Entertainment

‘Star Wars’ Means Finally Saying Goodbye To My Father

a lifelong journey

The legend, in my family, goes like this: The day that the original Star Wars was released, my parents had friends in from New York who heard a hot tip that it was going to be the next big movie, and that they “had to see” it opening night. They procured tickets to see the premiere at the Esquire Theater in Chicago, and decided to smoke a ton of pot. (“Maui Wowee,” my father would tell me. “It was some truly primo shit that we had flown in straight from Hawaii.“) When they showed up to the theater, they were one of the last people to arrive, and had to sit, very high, in the very front row. (Hey, it was the seventies.)

"You know when that ship comes out from the bottom of the screen? And those words that shoot up out of nowhere?" my dad recalled. “We had never seen anything like that before. The theater actually shrieked. My mind was blown. It was actually like being in space.” My mother would go on to say that she has never had a more thrilling experience with music, film, or theater. “It had never been done. Here we were, stoned out of our minds, in the front row of history.”

I’ll never know if the Maui Wowee was really that good or if the theater did indeed yell and cheer. But I do know my parents were forever changed. My father found his own personal Citizen Kane. My mother used Star Wars as a lens to understand Jungian theory vis-a-vis Joseph Campbell’s seminal A Hero With A Thousand Faces. (It was reprinted to frame Luke Skywalker as the archetypal hero heeding “the call to adventure.“) They had the first three movies in stump-brown, plastic VHS cassettes with my father’s handwriting in red permanent marker. Star Wars. Empire Strikes Back. Return Of The Jedi.

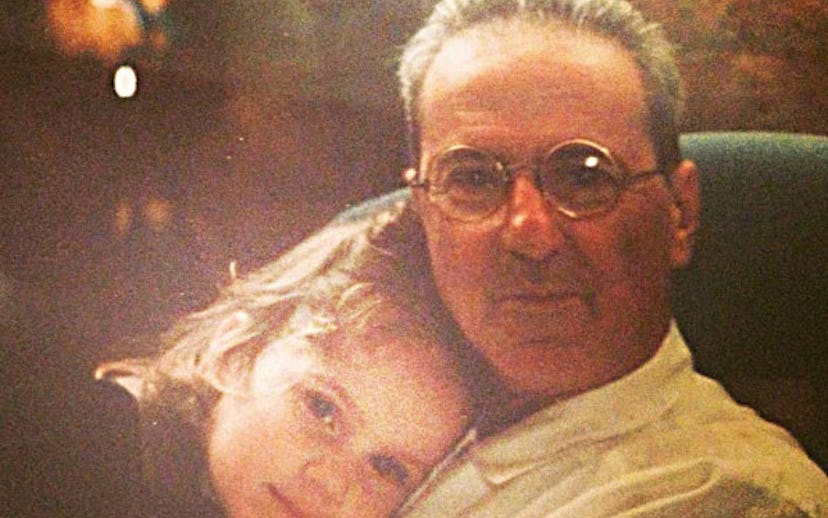

The first time I sat down to watch the film with my father, I was three, and I have a fuzzy albeit apparently real memory of being terrified by the cantina scene. (”He doesn’t like you. I don’t like you either!“) It felt scary. I made him turn it off.

Stubbornly, my dad tried again when I was five. This time, we had much better luck—and not just because I developed my first crush on Luke Skywalker and became bewitched by the assertive, graceful charm of Princess Leia. More than anything, I felt the same excitement my father felt as we watched. This was his favorite movie, and now I was experiencing it, too.

Suddenly, I became obsessed. (My mother explained to me that girls have a crush on Luke, and then they get older—and women have a crush on Han. Pretty nice summation of the appeal of the rogue, I’d say.)

Princess Leila, my parents would call me, and for years I believed my parents named me after the ruler of Alderaan. I would watch all three of the movies in one sitting, and after the “yub-nubs” wrapped up in Jedi, I would rewind, and restart. I wrote elementary fan fiction. My family rummaged through garage sales and scanned classifieds to feed my need for action figures. I had slave bikini Leia, Wedge, a Gamorrean guard, and even the stolen ship that Luke and the Rebels use to land on Endor. (Given the proximity to the release of Jedi, most of my toys were from the last entry, and my parents reluctantly watched their resale value shrink as I staged massive Kessel Runs.) There was nothing I loved more than this universe, where goodness prevails and even villains can be redeemed.

“I’m sorry, Claire,” my father would say matter-of-factly, using my middle name, “but the first Star Wars is the best. The other ones are just pale.”

