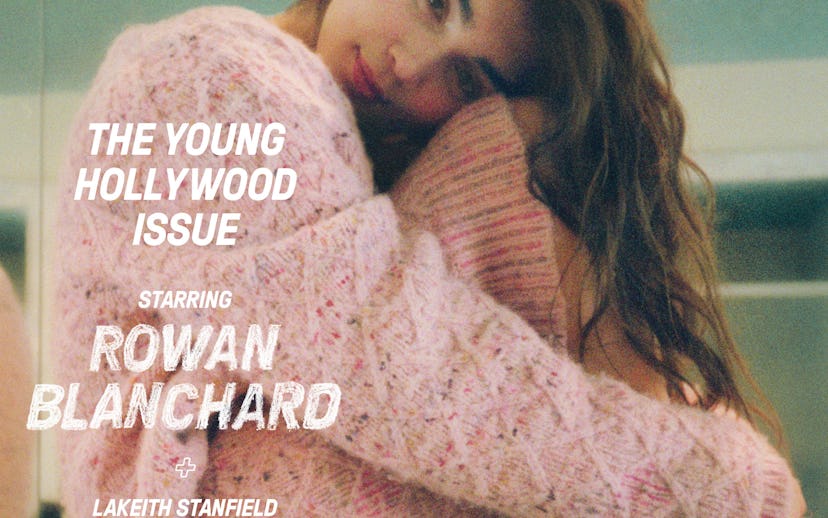

Rowan Blanchard Is Our May 2017 Cover Star

The 15-year-old actress is wise beyond her years, and has a crop of friends in Hollywood singing her praises

The following feature appears in the May 2017 issue of NYLON.

“We have been forced to know how to fight since day one,” Rowan Blanchard told a crowd of 750,000 demonstrators who gathered in downtown Los Angeles for the Women’s March this past January. “This is our advantage.” The Girl Meets World star, like hundreds of thousands of protesters in cities worldwide, was there to express opposition to newly sworn-in President Trump. While Blanchard will be the first to admit that she is hardly at the top of the list of people whose safety and civil liberties could be jeopardized by this administration, her words were a rallying cry to peers who felt powerless watching their political lives unfold on such a toxic note—especially after an election in which they had no technical say.

That’s because Blanchard is only 15. It’s almost hard to believe, considering her rousing speech, more pithy and inclusive than those of some celebrity speakers twice her age. Today, two months later, dressed in a stonewashed pink tee, jeans, and Mary Janes, she looks like any other teenager at this Los Feliz eatery, spoiling her dinner with a chocolate milkshake. But then you listen.

“It’s not that things all of a sudden changed on January 20,” she says, stirring her shake with a straw. “If Hillary Clinton had won, things would have obviously been much better, but now that we have somebody who’s the pinnacle of racism, sexism, xenophobia—all of this—we’re able to have conversations about where that started, and it was a long, long time ago.”

Blanchard has been an outspoken activist for years. When she was 13, she used her Tumblr account to pen a short essay on intersectional feminism, explaining to her followers that white women often approach political movements with a blind eye toward their own privilege as well as to racial and economic disparities. She regularly retweets Rachel Maddow and author/trans advocate Janet Mock. At least half of her Instagram posts address urgent issues, like the Flint, Michigan water crisis and the need for access to safe, legal abortions.

Her presence has proved magnetic, which isn’t something you can say about many online personas. “I was clutching my pearls a little bit because on the surface, a white cisgender young actress talking about Black Lives Matter and trans folks?” says Mock, who discovered Blanchard, along with some of her socially conscious friends (The Hunger Games’ Amandla Stenberg, black-ish’s Yara Shahidi) via Twitter. “I was like whoa. It was beyond the perfectly crafted tweet. It was conversations she was having with her fans. Young people in her generation have found a way to make art and to make noise.”

