Entertainment

A Stunning New Memoir Confronts A Complicated Legacy Of Addiction, Love, And Loss

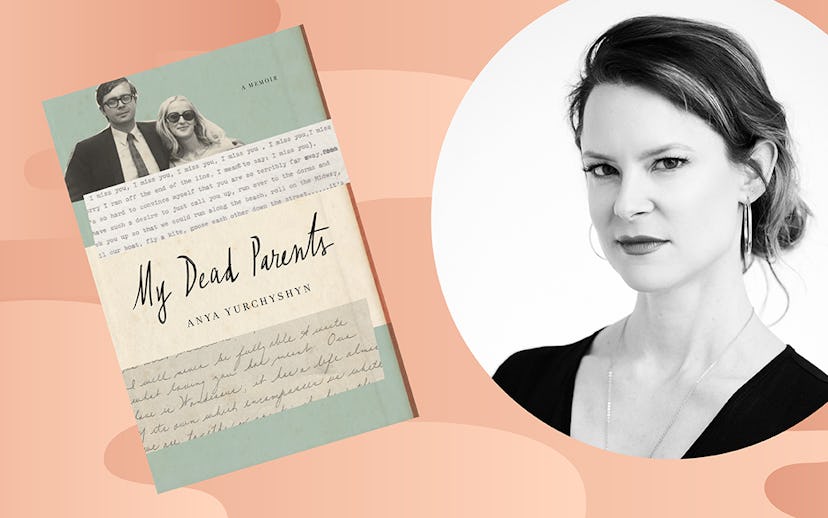

Talking with ‘My Dead Parents’ author Anya Yurchyshyn

"The experience of losing our parents is going to be universal regardless of what our relationship is with them," Anya Yurchyshyn says to me over the phone. "There's a process of going through someone's most personal belongings that will always reveal something about them that you didn't know, or will force you to see them in a new way. And that both can be very jarring, particularly when you think you know them well, and also really wonderful."

Yurchyshyn knows well of what she speaks. By the age of 32, she had lost both her parents—first her father in a car accident when she was just 16, and then, 16 years later, her mother, of chronic alcoholism, following a long period of addiction and illness. Yurchyshyn had a complicated, tumultuous relationship with her parents—individually, and as a unit—but it was one that she couldn't help but explore in the period following her mother's death, as she sorted through the chaos of her family's once-treasure-filled house, and found photos and letters indicating that there was much more to her parents' lives than she had ever realized.

The result of this exploration is the searing memoir, My Dead Parents, in which Yurchyshyn grapples with the legacy she inherited from her mother and father, uncovering long-held secrets, and confronting a truth that so many of us refuse to acknowledge for much of our lives: Our parents are people too, separate from their relationship to us.

Below, I speak with Yurchyshyn about the memoir, the difficulties of having a family member struggling with addiction, and how to avoid getting trapped in the past, no matter how compelling it is.

One thing that really impressed itself upon me when reading My Dead Parents was how honest you were about yourself and your own emotions and sometimes your lack of, not emotions, but the kind of emotions that other people thought you should be having, like when you weren't filled with grief [after each of your parents died]. Was it difficult to be honest about that?

The short answer is, it was very difficult. It was really important for me to be honest, but I knew that certain things I was saying—for example, what you pointed out, not only was I not sad when my father died, I was relieved... [But] I had begun working on an anonymous blog of the same name, and the anonymity really let me say whatever I wanted, and I didn't have to worry about my family finding it or strangers tracking me down to tell me that they thought what I said was offensive or that it was messed up or, you know, that I needed more therapy. And the next step from that was writing this BuzzFeed essay, that ended up getting a lot of attention and leading to the book deal, and publishing that essay and attaching my name to it for the first time was really terrifying but also ended up being really wonderful because I did own those feelings, and it did give people a chance to track me down and a lot of people said, "The same thing happened to me." Or, "I didn't feel the exact same way or had the exact same relationship with my parents, but I also wasn't overcome with grief."

Especially with the case with my mother... anyone suffering from addiction like that, the process is so painful, and you just feel so helpless, and I was constantly overcome with anxiety and worried that it was going to be even more terrible. I can't speak with authority about what it's like to lose someone from a terminal illness—which I'm sure is incredibly heartbreaking, and also has the same amount of helplessness—but I can imagine, eventually, when someone isn't getting better, and you kind of give up that kind of hope or optimism. I think [relief] is a kind of understandable response because it's not only the end of your suffering but the end of someone else's suffering.

Saying that out loud or putting that on paper still felt scary, but it was really important to me to be honest about my experience, because, without that, the rest of the book really would not be so significant. It was a huge change for me to go from being relieved that these people had exited my life to me suddenly becoming interested in them, because I find these artifacts from their life, and then going on this kind of an epic journey, traveling around to meet people, spending time where they lived, getting more details of their personalities and their lives, but also more context, both physically and geographically, and eventually be able to find compassion for them.

