Maybe you're feeling sad that summer has come to an end. Hey, I get it. It's difficult to say goodbye. But also, feeling sad is a good excuse to stay inside and read one (or all) of the following five books. Are they going to cheer you up and make you smile again? Possibly not? They're not exactly laugh-fests, any of them. But they are all among the best books I've read this year, and so you should read them too.

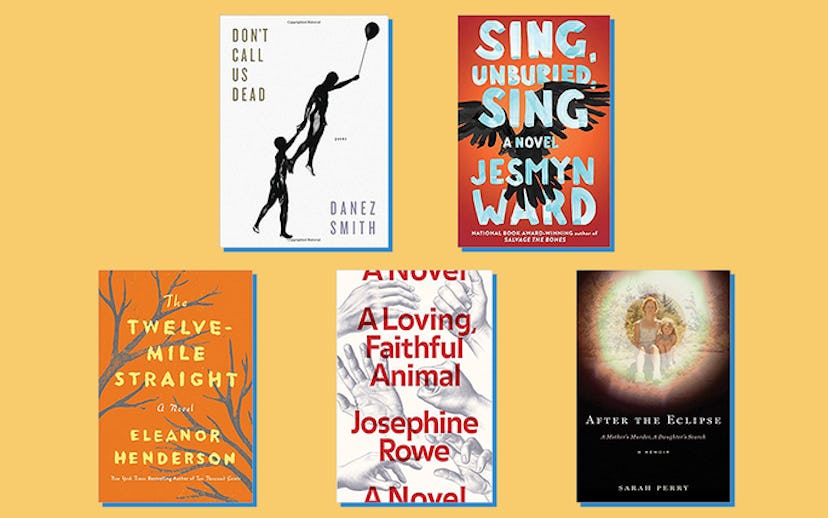

Don't Call Us Dead by Danez Smith (available September 5)

"Some of us are killed/ in pieces/ some of us all at once." Every line in Danez Smith's powerful new poetry collection settles into your skin this way, sticking and rooting itself, so that it's soon a part of you. Smith's work is astonishing, its power is a seething one; he demands attention. And Smith grapples here with attention-worthy topics, addressing everything from the plague of police brutality on the black community to what it is to contemplate love and death after an HIV diagnosis, making this slim book an essential part of every American's reading experience.

Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward (available September 5)

Only the fiercest of fables would take root in a place called Bois Sauvage, and that’s exactly what Jesmyn Ward’s latest novel, Sing, Unburied, Sing is: a wild, piercing mythic narrative, in possession of teeth sharp as the pointy end of an arrow, which exposes the difficult truth that there is no relief from time—or from history.

Spanning both the course of a couple of days and several generations of a Mississippi Delta-based family, Sing, Unburied, Sing, centers around 13-year-old Jojo as he and his toddler sister, Kayla, leave behind their beloved grandparents, Mam and Pop, and accompany their drug-addicted mother, Leonie, to pick up their father, Michael, at Parchman, the northern Mississippi prison where he’s been incarcerated for the past three years. Taking place from multiple perspectives—Jojo’s, Leonie’s, and, notably, that of Richie, a ghostly figure who, decades prior, was a 12-year-old inmate at Parchman along with Pop—the story is reminiscent of other epic Southern journey novels, notably William Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying. (Though instead of there being lines evocative of modernism’s purity, like “my mother is a fish,” Ward writes with an astonishingly lyrical quality; sentences vibrate with their own beauty: “her voice was a fishing line thrown so weakly the wind catches it.”)

Unlike in that archetypal road trip narrative, The Odyssey, here the monsters are sickly sweet-smelling white men and women, whose inescapable allure lays not merely in the pleasures they offer, but in their own imperviousness—to punishment, yes, but also seemingly to time itself. Their power resides beyond the realm of consequence; it exists outside of recent positive developments meant to combat things like institutional racism. Their power laughs in the face of things like social progress. As one characters notes about the injustices of the world, “Sometimes I think it done changed. And then I sleep and wake up, and it ain’t changed none.”

And yet, this story is not one devoid of hope, because it is one that is filled with love, particularly as seen in the relationship between Pop and Jojo, one that gets under the skin so that it’s impossible not to feel its fingerprints days after setting the book down. It’s a testament to the ways in which we learn to heal each other, no matter how imperfect the world or how much tragedy strikes our lives. It’s emblematic of how we must work to live within something bigger than ourselves, to be our best no matter how wild are the woods around us, no matter how easy it is to get lost. It’s a love that shows how interdependent we all are on one another, and how that isn’t a bad thing; or, in the words of Mam, it’s a way of knowing we’re none of us alone, “because we don’t walk no straight lines. It’s all happening at once. All of it. We all here at once.”

The Twelve-Mile Straight by Eleanor Henderson (available September 12)

It is 1930 in the Deep South, and a young, poor, unmarried white woman has just given birth to twins—one white, one black. The arrival of these babies sets off a series of catastrophic—and deadly—events. An innocent black man is lynched; a feckless scion skips town; and more and more details emerge about the real backstory behind the existence of these "Gemini twins." Epic in scale and intent, The Twelve-Mile Straight grapples with issues of race, class, and gender, and details the way power perverts our relationships with one another, often leading those with only a little of it to wield it harshly against those who have even less, and often to catastrophic effects. Henderson has crafted an intricate, rich narrative that beautifully stands up to the daunting task of portraying our country's horrifying history of racial violence and sexual oppression. While not always easy to read, The Twelve-Mile Straight feels necessary, and its story will resonate long after you've turned its final page.

A Loving, Faithful Animal by Josephine Rowe (available September 12)

Set in rural Australia in 1990, Rowe's stunning, gorgeously written novel, details the collapse of a family whose father, Jack, is irrevocably haunted by his time in the Vietnam War, decades earlier. For some people though, the ghosts of their past are more real than the people in their present, and they are helpless to do anything but destroy what is right in front of them. When Jack eventually leaves his abused wife, Ev, and two daughters, Lani and Ru, their lives continue, but are also undeniably haunted. The book's chapters each take place from the point of view of a different character, with Ru's narration opening and closing the book in the second-person, making you, as the reader, feel intimately involved with the tragedy of this family. And while the presence of pain never leaves this story, the beauty and compassion with which it's told, the deep understanding of the fierce love and shared toxicity that bind families together, makes the pain bearable, makes it feel important to bear witness to this tragic, gorgeously wrought story.

After the Eclipse by Sarah Perry (available September 27)

In 1994, 30-year-old Crystal Perry was assaulted and murdered in the home she shared in a rural Maine town with her then 12-year-old daughter, Sarah; it would be another 12 years before Crystal’s murderer was arrested. After the Eclipse is a powerful accounting of those years, a time in which Sarah was shuffled from house to house, never exactly finding a home; was, unbeknownst to her, considered a possible suspect in her mother’s death; and worked to rebuild her own life, following its utter devastation. The latter might seem an impossible task considering what Sarah had experienced, but what becomes clear while reading is that the foundation Crystal built for her daughter was one of inestimable strength, and would stand Sarah in good stead.

“I always try to say the book is about my mother who was murdered, not about the murder of my mother,” Sarah Perry explained to me recently over the phone. And that's exactly what the profoundly moving After the Eclipse feels like. Because while the memoir also ably explores the systemic misogyny and classism in small town America, as well as the effects that trauma has on an adolescent girl, it truly revolves around the life of Crystal, who shines from the borders of this often unbearably dark story as bright as the sun on a summer day.