Life

Why Decriminalizing Sex Work Is A Life Or Death Issue

“If you don’t want prostitution, my god, give people jobs! Help them!”

Earlier this month, Lily Allen issued an unusual public statement via Instagram: Four years ago, during her ‘Sheezus’ tour, she slept with female escorts “cause,” she wrote, “I was lost and lonely and looking for something.” Allen concluded, “I’m not proud, but I’m not ashamed. I don’t do it anymore.”

According to Allen, the Daily Mail had obtained copies of her forthcoming memoir, My Thoughts Exactly, which includes a section on that experience, her deteriorating marriage, and her postpartum depression. In order to prevent the tabloid from making the situation “sound worse than it was,” Allen wrote, she’d rather have people hear it from her first.

As Jezebel’s Tracy Clark-Flory wrote last week, Allen’s announcement prompted “an avalanche of tabloid stories” about what happened on the singer’s 2014 tour. “I’m assuming that Allen paid consenting adult sex workers for their time,” Clark-Flory wrote. “That she has to ‘admit’ and ‘defend’ that, particularly within the salacious tabloid realm, is unfortunate.”

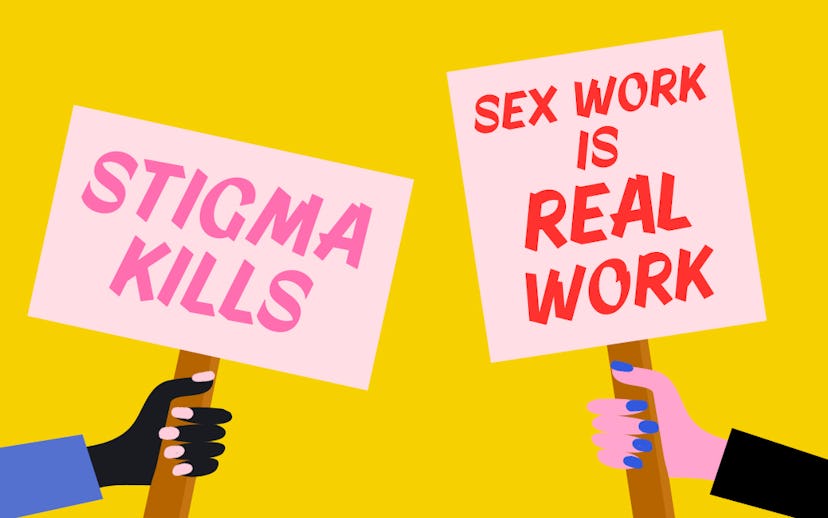

If the media frenzy surrounding Allen’s announcement revealed anything, it’s that sex workers—and their clients—are still deeply stigmatized. More often than not, though, that stigma has more harmful consequences than a few invasive tabloid stories.

In 2014, the year of Allen’s Sheezus tour, local and federal authorities conducted more than 40,500 prostitution-related arrests in the United States, according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s annual Crime in the United States report. The report, which relies on information from local law enforcement for much of its data, uses a loose definition of prostitution that elides the fact that prostitution-related arrests aren’t really prostitution arrests in the first place. Some cities allow police to arrest people for “loitering for the purpose of prostitution,” meaning that police can arrest people for looking like sex workers. Until recently, NYPD officers were allowed to seize condoms from suspected sex workers, which left street-based sex workers more vulnerable to sexually transmitted infections and HIV. NYPD officers are still allowed to seize condoms as evidence in cases involving sex trafficking.

Chicago’s city council unanimously passed its own loitering law in June, skirting civil rights groups’ warnings that it would disproportionately target women of color. New York’s own loitering law, which has been on the books since 1976, does just that. According to a 2016 report by the Village Voice, 85 percent of those charged under the loitering law between 2012 and 2015 were black or Latina women, some of whom were repeatedly targeted by police. Most arrests were made in a handful of neighborhoods, and trans women were particularly vulnerable, the report found.

For a time, the difficulties of street-based sex work—from arrests to assault, robbery, and rape—encouraged many sex workers to begin advertising online, both for their own safety and because it provided a better opportunity to screen clients, negotiate rates, and find community with other sex workers. But in March, the Senate overwhelmingly voted in favor of the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act, a bill that sex workers said would make their own work more dangerous and stigmatized while making it harder to find and help actual trafficking victims. The House passed its own version of the bill, the Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act, in February.

The effects were immediate. VerifyHim, a screening site for online daters where some sex workers vetted clients, took down its communication tools in April, according to Rewire.News. Craigslist took down its personal ads section the previous month. And just days before President Donald Trump signed SESTA-FOSTA into law, federal authorities shut down backpage.com, a controversial personal ads website that was the focus of the SESTA-FOSTA debates and which The Cut described as “the most accessible online marketplace for sex workers.”

