Entertainment

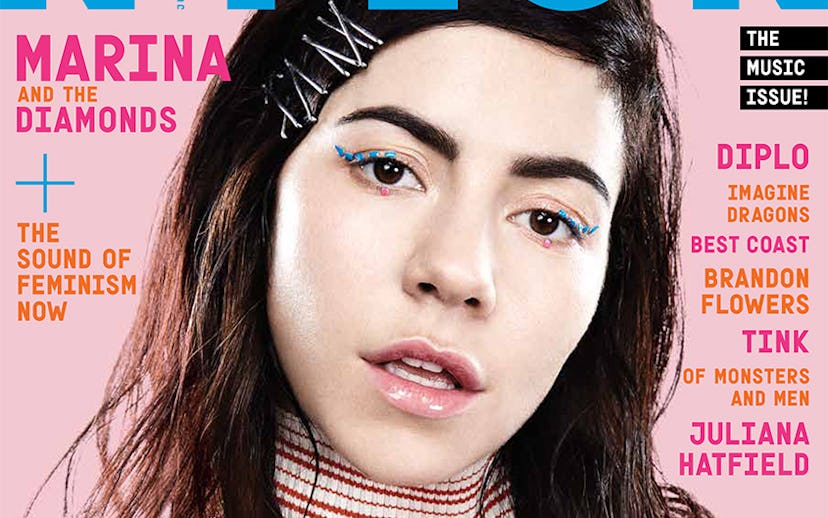

you can’t pin marina + the diamonds down

read our entire cover story

"Can we do one more?" asks Marina Diamandis, poised behind a neon microphone stand. The singer-songwriter, better known as Marina and the Diamonds, is taping a musical segment for Conan. The ginger-coiffed host isn’t around, but the room is nonetheless buzzing with staffers, one of whom balances on a ladder by the backdrop, fiddling with the moon.

Diamandis has already recorded two versions of “Forget,” an arresting, mid-tempo confessional from her new album, Froot (out now on Neon Gold/Elektra), but she’s not entirely satisfied: Her vocals—sensuous and intoning—were perfect, but she neglected to move very much at first, and was only starting to loosen up on the second go-round, holding the gaze of the camera and undulating her arms to the line “Ever since I can remember / life was like a tipping scale.” The crew honors her request, and a hair-and-makeup team rushes over for one last pat, pluck, and spritz.

Third time’s the charm. Diamandis comes alive, swiveling her military-grade abdomen and pulling the neon stand to her side with a relaxed swagger. She looks pleased to have nailed it, not only because this is one of her first U.S. television spots in support of Froot, but also because, in some respects, this is a new style of performance for her.

On the last Marina and the Diamonds album, 2012’s Electra Heart, the singer affected a pop-star persona that she fully committed to: With a platinum wig and bubble-gum-pink pleated skirts, she practically took to the stage skipping. Froot, on the other hand, is a ripe, beautiful, and achingly sincere album. “It’s a big jump,” she says later. “I’m coming to grips with being OK just standing still for a song.” Today, the 29-year-old looks nothing like her former alter ego, in a copper-colored leopard-print pantsuit and black bandeau, her thick brunette hair falling in natural waves around her shoulders. She smiles and thanks everybody as she heads back to the dressing room, but not before obliging a lucky audience member. Even in the middle of the day, midweek on the Warner Bros. lot in Burbank, California, Diamandis has a die-hard fan—a teenage girl who played hooky so she could deliver a handwritten letter in person. Trembling, she says, “You’re just the best. I tell my friends: ‘Marina is the only artist I listen to.’” She secures no fewer than three hugs and several pictures, which is not unusual—the Diamonds, as the singer calls her fans, are a devoted bunch, and she engages them on a level that few artists do.

She can also relate. Last night, after one of Britney Spears’s residency shows in Las Vegas, Diamandis met her teen idol—for about 15 seconds. “Dizzy and nauseous,” she replies instantly when I ask how she felt then. We’re making a beeline for the high-end Brookstone massage chairs in the Conan greenroom, which are capable of full-body Swedish treatments. Diamandis describes Spears as “shy,” and speaks with the faintest regret that the circumstances were so artificial. After a minute of conferring over whether the machines are grabbing our calves a bit too firmly, she admits: “It’s awkward—it would be different if she knew my music, and we were meeting as artists, you know?”

But the timing of her introduction to Spears is uncanny, considering the pivotal juncture that Diamandis finds herself at now: As the titular character from Electra Heart, she came closer to the orbit of the “…Baby One More Time” singer than ever before, working with bigwig co-writer/producers such as Diplo and Dr. Luke. “I was like, ‘Am I going to pull this off if I just go and work with this guy?,’” she says. “That’s what I was interested in exploring. And it bloody well did get me on the radio. I had a certain level of success, where it was about to tip, but it didn’t quite.” Electra Heart, her sophomore effort, entered the U.K. charts at No. 1, but moved just under 150,000 copies in the States. And if the intent was to subvert the vapid and corrupting influence of stardom, even Diamandis admits the distinction got blurred. Her collaborators were credible people in the industry, “but they just didn’t really understand what I was trying to do,” she adds. “And I was responsible because I was on the fence as well.”

