Entertainment

A Beautiful, Strange New Book Shows Why Horse Girls Aren’t Easy

Talking with Lisa Hanawalt about ‘Coyote Doggirl’

"What I'm always worried about with every new book," Lisa Hanawalt tells me, over the phone, is "if it's the one where people will realize that I'm bad."

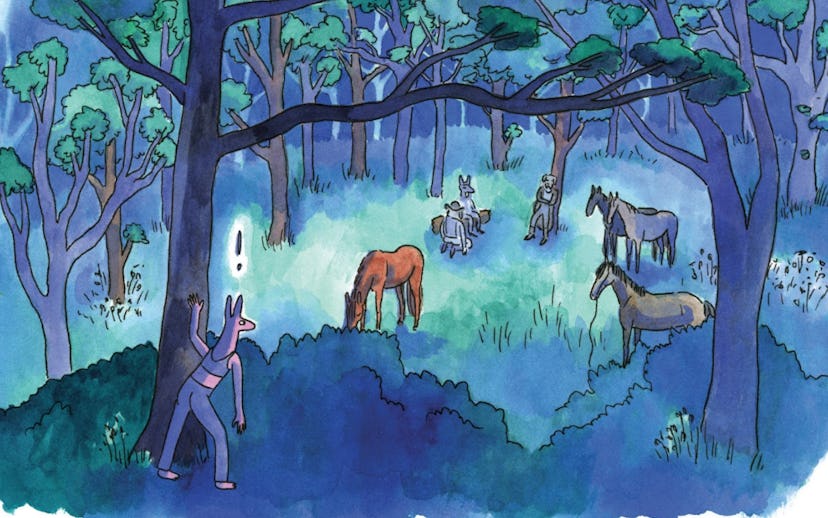

Hanawalt, of course, has nothing to fear; the writer and illustrator's latest book, Coyote Doggirl, is a specifically strange, beautiful, sad story about a girl and her horse, and about the expansiveness of love and the unlimited possibilities present once we allow ourselves to be less alone. And it's even further proof of Hanawalt's peculiar genius, her ability to access difficult truths in the most absurd ways possible.

With her latest work, Hanawalt operates within a familiar world—the Old West—but plays with and subverts the most commonly held Western tropes, in order to tell the story of an archetypal loner, sort of an ur-horse girl, and her trusty equine companion. It's a story of friendship, revenge, loss, and discovery, and it is experienced visually as something akin to reading a long sunset, replete with watery pinks and aggressive yellows and golds. It's also funny and rude and, you know, really not for children. Instead, it is for anyone who occasionally wants to tell everyone they know to fuck off, but also wants to be taken back in their embrace once the anger fades. It's for anyone who's ever wanted to ride off into the sunset. It's for anyone whose insides have ever felt sunburned. It's for anyone, really.

Below, Hanawalt expands on the idea behind the book, why horse girls are not so different from outlaws, and how "following her North Star" takes her to some unlikely places.

What was the idea behind this book?

It really just started as a very sudden, stream-of-consciousness idea, about the relationship between horse and rider. I'd gone on a little vacation upstate in New York, back when I was living in Brooklyn. And me and my boyfriend went on a horse ride, and I rekindled my obsession that I'd had since I was eight years old. And I'd been watching all these Westerns, too. I'd been watching all these Sergio Leone movies, and John Ford, and True Grit. And so it all kind of came together, and I was like, Oh, I'm going to subvert the genre a little bit and just have the rider exclusively acknowledge the horse while they're running away from the bad guys. And then it just very organically grew into a longer story, and I realized, Oh, this could actually have an arc to it. And I just sort of slowly worked on it between other projects over the next few years. And at times I would come to it, and I hadn't looked at it in a year, and I'd just think, Oh my god, what is this mess. And I just slowly tidied it up, and I almost tossed it in the trash at one point. But I didn't, and then I finally finished it.

What's your process for creating a book like this, where the interplay between text and illustration is so calibrated? How much do you have planned out?