Ava DuVernay, director of Oscar-nominated films Selma and the documentary 13th, came to Blanchard the same way. “I follow voices on social media that appeal to me and that have a fresh take on what is happening in the world, especially around women and girls,” she says. “Rowan was someone who is really representative of the generation coming up right now.” DuVernay, who is currently making history as the first black woman to direct a movie with a $100-million-plus budget, decided to cast Blanchard in her much-anticipated adaptation of Madeleine L’Engle’s 1963 classic A Wrinkle in Time, due out next year. “Her character is one that we created that symbolizes a really big idea in the book,” she says. “When this part came up it made me think of her, because I liked her spirit and her spunk.”

Still, Blanchard knows there’s a tendency among some adults to underestimate people her age—these post-millennials who have alternately been referred to as Generation Z, plurals, and the founders. (“I feel weird about the founders,” she says. “That’s too much pressure.”) Distant relatives have told her that liberalism is something she’ll outgrow. “As if human rights are a phase,” she says, indignant. Once, on a red carpet, Blanchard and her Girl Meets World co-star Sabrina Carpenter were asked if they were “boy-crazy,” and when they said no, the reporter persisted with his assumptions: “But which one of you is more boy-crazy?” Most of all, she is constantly reminded that she is not what people expect of a former Disney Channel star.

Earlier this year, after three seasons, Girl Meets World was canceled amid dwindling ratings. “I feel good about it now in the sense that, as much as I loved my Girl Meets World family, working for the Disney Channel is stressful, and I have more freedom to do what I want and talk about what I want without feeling inhibited,” she says, sipping her shake. Perhaps surprisingly, she says there was never any blowback or criticism from Disney brass regarding her vocal politics: “I think they actually figured out somewhere along the line that no matter what they said I wasn’t really going to stop.”

Blanchard initially balked at doing the series, a reboot of the popular ’90s-era ABC sitcom Boy Meets World featuring protagonist Riley Matthews, the daughter of the original’s much-beloved couple, Cory (Ben Savage) and Topanga (Danielle Fishel). “Absolutely not,” she recalls thinking. “You know what happens to those girls.” Blanchard is often asked about her Disney predecessors, most gallingly during a radio program on which the question was posed whether she’d be “a Miley, a Demi, or a Selena” (as in Cyrus, Lovato, and Gomez). She hates this narrative—the game, not the players. “I knew the show would end someday, and I didn’t want there to be this weird part where it was like, good girl, good girl, good girl, and then, all of a sudden, bam, she’s going to show her boobs,” says Blanchard, laughing. She occasionally punctuates her serious thoughts with a reflexive giggle, and sibilant words reveal the faintest lisp.

Blanchard read the script, felt it was different, and clicked with the creator, Michael Jacobs. Like any Disney show, Girl Meets World was hammy, lesson-oriented, and scrubbed of nuance, but for a target audience aged six to 14, it tackled smart topics like cultural appropriation and autism. She grew close with her TV mom, and together they tried to influence the direction the new series would take—specifically avoiding focusing on romance, the way the original series had.

“I had expressed very adamantly that I wanted the character to be smart, self-sufficient, and to have interests 100 percent outside of relationships,” says Fishel, who was one of two women to direct episodes. “I didn’t necessarily get my way in that regard.” There were eventually some dating plotlines, though Fishel concedes the primary relationship in the show was between Riley and her best friend, Maya.

Blanchard was tight with her castmates, though her taste for old movies, abstract painters like Agnes Martin, and her fierce engagement with politics surely set her apart. Fishel remembers a day when she took her young female co-stars to the Huntington Library near Pasadena and asked them a bunch of thought-provoking questions she’d prepared ahead of time. One of them related to personal happiness, and Blanchard took the opportunity to reflect on the rah-rah positivity of glib self-empowerment. “Her response was basically, ‘It’s important that we recognize that our happiness is not 100 percent self-determined, and it bothers me when people act like our circumstances are something we just need to think our way into,’” says Fishel. “I almost had to stop walking. I tend to be one of those people who think it’s within your power to change anything. How utterly incorrect and privileged.” She pauses. “Rowan really is pretty special.”

Blanchard is redefining what it looks like when a child actor outgrows his or her space. If you’ve been doing kid-friendly programming since you were five, like she has, it’s gotta be tempting to take a claw hammer to that pre-fab, wholesome image. Historically, sexuality and substances have assisted with this messaging. But right now, in this climate, being a smart, hyper-informed young woman is just about the most dangerous thing you can be. “Part of my rebellion is saying, ‘I’m going to educate myself,’” she says.