In that regard, Froot is more than just her third album: It’s a statement of intent, a record written entirely by herself, and an official kiss-off to the hit-making industrial complex. “It’s great to have Rihannas and Katys, but you also need people who are really purist and idiosyncratic,” she says. “This is a lifetime record for me. I don’t think I’ll do something of this ilk again.”

Click through the gallery to read the entire story.

“Are you satisfied/ with an average life?” sang Diamandis on the opening track of her 2010 debut album, The Family Jewels—making it clear by the question that she was not. Growing up in the small town of Pandy in southeast Wales, where recreation meant either the pub or the sweet shop, Diamandis never dreamed of going into the music industry. She didn’t sing, she recalls only a fleeting awareness of Madonna and Gwen Stefani, and besides, it just wasn’t what people in Pandy aspired to.

Eventually, though, her mom got cable, and Diamandis discovered the video for “Oops!...I Did It Again.” By age 19, the straight-A student was determined to become famous—thus the auditions for The Lion King and an all-boy reggae band, now a cornerstone in the Marina legend. (It’s just as well that didn’t pan out, because, aside from the logistical problems, they were never heard from again.) Eventually, her priorities shifted, and Diamandis took control of her own fate, attending no less than four universities to study vocal training, composition, and keyboards, but always dropping out before too long—much to the chagrin of her “academic-minded” father, she says.

Of this scrappy, ambitious period, Diamandis has said that she “happily sacrificed” friends and relationships. “I really felt like the two couldn’t coexist, but perhaps that was an excuse for the fact that I had a bit of a social anxiety disorder,” she says. “Any time anyone would ask me to hang out, I would say no. Publicly, I felt completely comfortable, but having a meaningful conversation would panic me.”

It’s a week after the Conan taping, and we’re walking the grounds of Los Angeles’ Griffith Observatory. Diamandis is dressed down, in blue culottes, a chambray shirt, and Converse sneakers. It’s a gray and overcast Thursday, though it’s still green to the singer, who has synesthesia and associates days of the week with colors. She pauses to note that the landscape here reminds her of Greece, her father’s native country, where she lived for two years following her parents’ divorce and where she first felt the urge to write, inspired by nothing more than a desire to communicate.

Success came relatively quickly: In the spring of 2008, just three years after she had left Greece for London, the 22-year-old Diamandis was playing a sold-out show at Hoxton Square Bar & Kitchen in the south of the city with fellow up-and-comers Gotye and Nick Mulvey. It would be the gig that helped get her signed to Elektra/Atlantic Records. “She had this amazing voice and incredible personality, but she was trapped behind the keyboard,” says Derek Davies, a longtime friend and co-founder of Neon Gold Records, who was in attendance, and soon after released the first Marina and the Diamonds singles Stateside. “It wasn’t until a year later, when Atlantic was able to put a band together for a proper gig, that she was able to step into the spotlight and become the star that she is.”

Diamandis and I head inside and find a seat in the Observatory’s café. She is eye-level with the Hollywood sign, just a short distance away, which also happens to spell the name of one of her first-ever singles, a sassy criticism of the homogenizing aspects of the film industry. She enthusiastically pours French vanilla creamer into her coffee as I try to recall the lyrics, “Oh my god, you look just like Shakira / No, no, you’re Catherine Zeta / Actually, my name’s Marina,” which she sang with all the confidence of someone destined for one-name notoriety.

In many ways, Froot feels like the natural follow-up to Family Jewels, except that her debut captured the yearning of a woman fresh out of her teens, and Diamandis is now on the precipice of 30 (which she’s excited about, for the record). Her focus turned inward and she tuned out the ticking clock of her label, which wanted to harness Electra’s momentum by delivering another album quickly, because she thinks of her music as “documenting a life,” and she needed some time to actually live.

Like Electra Heart, the new album is partially about a breakup—this time of her longest relationship yet (two years)—though she’s coming at it from the other side. “With Electra Heart, I was definitely the heartbroken,” she says. “With Froot, I was the…ender. It’s a relief putting it into songs, but with Electra I loved it, because I was like, ‘I hope he fucking hears these songs!’ Whereas with this one I was like, ‘I hope he fucking doesn’t.’”

When she was ready, she sat down with British producer and self-proclaimed egghead David Kosten (Bat for Lashes, Everything Everything) in his recording studio in London. “I told her I wanted to make a record that says, ‘Back off, motherfuckers,’” says Kosten, via phone. “Something that is hopefully untouchable in a creative way. She liked the idea, and that line—‘Back off, motherfuckers’—is immortalized in song now [‘Can’t Pin Me Down’].” Diamandis sent Kosten rough demos that he says “sounded like they had been recorded down a deep well,” and over generous amounts of greasy food from nearby Portabello Road, “we made an album paying homage to Pat Benatar or Like a Prayer-era Madonna.”

