Why ‘Pretty Woman’ Is Still The Perfect Romantic Comedy For Today

It’s all about the money

When news of Garry Marshall’s death broke earlier this week, fond remembrances of the prolific director flooded social media. Over the course of his multi-decade career, Marshall had worked with just about everyone—sometimes, as in his weirdly holiday-themed movies like Valentine’s Day, New Year’s Eve, and Mother’s Day, he worked with them all at the same time.

But Marshall is remembered best by most people—particularly women, regardless of age—for one reason, and one reason only: Pretty Woman. Is there any other movie that can be said to be practically every woman’s favorite (at least at some point in their lives)? The mere mention of the film compels most to recount how integral it was to their lives—sometimes literally; my coworker Jenna told me, “My mom went into labor with me while watching Pretty Woman.” As a romantic comedy, it was a pioneer in its genre, and just about every rom-com that’s followed in the last 25 years has paid tribute to it in one way or another, even if only through promising that its leading female actress was destined to become the “next Julia Roberts.” (Of course, that has stopped being a thing. But it was big while it lasted.)

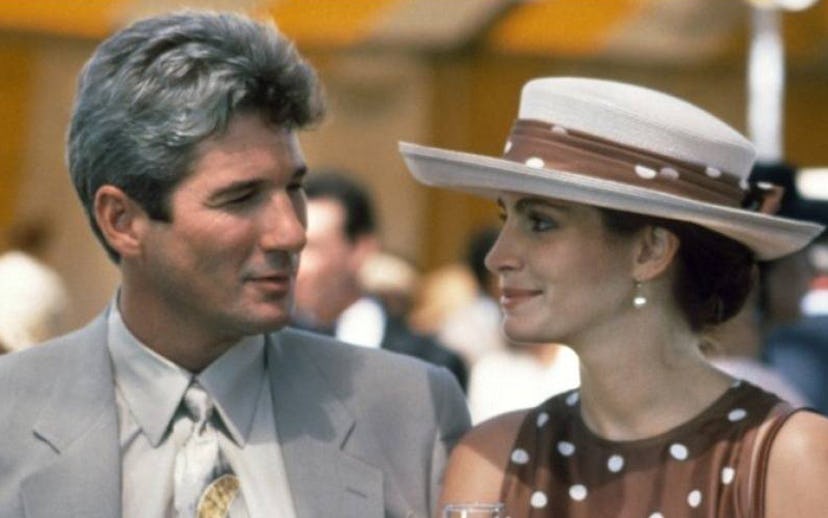

And yet, despite boasting an already storied director, a proven leading man, and an undeniably on-the-rise ingenue, the film’s runaway success seems a little strange at first glance, as does its designation as a romantic comedy. While the comedy part makes sense—Marshall revels in a comedic styling just one shade away from slapstick and the cast included a pre-Seinfeld Jason Alexander, who is super weaselly and terrible but still darkly funny, of course—the romantic aspect of the film feels a little bit off. On the surface, the plot might seem to be a classic, diamond-in-the-rough love story: guy meets girl, they get together even though they’re from totally different worlds, lessons are learned on both ends, conflict ensues, they end up together as the strains of opera play in the background. What that superficial synopsis conveniently leaves out, of course, is that the guy in the story is a wealthy man looking to pay for sex, and the woman is a working woman looking to provide it. In essence, this most beloved of all modern-day rom-coms isn’t really about the comedy (even though it’s funny), and it isn’t really about the romance (even if there’s a barefoot-in-the-grass-reading-Shakespeare scene), and it isn’t even really about the sex (even if there is an emphasis on the use of condoms, which is great). No, what this movie is really about, and what makes it the best rom-com of all time—or the most honest, anyway—is that it’s all about money. Or, as New York Times film critic Janet Maslin said in her 1990 review of the film: “Everything in the movie has a price tag.”

Women are conditioned from a young age to think of love and relationships and emotionally fulfilling sex as being separate from money, free from transactional constraints. And yet, there has been no point in our civilization’s history during which even ostensibly romantic unions were not, at least in part, about an exchange of something, whether it be goods, services, or just cold hard cash. And yet, the transactional reality of these exchanges is supposed to be kept quiet, and the women who participate in sex work have been historically marginalized (or worse), so that the dominant narrative of what love and relationships and sex are supposed to look like could continue to be the rather vanilla concept of man and woman fall in love and live happily ever after with no worries again for the rest of their lives because their lives before they met were already just fine, thank you. Pretty Woman refuses to participate in that narrative, though. Instead, it demands (albeit gently, albeit with a big, toothy smile) that we don’t forget that even though we might be watching a love story, what we are also watching is a financial transaction; the infectious laughter of Julia Roberts might be what stays with us the most clearly, but we can also hear the whispery sound of dollar bills being counted in the background.

This is why Pretty Woman is so subversive. It refuses to conform to a simple fairy tale plot; or, rather, it conforms, but it doesn’t leave out any of the details usually left for people to read between the lines. And not only does it not leave those things out, but it also makes them the showpieces of the entire story. After all, the parts of Pretty Woman that everyone remembers best all revolve around transactions and conspicuous consumption. There’s the scene in which Julia Roberts’s Vivian shows up the snobby shopgirls who initially refused her service; there’s the subsequent, iconic shopping montage set to the song “Pretty Woman” that has been replicated and bastardized in dozens of movies and TV shows; there’s the scene in which Richard Gere’s Edward snaps the lid of a jewelry box onto Vivian’s fingers as she tentatively reaches for the diamonds snaking within its velvety confines; there’s Vivian singing along to Prince in a bubble bath, right before negotiating just how much money she wants to spend the whole week with Edward. These are the scenes that stay with us even when we can’t remember much about when Vivian and Edward even get around to having sex. (I think a piano is involved at one point? Who’s to say, really.)

There are always going to be detractors, of course, people who are uncomfortable with the frank way that money and sex and love and relationships collide in this film and in life, but there are also always going to be people who promote abstinence as a method of birth control. And also, here are other quasi-uncomfortable parts of the film, such as the implication that the teleological goal of sex work is not money, but love, but nothing's completely perfect, right? It's still hard to deny, upon rewatch after rewatch, that this film rather singularly handles the most basic aspects of human unions—the desire to be recognized and taken care of, in a multitude of ways that transcend the ephemeral and get down into the hard truths of what it takes sometimes to just survive—and transforms them into something entrancing enough to engage generations of viewers, all of whom probably want just a little more sex and money in their lives.