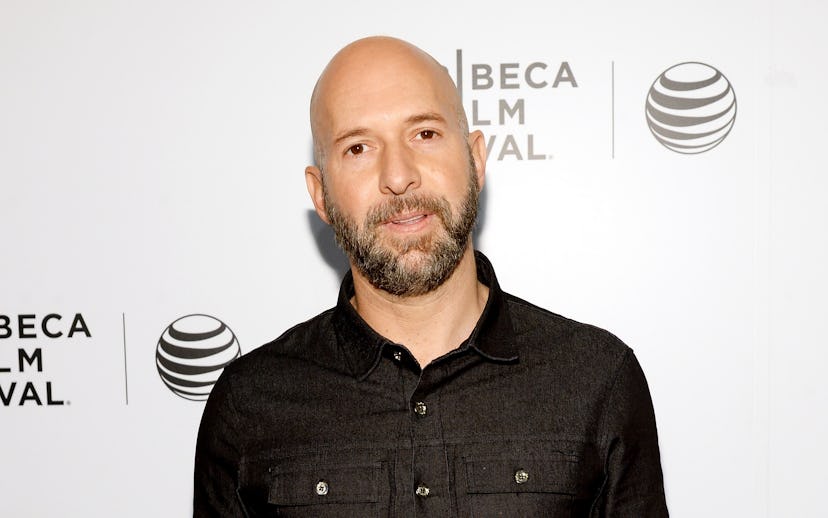

Neil Strauss On Writing, Sex Addiction, And His New Book ‘The Truth’

Ten years ago, a nefarious manifesto called The Game hit bookshelves across North America and quickly skyrocketed to the top of The New York Times Bestseller list, remaining there for a month-long residency while influencing the social behaviors of an entire generation of men and women. In the book, Neil Strauss, the gonzo-style journalist behind the biographies of Motley Crue, Marilyn Manson, and Jenna Jameson, blew the lid off the shady dealings of an underground society of pickup artists. By studying one character in particular, the Canadian-born Erik Von Markovik going under the moniker ‘Mystery,’ Strauss introduced the world to a dark subculture obsessed with power and manipulation, while also expanding the burgeoning Internet-based industry tenfold.

The subsequent attention that The Game garnered turned Strauss into a cult-icon virtually overnight. However, following a failed relationship with Lisa Leveridge, the guitarist in Courtney Love’s all-female band The Chelsea, and a bizarre stint as a doomsday prepper that culminated in a St. Kitts citizenship, Strauss suffered an identity crisis after realizing he was incapable of intimacy; years spent entrenched in the seductive community were indicative of a much larger emotional insecurity that threatened to wreck any sense of happiness. His newest book, The Truth, is a brutal analysis of relationships that features an ensemble cast of characters, including Rick Rubin and Seth MacFarlane, and follows the writer to marriage and fatherhood, complete with stories of orgies, ecstasy, and the love of his life, Ingrid De La O. Twenty stories above Manhattan at The Gansevoort Park, we sat down with Strauss over brunch to discuss writing, sex addiction, and the legacy of The Game.

Throughout all your books, especially The Truth, you’re very specific at recounting what’s going through your head at the time, while writing out exact dialogue from other people. What’s your writing process like?

I think one is that I take really rigorous notes. Anything that’s going in my life that I think is interesting, whether it’s going to be a book or not, I just take very intensive notes before going to sleep, no matter how tired I am. There are times when I may have been experiencing an orgy, things like drugs are involved, and at night, before I go to sleep, I somehow write it out. There are times where I’ll look at my keyboard and I can see my hands falling asleep; there’s this long string of random letters, but I’ll make sure I’ll get it out to capture the immediacy of the emotions. Other things I’ll do, if there are great lines, I’ll write them down. And sometimes, once I know I’m writing a book, because it never begins when I’m writing a book, say, when I was living in the house with all these women, I start recording certain meetings.

Dare I ask about the diary entries?

The diary entries were real diary entries, except for the one from Ingrid’s mind, where I asked her to tell me everything she was thinking at the time. I thought it was interesting to be so inside my head and my world, to take a step back from that and get that outside perspective. Kind of like [Faulkner’s] As I Lay Dying.