As if on cue, someone decides to remind Blanchard that there are still plenty of people out there who hate women and want to degrade them. After spending the week on a soundstage for ABC’s The Goldbergs, a four-episode arc in which she plays the editor of the school sci-fi magazine, Blanchard had wanted to get some fresh air, so we’re heading on foot to Skylight, the local bookstore. Blanchard is wrestling with the criticism that gets lobbed at feminist celebrities like Lena Dunham and Beyoncé, which is how to account for her participation in systems (fashion shows, magazine shoots) that reinforce hierarchies. She’s thinking out loud, stopping herself only to take a deep breath and start again, making peace with the fact that the cost of idealism is often scrutiny.

A potbellied man approaching Social Security age walks by in the opposite direction. He loudly whispers a lewd comment to Blanchard. What happens next will be painfully familiar to every single woman alive. Blanchard continues talking, perhaps thinking I didn’t hear, or that, in any case, we shouldn’t let him win by derailing the conversation. She stops. “See, that makes me feel sick right now,” she says. She turns around, her fists balled up, strangling a scream—the perfect insult—as the distance between us and him increases. “Like, what the fuck is that? Why does somebody feel the need to do that?” she says, and slowly resumes walking. “Please write about this.”

Experiences like this formed the basis of Blanchard’s political awakening, dating back to when she was 11 or 12. Every time she hung out with a close girlfriend, that friend would be verbally harassed, until eventually it starting happening to Blanchard, too. She never knew what to say. “I think one time I flipped somebody off, and that was a huge moment for me, but then it kind of sucked after because it was a bunch of frat guys just laughing at us,” she says.

Blanchard was raised in Los Angeles in a progressive household. Her parents are yoga teachers, and her dad, Mark, is also a director—in fact, it was when she accompanied him to a meeting with his agent that young Rowan, who’d already been staging amateur bedroom productions and dreaming of Broadway, got signed. Blanchard went to public school until sixth grade, then switched to on-set tutoring (she is currently enrolled in the prestigious Dwight School’s online program), but she credits being “a hermit” in her room on the internet with her formative education. “I really owe everything that I do to teenagers on Tumblr who were considerate enough to teach other people about things—not like the Susan B. Anthonys, but, like, Adrienne Rich and Angela Davis,” says Blanchard, who is a micro-generation behind trailblazer Tavi Gevinson and has written for Gevinson’s online magazine, Rookie.

At the bookstore, we pass a display table with a copy of Jessa Crispin’s book Why I Am Not a Feminist. In it, Crispin argues that the word has been co-opted by capitalism, watered down to the point of meaninglessness and sold on a T-shirt. “Yeah, I totally agree with that,” says Blanchard. “But at the same time, I don’t know if I would have identified as a feminist if I didn’t see neon prints that were like, feminism rocks.” It’s complicated, and Blanchard is okay with that. She likes gray areas. She identifies as queer, and this is also complicated. “I noticed people who were older saying, like, ‘She’s appropriating a term and it’s a slur,’” she says, picking up a copy of James Baldwin’s Collected Essays. “I had no idea, actually. I just don’t understand why you’re straight or gay. I don’t understand why you want me to be one of two things. What is the driving force behind binaries? I don’t want to think about harsh terms like Democrat or Republican. I want to be in a bizarre realm where people are proposing ideas that have never been put into place.”

It’s almost surprising that Blanchard’s career is in acting, not because the profession isn’t worthwhile and challenging, but because her mind is working overtime, and it would be curious to see what she would create on her own. Like Fishel says, she is not “a puppet,” and there aren’t a lot of great roles that successfully grapple with the adolescent experience—Blanchard can only name two recent examples (American Honey and 20th Century Women). “If you’re deliberately making a teen movie, then you’re obviously going to talk down to the teenagers because you think that’s a separate genre,” she says. “In December, I saw The Last Picture Show for the first time. Sure, you could label that a teen movie, but really it’s just an amazing film.”