One of the standout tracks is the brooding burn number “Better Than That,” which takes shots at a woman who may have had a dalliance with the singer’s ex. Following some lyrical bread crumbs, fans have speculated the song is about another chart-topping British artist, and Diamandis lets out a hearty laugh when I ask her about this. “It’s about a human,” she replies, recovering. A human who’s alive? “Yes. It’s just calling facts on somebody.”

Gossip aside, the bridge features the surprisingly melodic line “I’m not passing judgment on her sexual life / I’m passing judgment on the way she always stuck her knife,” a bold feminist statement, powerful in its negotiation of the twin temptations of outrage and degradation. “It obviously has some anger in it, but I want to make clear that I’m not slut-shaming,” says Diamandis.

We get up to walk around and cruise past an exhibit on the moon’s phases, where just moments earlier a tourist had been challenging her baffled atheist nephew on the existence of God. (“Who do you think keeps you alive then?” she asked. “Modern medicine,” he replied.) The exchange recalls the best song on Froot, at least in my (and Kosten’s) opinion: “Savages,” a propulsive, poetic, synth-driven track that builds to the trenchant refrain “I’m not afraid of God / I am afraid of man.” Though it was specifically inspired by the Boston Marathon bombing, it could easily be the catchphrase of our troubled times. “I think there is a universal energy that we’re all a part of,” says Diamandis when I ask about her own beliefs. “I’m interested in human nature and what decides for each person whether they are going to be good or bad. Because we’re all capable of both.”

We head into the planetarium to watch a light show about the aurora borealis, a.k.a. the northern lights, when the sky at the pole is infused with brilliant shades of neon green and purple. The Vikings mistook the lights for a fire bridge built by the gods, but they’re actually the result of a collision between the sun’s charged particles and the Earth’s magnetic field. Right? “I was concentrating on the visuals,” says Diamandis, laughing. “I’m wondering if I could put on a show here.”

In October, Marina and the Diamonds will embark on the Neon Nature tour. She says the idea was “to blend something artificial and something natural, like you do with your digital and your real life.” Audiences will catch glimpses of what’s to come—purple Astroturf, giant inflatable fruits—when she hits the festival circuit this summer, including high-profile stops at Sweetlife, Governors Ball, and Lollapalooza. “I want this year to be massive and to have an amazing tour,” she says.

At an industry show hosted by Pandora a few nights prior to our Observatory visit, Diamandis didn’t yet have any of these accoutrements, but a helpful Diamond handed over a watermelon-printed fan, which she utilized during the coyly confrontational old-school number “I Am Not a Robot.” There were about 100 audience members in total, including a YouTube sensation and an AFI frontman (Joey Graceffa and Davey Havok, respectively). And somewhere among them were the young women who write Diamandis lengthy letters in multicolored ink, proving their cred by name-checking unreleased tracks and saying things like, You were the main reason I became a feminist and You were the only one who seemed to understand how it felt to be really depressed.

“Marina’s songs are so moving and intensely personal that they may impede universal commercial appeal,” Davies had told me, “but they foster an intense relationship with the listeners.” Diamandis understands this, and creates a world for her admirers to step into, full of tactile objects and DIY possibilities—much like the baby barrettes and candy necklaces of a generation prior, except now it’s homemade fruit headbands and Technicolor face paint.

As the sun sets on our day at the Observatory, I realize Diamandis has more in common with its founder, Griffith J. Griffith, than just their Welsh heritage. Griffith donated the land and commissioned the building, believing that “if all of mankind could look through that telescope, it would change the world.” Diamandis certainly shares this for-the-people mentality. Running contrary to the surprise-album strategy that has become almost routine for major artists, she created the Froot of the Month club, releasing one song per month beginning in late 2014 and leading up to the album’s release this past March. It was an unorthodox and single-forgoing move that allowed her fans to be part of the album’s era—after all, for many of them, six months can mean the difference between a learner’s permit and a driver’s license. And it worked: People still bought the record, and it entered the Billboard 200 chart at No. 8.

Lately, though, Diamandis has also been thinking about life after the Neon Nature tour. “To do this kind of job, you have to have a certain level of self-interest, to work toward the common goal of you every day,” she says. “And that’s great when that’s all you want. But I think I want other things now.” What those other things are she isn’t sure. At the moment, it’s a glamping trip to Yosemite with her “special person” this weekend. But as to whether there will be another album in two years? Five? She can’t say. “I feel very satisfied,” she says. “I don’t know if I want this to be the focus of my life anymore. I badly need to be stimulated by other things now.”

Rest assured: She isn’t giving up music or her Diamonds. In fact, if anything, she’s thinking about how to better connect with them. “I’d way prefer going to schools and doing talks and engaging people in debates than touring for the rest of my life,” she says, ruminating out loud. Her 20-year-old self would be impressed by what comes next: “It’s actually just really nice to have normal conversations.”