That radical change is really profoundly affecting in that it really offers a chance for anyone reading to understand that redemptive feelings toward loved ones, or getting to a place of grace or understanding, is really complicated. I found it particularly affecting when dealing with your relationship with your mother. I think we're so used to hearing about how selfless the loved ones of addicts are supposed to be, no matter how difficult the addict's behavior, and you were able to really beautifully deviate from that script—including, while visiting your mother at the Betty Ford Clinic—and demonstrate just what an impossible task that can sometimes be.

I can't stand scripts, and I had all this anger that flowed out... and it felt really important to talk about that in the book, and I did struggle until the end, to understand my mom's disease and have compassion for it, and I just can't imagine that I'm the only one who found it so heartbreaking to watch someone succumb to that disease. If you haven't spent a lot of time with an addict, the problem with addicts is that it's just a roller coaster with them. There's the narcissism, there's the abuse and the terrible self-esteem; sometimes they don't feel guilty at all, and they refuse to acknowledge what they've put you through. And that's what really came out of Betty Ford. I really had never confronted my anger before and, while it maybe wasn't the right time for it to come out, it was great that it did—not that it made any difference for my mother, but I think it was important for me to be able to say, "Hey, this sucked, and has been affecting my life. This is not just something that you're doing alone." Even if she never intended to hurt my sister and me, I'm sure it broke her heart to see that, but it was really important for me to be able to say, "This has been my experience, and if I'm not honest about that with you, then no healing will happen."

When addicts do successfully kind of beat their disease—which is so wonderful to me, especially because my mother was incapable of doing it for whatever reason—I just admire those people, because I understand what a daily painful struggle it is for them to stay sober and deny themselves their drug or vice of choice. But, also, if someone gets better, you're left with the experience of like, I'm glad you're better, but this was a shitty decade. And I think it's important for people who have been affected by addiction to be able to talk about that, both with the person who has caused them that pain and then with other people, to just say that this is hard, and this has affected me and my relationships, and it's an important experience to go through.

One thing being close to an addict will do is make you very aware of behavioral patterns, and I think it's clear from your book that it was really important to you to take an active role in your life, and not repeat any destructive patterns. Your independence really stands out, but even though it seems reactive at first, in contradiction to your parents, as you acknowledge in the book, you also realized so much of that nature was replicative of them, and their own love of adventure. Did realizing these similarities make you feel closer to them?

Absolutely, and going back to this thing I keep harping on about being honest—even though it was hard and embarrassing to be really honest about negative things, the negative narrative of my parents was one I was really attached to so, in a lot of ways, that was a lot easier to write about than the positive things. Like, the positive realizations were really at odds with what I had been telling myself about my parents, and this fantasy that I had emerged from them totally independent, and I just so happen to share these qualities of theirs, but I didn't wanna give them any credit for it. It was really difficult, realizing and admitting the positive things, but it, ultimately, felt really wonderful and absolutely made me feel closer to them. I mean, I definitely inherited their love of travel and desire to see the world, and how I managed to get away with telling myself that somehow I had nothing to do with them is absurd.

One of the most difficult realizations, that was ultimately incredibly comforting, was learning that I actually had a lot in common with my father, and that was a realization that I would not have been open to even a few years before because I only had negative thoughts about him. All of these wonderful qualities of his I eventually discovered, I could only see them in a negative light, saying like, "Oh, this is a person who was willing to pursue their dreams to the end, even at the expense of other things in their life." For a long time, I saw that as purely selfish as opposed to recognizing like, Oh, it's a complicated quality and being that kind of person can mean that you hurt other people. When I was working on this book, I realized that I am a person who prioritizes their dreams above their relationships and values their freedom and the ability to make crazy decisions or decisions that other people don't understand. Watching their lives—I didn't realize it at the time—really gave me permission to live the kind of life I wanted, and that gave me a lot of mobility, a lot of freedom, and I still actively make those choices now.

Did you ever worry that you might get trapped in trying to go deeper and deeper and find out more about your parents' lives and it would be bottomless?

I did worry about that... I realized at the end of it that, like, Well, I just wanna know everything. And I did find out so much and so many things that I had no idea were just parts of my parents' lives, but I didn't anticipate how painful that would be or how draining it would be to sit through these hours and days and months of conversations—especially when they were on topics that were upsetting. Or even if they weren't upsetting, hearing these wonderful stories about my parents' adventures, you know, those were wonderful conversations, but when the conversation ended, I would be left with, Well, I still know how that story ended, so how happy can I really even be about this? It almost makes the end of their lives worse, or makes me even more sad about what happened to them. So the research was just like this constant, unearthing excavation of painful material. But, of course, the deadline approached, and I was like, "Alright, you really have to switch your research to writing," and what I then realized was that that actually opened a whole new investigation, and that was when the investigation of myself started happening; the investigation of my parents ended, but the self-investigation and really looking at my life is what started when I sat down to write the book and I thought, Where do I fit into this? How does my childhood fit in? What are the memories that are gonna help me tell this story? And that allowed me to shift the foundation to this larger narrative.

My Dead Parents is available for purchase here.