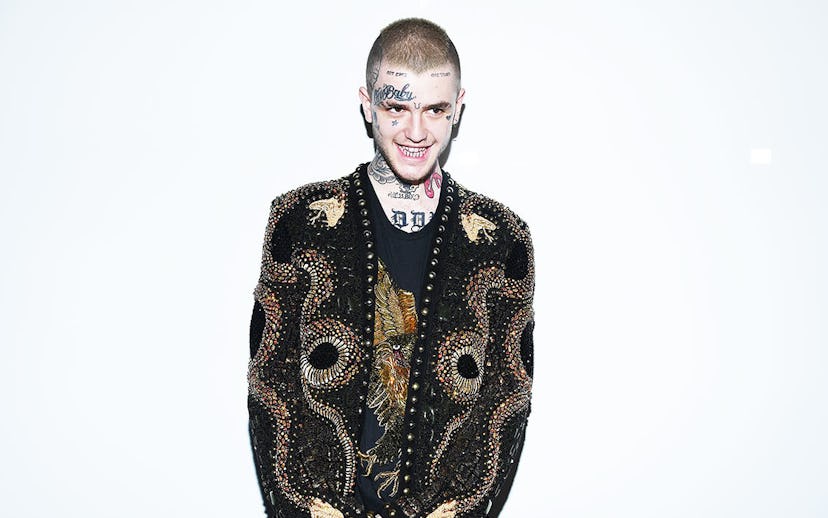

The death of Lil Peep highlights how mental illness is still stigmatized in the music industry

Gustav Åhr—aka Lil Peep—is dead. He was 21 years old. It's suspected an overdose of bunk Xanax is to blame. Peep's death isn't just tragic, it's infuriating. It's sobering. It's unfair. It's fucked-up. Peep was breaking new ground fusing emo together with hip-hop and trap. In the time leading up to his debut album, August's Come Over When You're Sober, Pt. 1, he courted over 1 million followers on Instagram and millions on millions of Spotify streams. He was the new kid on the block to watch, and now he's not—because of mental illness and the way he went about treating it. It's a goddamn shame.

As the eulogies begin to hit the airwaves, let's not forget what's to blame here. I've seen enough reactions to Peep's death blaming him for his drug addiction. It's not Peep's fault. It never was Peep. It was mental illness. A recent study says musicians are three times more likely to experience depression, anxiety, and panic attacks than the general public. Peep has never shied from discussing his mental illness. It's written all over his music. ("Everybody telling me life's short, but I wanna die," Peep says on "The Brightside.") The drug use we witnessed through his Instagram and lyrics wasn't glamorous like The Weeknd's. It wasn't something to dance to. It was medicinal more than it was recreational. And yet, we partied to it.

The signs were all there: his pain, his emptiness, and his need to fill that void. Peep's manager, Chase Ortega, tweeted that he's been "expecting this call for a year" following the news of Peep's death. At what point does escape become a concern? When does someone's music and social media presence become distressing instead of entertaining? How do we remain complicit watching artists destroy themselves?

Music has a deceptive way of glamorizing drug abuse. I can't tell you how many times I listened to early Weeknd material, imagining myself as uninhibited and chemically romanced as he and his crew were. His use was (and is) an escape into a world I know myself too well to ever get caught up in. Peep's music functioned in a similar way, only now, in light of his death, it doesn't. Instead, his death has opened our eyes to the other side of Peep's reality, the one many of us chose to ignore in favor of entertainment.

Good music and bad habits go together. I don't know where we go from here, aside from having difficult discussions about the intersection of music, mental illness, and how we enable it—even when it's clearly destructive. Let's not let Peep's death be in vain.