“But, Dad, c’mon. Empire is clearly the most beautiful. It’s the most complex. ‘I love you.’ ‘I know.’ There’s a lot there!” I would argue as I got older.

He would shrug. “But the thing is, the first Star Wars is the story of heroes. The first Star Wars is the oldest story ever told.”

When my parents split up, I initially lived with my father, in which he negotiated his life as a single man with a daughter for the first time, ever. Our dinner conversations were strangely intellectual, us batting around thoughts and making grand statements about our favorite albums, the best songs, the actors my father taught me to love. He forgot I was a child. Instead, I was his dinner companion, his tiny sparring partner, and (he’d say this by clapping me hard on the back) his pal. He would ask me to rattle off his favorite movies, Curly Sue-style: ”Being There, The Double Life Of Veronique, Blade Runner,” I would say.

“What’s number one?”

“Star Wars!” we would say in unison. It was one of our favorite acts.

******

At the end of June, I turned 31, and my father returned to New York the place where he was born, the place I currently live, for the last time. He spent my birthday with me for the first time since I turned 21, traveling in on a whim. My life was a curiosity to him; I preferred Brooklyn when he had spent his whole life in Manhattan; my friends had sexualities and hair and skin markings that weren’t from his era; my career was based in the ephemeral. I didn’t make anything you could see or touch or hold.

But he admired it—he liked that I knew things, that I took photos with celebs, that I always came prepared with a quip or a take on a new album, film, or star. He loved stuff. I loved stuff. We would chat for hours about the fine cinematography of Dances With Wolves (he rightfully pointed out that the movie would have been greatly improved without Kevin Costner’s narration), the deliciousness of Dustin Hoffman, and the weird, decidedly political irony of the Rebel Alliance exploding the Death Star and dealing a blow to the Empire, only to appear at the end of the film as the exact militia they just helped overthrow.

How we got on the subject is a mystery, but one of my friends admitted that, one thing he never got was Star Wars. He claimed that it was the world’s most successful children’s movie, never veering out of the territory of PG. “It’s a movie,” he explained, “For children that adults somehow have co-opted.”

“Wait a second. You are confusing something pretty crucial,” I told him. “Just because something is universal, doesn’t mean it is just for children. Just because someone has whimsy doesn’t make it kids-only.” I flashed back to that 3-year-old, cowering at the bloody, severed arm in the cantina. I don’t like you, either. “You are confusing a film for everyone as a film for kids. Here...watch.”

I yelled across the room to my father (very literally, his hearing had become piss-poor.) “Dad, what is the greatest movie ever, ever made, in the history of cinema?”

“You mean, besides Being There, The Double Life Of Veronique, and Blade Runner?” he responded. “Well, there is only one.”

"Star Wars,” we said in unison. Decades later, we were still playing our game.

*****

The day the trailer for The Force Awakens was released, the first glimpse after the teaser, the one with Leia and the crushed Vader mask and Ray flying the Falcon—was the day that my father died.

His cancer was aggressive, and he fortunately passed without a great deal of pain, but it happened so quickly. My step-mother and I thought we would at least have the holidays with him—and I half-heartedly fantasized about taking him to see the newest installment.

I didn’t watch the trailer for weeks. I was afraid. I didn’t want to see it. I knew I couldn’t share it with someone who was no longer here. I wanted to tell J.J. Abrams to stop it, to stop moving forward, he was leaving my father behind.

That George Lucas’ magnum opus fascinated a father and his child is no real surprise. At its heart, Star Wars is a story about growing up, confronting the issues of your parents, finding redemption and forgiveness, and—symbolically—becoming your parent. Looking down at your metal arm, seeing your father unmasked and exposed and realizing their face was yours is certainly not an experience only limited to Luke. At the end, Luke receives the ultimate gift from a parent, one of validation: Hearing a father admit, “You already have [saved me]. You were right. You were right about me.”

I wish I could say that now. “I was right, Dad. I was right about you.” I could peel off that mask and understand the old man underneath, looking backwards on his life.

The last time we had a discussion about Star Wars was about two months ago, when I told him that I had a good, naively optimistic feeling about J.J. Abrams’ turn at the helm. “I don’t think I’m going to be able to see how it turns out,” my father said to me.

“Well then, I know how it ends,” I lied, “and I’ll tell you.”

“How?” my father asked, clearly believing the impossible.

“They all get back together, Dad. They all get back together, every one of them, Han, and Luke, and Leia, and Obi Wan, for the greatest battle this universe ever saw. And they win, because it’s the oldest story ever told. That’s how it ends.” No matter what happens this weekend, for me, this journey will be mine and it’ll live on, forever and ever, in a galaxy far, far away.