I mostly write before I draw, but it's really an erratic messy mishmash, as far as how I work. I sketched the drawings of [Coyote Doggirl] and thought, Oh, this is a cool character. And then I wrote out some thoughts about horses. And then that became a dialogue. And then I sketch a lot of rough drafts of how the panels and images will fit together on the page, and then I adjust the writing again, and kind of comb through it a few more times. I wrote out what I wanted to happen, like, knowing she needs to get back to her horse at some point. How is that going to happen? What's going to get her there? I had a version of this book that was closer to 300 pages, and I was like, Well, I'm never going to finish that with my schedule, so let's tone it down and fix the pacing. It's very organic, I'd say. I'm not a good planner.

It's interesting because whereas a novel could maybe have some throwaway paragraphs or scenes, for something like this, nothing can feel unnecessary. Everything feels so deliberate, so taut and specific.

There's a lot of little tidbits in this book that don't necessarily fit in the main story but that I feel are important for pacing and for character development. So for me, it's not like, "Oh, there need to be five of those to balance out the story." There's no map to it. It's kind of reading it over and over again and thinking, like, Does this feel good or does it drag or whatever. It's kind of a gut feeling for me.

In the book, you have these two archetypes meeting, one is this classic "horse girl," which is such an adolescent girl stereotype, but here, she's meeting up with another archetype, the outlaw, who is such a masculine figure traditionally. But even though they superficially feel different—the naive girl and the grizzled old man—they actually kind of exist along the same spectrum, because they're often loners who are just really into horses. And they're pretty tough.

Oh, yeah. Horse girls are tough. [When I rode,] I got tossed around so much. I got stepped on and bitten and kicked in the ribs and tossed around. It was so physical!

Yeah, and it's a solitary pursuit. Or, you're alone as a person, but you're also with this horse. So there's that tension of existing alongside another living thing, but not being able to communicate. It's kind of liberating.

For her, it's a way of life.

How did it feel to create this character, who lives so completely on her own terms?

She's really personal to me. A lot of things about her, I sort of wish I could be. I wish I had wilderness survival skills, so that's all just fantasy. I wish I was really good at riding horses, but I'm not that good. I wish I was better at riding out alone, but I ride with other people, because I'm kind of scared, because horses are dangerous. She's very self-reliant in a way that I admire, but then she's very flawed and actually, over the course of the book, she finds that self-reliance is not her number one goal in her life. Because through her journey, she's met all these other people who have helped her along the way, and her values have changed a little bit. Throughout my entire life, I've been like, I just wish I could be a cold bitch who could get along on her own and never need other people's help. And then I've learned that you actually do need other people's help, and learning to ask for other people's help is actually one of the most important skills you can have in life. [And then, also,] I like how silly and goofy she is. She's kind of rude. She looks sunburnt and vulnerable. I don't know. I kind of like characters who are kind of ballsy and brusque but also clearly vulnerable.

I love her rudeness. I love when she's lying down on the back of her horse giving these wolves, who have come to her aid, the finger.

She's so rude!

She's so rude. It's so liberating.

Those wolves are trying to help her, but she's so rude. She's sort of the worst, but they kind of embrace her in spite of it.

When you're writing, do you ever think about the audience that will eventually read your work? Does that ever influence you?

I try and follow my North Star of what I find interesting and funny and beautiful and sad at all times, and then worrying about what the audience thinks later. Because if I worry about that first, I would find it a little paralyzing, and I worry it would make my work a little boring. At one point, my mom was reading some early pages, and she was like, "You know, if you clean up the language of this a little bit, it could be for children." And I was like, "I'm not interested in that." I know that, and I know that could expand the audience, but it's just not what I'm interested in, and I have the extreme privilege of not having to worry too much about that with this book. This book is just 100 percent what I want it to be. There's a part in this book where I write the words "big, perfect, purple pussy lips" or whatever, and I was just like, This is such a weird, weird thing to put in here, but I just couldn't get it out of my head as something that I wanted. I find it shocking in a really weird way. And so I kept it in there. I know it's going to limit the audience, and most of my work has a limited audience for that reason, but I'm fine with that.

I love that purple pussy lips are your North Star.

In some ways, I feel like I'm just a plant spewing seeds out into the world, and I feel like it's sort of selfish. You know, whoever picks up those seeds and finds them interesting or whatever... this analogy is kind of falling apart, but the thing is, you know, I find my audience.

Coyote Doggirl is available for purchase here.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.