As it turns out, she tells me, she asked to “shadow” DuVernay on the set of Wrinkle. “I get asked to be shadowed every day, but most people don’t follow through,” says DuVernay. “Not only did she follow up, she shadowed me on three different days, which was a lot. I was wildly, wildly impressed. Whatever she decides to do, she’s one that attacks it with a real passion.”

For Blanchard it was an eye-opening experience. In the first place, she felt lucky that DuVernay invited her to join the cast. “To be validated like that was very assuring,” she says, tucking her long dark hair behind her ears. “People hesitate to see me because I was on the Disney Channel and it’s fake acting or whatever.” Furthermore, she was blown away by the director. “Everything happens from the top,” Blanchard says when asked what she learned. “A lot of the male directors I’m working with yell for no reason to prove that they can get a cast in line. But Ava knew the name of every single person on that set. She talked to every single one of them, and that set ran because of the way she treated people.”

Blanchard remembers a particular moment at the start of production that stayed with her. “Ava said something along the lines of, ‘It’s so incredible to direct a project about a girl like me, starring a girl like me,’” she recalls. (Storm Reid, who plays protagonist Meg Murry, is black.) “Storm kind of started crying and they ended up hugging and I was just watching this happen like, ‘Oh my god, that’s really huge.’ Nobody knew what to say. This movie is special. It’s one of those things that gets an asterisk.”

We break so that we can pick out books for each other and meet back at the tree in the middle of Skylight. I give her Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life and Emil Ferris’s new graphic novel, My Favorite Thing Is Monsters, which is about a 10-year-old-girl in 1960s Chicago who tries to solve the murder of her upstairs neighbor, a Holocaust survivor. It’s styled like a teenager’s diary. She gives me Maggie Nelson’s Bluets, a slim collection of poetry and reflection. “This is my heart in a book,” she says. “You’re not going to spend too much time on it, but it’s going to save you forever.” She also picked out I Am Not Your Negro, which is a companion to the Oscar-nominated documentary about James Baldwin. “I saw the movie with a friend, and we were getting so irritated because we wanted to write everything down, and they finally released a full transcription of the film,” she says.

Exiting the store, talk turns to the thorny issue of celebrity activism, and whether it helps or hinders causes. Janet Mock believes that “an informed celebrity is definitely an asset to any movement. An uninformed celebrity who is kind of following the trend—that’s not helpful.” Taking it one step further, is it the obligation of people with a platform to speak up? Was Blanchard upset when a self-proclaimed feminist like Taylor Swift didn’t endorse a candidate in the last election?

Blanchard thinks. “There’s a part of me that was getting incredibly frustrated, like, ‘How is anyone not talking? How are you not commenting?’” she says. “Specifically with celebrities that have so much power, I’m like, Maybe you wanna do something with that. But I’m not super-duper concerned with Taylor Swift as much as I am getting young girls to identify with [politics] for themselves.”

This is her philosophy: She’s not here to tell other people what to do, but she does expect thoughtful engagement. It’s not easy. In February, Blanchard’s mother had to hustle her away from two male protesters at the United Talent Agency’s rally against Trump’s travel ban, which targeted Muslims, because she became too angered by their anti-immigration stance. “I guess this is the downfall of the internet—I can’t talk about something like that in that situation,” she says. “It’s so much easier for me to get behind a computer.” But she’s not trying to change the minds of guys like that, or the pervert who passed us an hour ago, anyway. “I’m concerned with the 12-year-old girl who gets in my comments section to say that being gay is a sin,” she says. “I am willing to have a conversation with somebody who doesn’t agree with me if it’s a conversation, if you can give me facts, not the fucking Bowling Green massacre [the fictional event cited by White House counselor Kellyanne Conway].”

Blanchard has also been seeking the advice of actresses older than she, Fishel and Room star Brie Larson among them, specifically when the current political mood really gets to her. “These women are the ones who are protecting me,” she says, preparing to head to a friend’s house. They might see it differently—that Blanchard is doing just fine on her own. Fishel even looks up to her younger peer. “I just keep reminding Rowan that everything she has inside of her, she can put out to the world,” she says. “And that’s going to change the world.”