What was it like having Rick Rubin as a mentor?

We’d been friends for a long time. He was just a friend, but then he noticed that when I got everything I wanted with The Game, I still wasn’t happy. That’s when he started picking out the flaws in my logic.

You’ve traveled the world writing books with the likes of Motley Crue, Jenna Jameson, and Marilyn Manson. At the same time, you’re spending time with a lot of very neurotic and very confused men, whether it’s in rehab or at one of your book signings. What’s the juxtaposition between those two worlds like?

I don’t see them as distinct camps. They’re just different people and I gravitate towards whoever’s interesting. For example, Mystery in The Game is maybe more of a rockstar than Avril Lavigne; he’s fascinatingly over-the-top. I think the Maroon 5 guys dressed up as the guys in The Game for Halloween. I see who’s interesting and who has a story to tell or is boring in a unique way. For instance, Adam in this book is a guy who’s trapped in a dead-end marriage and can’t get out. I felt like that was a really relatable story.

After you wrote The Game, you had essentially expanded this community tenfold and developed a huge cult following. How did this affect your ego?

I don’t think I have much of an ego thing where any attention is going to change who I am. But I was also getting attention before the book came out; the character of Style in the community garnered a lot of attention in that world, not knowing a lot on who I was in real life. It’s more bizarre than anything [Laughs]. Maybe part of it is, “I wrote a book and people connected with it and were changed by it.” But to me, it’s not about me: it’s more about the book. If the books get all the attention and I get no attention, that’s ideal.

The Game was this character study of this community and was really about Mystery’s story, whereas The Truth is this very brutal analysis of yourself and your faults. It’s about unwinding years of ingrained psychological thinking. How difficult is it to write something like that, knowing all of these people are going to read it?

Two good notes there. One, I think you’re absolutely right interpreting it that way. In the other books, there were always other flawed characters because I’d be observing Mystery or whoever. In this book, I became the flawed character. I really thought that before this journey I was normal and everyone else was weird and I didn’t need therapy; I was just the neutral observer. Then I noticed how—I don’t want to say fucked up—but how I was just another flawed character like them. The second, I always write [my books] like nobody's going to read them. The other thing that helped was doing the books with Motley Crue and Marilyn Manson and Jenna Jameson. The problem was that they had to tell everything, no matter what anyone else thought. If I interview a celebrity who wants to do a book with me, and they say, “I’m worried about what my kids, wife, or fans will think,” then I won’t do the book. And I hold myself to the same standards.

How has your family reacted to it?

I don’t know. I can’t even guess, because I just don’t know.

How did all of this affect the way you approach the world?

I think it affected the way I see everything. If you think of how our behaviors have a software, understanding how it’s programmed in the first seventeen years, really helps you understand people on a whole other level. Really with a lot more empathy. When you see someone really wound up and angry, you really feel sorry for them.

What is love to you?

Love to me is acceptance; acceptance of yourself and others. Love is acceptance.

You also became a father eight months ago. What are some lessons you’ve learned having a child?

Mainly I’ve learned lessons to become a father because I really learned about what a parent does that creates trauma and creates certain behaviors. For example, one thing that I did before my son was born, I wrote him a letter telling him how his mom and I love each other and how he was wanted and born out of love. We’re saving it for him, and I feel like when he’s older he’ll appreciate it, to know he was born out of love. I guess if I were to say it in a soundbite, it’d be to raise my child with enough self-esteem that he doesn’t need The Game [Laughs]. That’s my goal.

How has developing more empathy and stripping yourself of all these layers you built up as natural defense mechanisms affected your skills as a writer and journalist?

I feel like I can have deeper conversations. I can show up and be more present. Kind of like Rick said, “You never wrote books about the light and the positive. Who knows what that will open up?” I think too often, I think the things we cling to are the things we should be letting go of. And I think you can let go of the bad stuff while letting in the good stuff.

What do you want as your legacy?

I think it’s something you can’t control because your legacy involves what other people think of you. Probably my most important legacy is with Ingrid and my son. That’s the most important legacy. It’s also realistic in the scheme of things: shit’s not going to last in the scheme of things. Nothing that we create is going to last that long.