Entertainment

Slvt Cult Makes Shocking Feminist Art Designed To Grab Attention

Now is the time for the pussy to grab back

Pretty much everyone’s heard about that law designating any dwelling where three or more women live together in a brothel. It’s a powerful story, but a false one; yet, it has circulated since the 1960s, and it’s the basis for how Slvt Cult, a collective of female artists living and working together in the D.C. area, got its name. It began as a joke, then evolved into an informal moniker before the members embraced it as a way of pushing the boundaries of art and identification.

Maggie Famiglietti, one of the founders of Slvt Cult, met D.C.-based photographer Kate Warren through the collective, and there was an immediate synergy between them and their work. Both are outspoken, passionate about elevating female voices, and not afraid of ruffling feathers in the process. “There’s a lot of feminist artwork being done that I really appreciate,” Famiglietti says, followed by a forceful exhalation that hints at exasperation, “but I’m still seeing a lot of work that’s soft.” Unsurprisingly, then, Famiglietti's and Warren’s work lands like a punch to the gut.

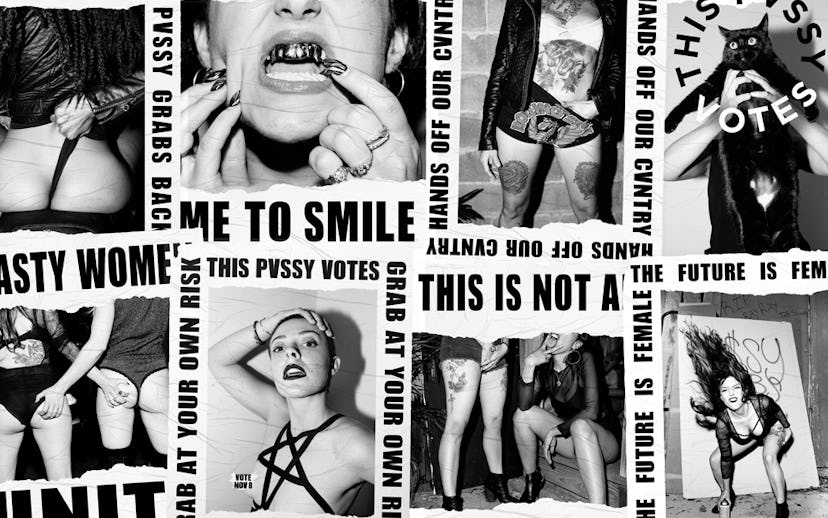

Their most recent and ongoing project, Pussy Grabs Back, subverts any soft norm by invading public spaces with images of women expressing themselves in ways that are considered aggressive, angry, and deeply taboo. In one image, a woman grabs her crotch through a tight leotard. In another, a woman sits in a doorway, legs spread and tongue jutting out between her fingers in a symbol of oral sex. The caption reads: “THIS IS NOT AN INVITATION.”

Pussy Grabs Back began as a response to the release of Donald Trump’s recorded lewd comments about women during the run-up to the November 2016 election. Warren and Famiglietti were angry, and, Warren says, through anger, inspired to “make work that created spaces for women to be angry and to feel safe talking about how triggered they were” by the Trump’s statements. They began by bringing women together for salon-style shoots where they were encouraged to wear the clothes that, “they wouldn’t normally wear in public for fear of soliciting unwanted male attention.”

And, as cisgender primarily hetero women, the artists focused on inviting women who occupied spaces outside of their own, in an effort to create a more representative project. The photos were shot late at night in back alleys, a setting women are warned against inhabiting, lest they are attacked. Warren says that the photos are “really aggressive and angry,” designed “to communicate, in part, the emotional experience of feeling like prey every time a woman leaves the house.”

Women opening up enough to show anger is, Famiglietti says, one of the things that make the images so powerful. She explains that restraint is a mechanism for “self-protection, and that’s definitely not fair.” Pussy Grabs Back takes the reality of women feeling unsafe and flips it on its head, by forcing the public to consume images of women in a dual state of empowerment and anger. The images have become popular on social media, but Warren and Famiglietti agree that the most impactful space their art has claimed is on the streets.

The images are downloadable, and people are encouraged to hang them in public spaces. Putting the posters up on public walls, Warren says, forces pedestrians to spend more time with the work than they would in a gallery or online, which is especially important if they find the work uncomfortable. “Usually, the street is a place where women have less power because men are catcalling them or following them home,” Famiglietti adds, “so to really strongly almost attack people with this imagery is the opposite of the typical experience for a woman.” Suddenly, the very people who may be making women uncomfortable through their language or behavior are being forced to see women as anything but weak.

The Pussy Grabs Back project is ongoing because the problem of women feeling unsafe not only existed before the election, but it also exists now and will continue to exist until men stop turning public spaces into a gauntlet women are forced to run. And while many women feel unsafe, clapping back at men who use harassment as a perverted pickup tool, Warren and Famiglietti have found that a side effect of their work is a willingness to lay down some truth. Both warn, “Lord help the man who catcalls me.” They’re more than ready, Warren says, to dish out “a little education” to those who dare to get in their way.