Kate D’Adamo, a national policy advocate at the Sex Workers Project, told NYLON that SESTA’s effects were immediate and far-reaching—and that they were exactly what sex workers said would happen. In the wake of SESTA-FOSTA, sex workers have reported a rise in economic insecurity and even homelessness, a need to lower their safety and screening standards in order to make ends meet, an increase in street-based sex work, according to a fact sheet provided by Survivors Against SESTA.

D’Adamo said she spoke to sex worker outreach organizations in Seattle, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. who reported negative and abusive conditions. “There were a lot of reports of people who were contacted by predatory third parties who were basically saying, ‘Do you want to work for me? Because you need me to get clients,’” D’Adamo said.

Ceyenne Doroshow, the founder and executive director of Gays and Lesbians Living in a Transgender Society, put it more bluntly. “Because of the situation, you’ve now given pimps new employment,” Doroshow said. “You haven’t heard the word ‘pimp’ in a very long time. It’s come back.”

Both D’Adamo and Doroshow told NYLON that in addition to affecting sex workers’ livelihoods, the legislation has been detrimental to their mental health. “There was one person who I knew—I’m friend with a very close friend of hers, who said ‘I’m not going to do street-based work anymore, I can’t take it,’ and took her own life,” D’Adamo said. Doroshow mentioned another woman, a young transgender sex worker named Vanity, who died from suicide last week. “Under these laws, she lost a lot of income, she was very depressed,” Doroshow said. “The loss of this young lady has traumatized our community again. Where was the help for her? She couldn’t get help, because she couldn’t afford it.”

For sex workers, the ongoing fight against stigmatization and criminalization is life or death. If SESTA and FOSTA has had any positive effect whatsoever, though, is that it has encouraged a new wave of sex-worker led activism. And sex workers aren’t just fighting back against SESTA—they’re advocating for full decriminalization, which they say will make their work safer.

D’Adamo and others organized the first federal sex worker lobby day, where sex workers met with lawmakers on Capitol Hill, on June 1. “We brought people in to talk about what impact the bill had, and to talk about the importance of speaking to sex workers when those bills are passed,” D’Adamo said. The following day, sex workers across the country gathered for International Whores Day marches, where opposition to SESTA-FOSTA took center stage. Doroshow will be part of another, New York-specific lobbying day in Albany in October.

The surge in engagement is “based on a history of sex worker activism” and wouldn’t have been possible without a pre-existing network of sex worker organizations and advocacy groups, some of which have been around for decades, D’Adamo said. “I wouldn’t say this was the beginning of anything, but I think it was the catalyst to a new chapter in sex worker rights in this country.”

As a result, the sex workers’ rights movements is finding allies in the electoral realm. In New York City, state senate candidate Julia Salazar has expressed support for decriminalization, which The Appeal’s Melissa Gira Grant noted was “unusual for a person running for office,” even in an ostensibly progressive city like New York. Last month, a few dozen sex worker canvassed in Salazar’s district, where they spoke to prospective voters about Salazar’s support for abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ensuring affordable housing for all, and, yes, decriminalizing sex work. The event was co-sponsored by the Democratic Socialists of America, of which Salazar is a member.

Mandating that police officers give tickets out for prostitution-related offenses instead of arresting people would be an easy first step that would “actually go a long way in New York State toward decriminalization,” Salazar said in an interview with The Appeal.

In an interview with NYLON, Doroshow similarly said that having police officers give tickets for sex work-related offenses—”without a fine,” she clarified, since sex workers who are most vulnerable to policing, particularly trans women of color, live below the poverty line—would be a good start. Full decriminalization would also require the expungement of sex-work related offenses from people’s records, as well as increased funding for anti-poverty organizations and other harm-reduction groups.

“You have to put something [else] in place,” Doroshow said. “If you don’t want prostitution, my god, give people jobs! Help them!”

Both D’Adamo and Doroshow noted that sex workers’ rights aren’t a single-size issue, and other progressive movements should ally themselves with sex workers who are fighting for criminalization.

D’Adamo said that in addition to LGBTQ groups and public health organizations, groups like Black Lives Matter, Indivisible, and even the Women’s March have been instrumental allies to the sex work movement. “It’s such an intersectional issue,” D’Adamo said. “It touches on poverty, criminalization and policing, race, gender, migration. I don’t think that every organization needs to be a sex worker organization, but I think that recognizing economic survival—and the way that people are piecing together survival—is a cornerstone of every one of these issues.”

“We’re really trying to get the community to be all aligned,” Doroshow said. “Black, white, purple, cisgendered, she, him, they, all of it. We need to be in one room together.”