Entertainment

YES: Uma Thurman, Quentin Tarantino, And The Issue Of Consent In Art

What are we complicit in?

In 1966, Yoko Ono's "Ceiling Painting, Yes Painting" was shown at London's Indica Gallery. It's an interactive work: Gallery-goers could climb the six steps of a white ladder to reach a platform; once there, they would find a magnifying glass, hanging by a chain and attached to a framed sheet of glass, suspended from the ceiling. By picking up the magnifying glass, and using it to look at the frame, a single word could be found: YES.

It was through this show that Ono met John Lennon, her future husband and artistic collaborator. Theirs was a partnership that was mutually fruitful, both professionally and personally, but Ono's solo artistic endeavors, particularly pre-Lennon, are sometimes treated as an afterthought. Though unfortunate, this is unsurprising—not only because famous creative men frequently eclipse their creative partners, but also because, well, as Lennon himself famously said at the time, he was more popular than Jesus.

And yet it is Ono's work that's worth revisiting right now, with "Ceiling Painting, Yes Painting" in particular standing out because of what it says about the implicit exchange that takes place between an artist and a viewer, because of how—by looking at art, by listening to music, by watching a film—we, as an audience, consent to this exchange. In effect, an artist is offering something up to us through their work, and we receive it. We say, YES. It is through this consent, then, that we become complicit, in however small a way, in the artistic experience we are sharing. All the more reason, then, to fully explore what it is that we are agreeing to be a part of—and with whom.

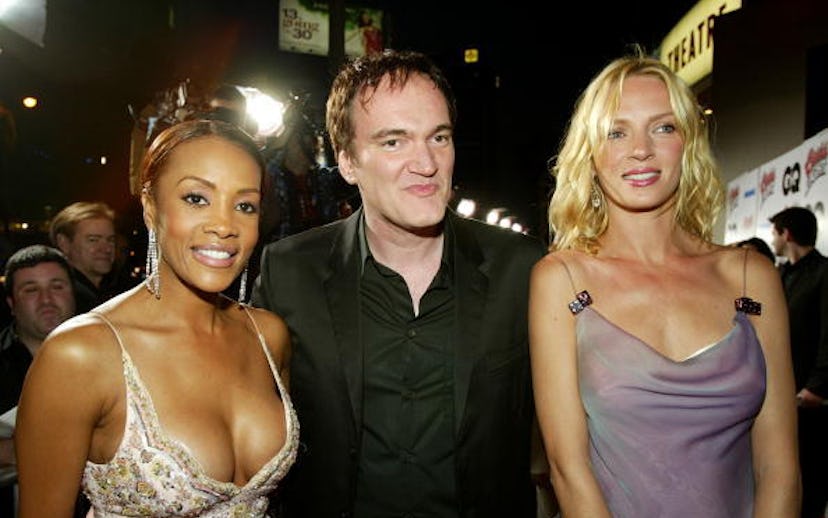

On Saturday, The New York Times published "This Is Why Uma Thurman Is Angry," in which writer Maureen Dowd spoke with Thurman about the actress's experiences working with producer Harvey Weinstein, who, Thurman says, sexually assaulted her during their working relationship. Thurman has been acting for three decades, but it was in 1994, with her iconic role as Mia Wallace in the Weinstein-produced, Quentin Tarantino-written and -directed Pulp Fiction, that she became a star, earning her first Academy Award nomination. Ten years later, Thurman would appear in two other Weinstein-produced and Tarantino-helmed films, Kill Bill Vol. 1 and 2, but not as a supporting character, rather as a star and collaborator of Tarantino, even earning a writing credit (though she's listed as "U").

Thurman tells Dowd that by the time she was on board to film the Kill Bill movies, she'd told Tarantino about being attacked by Weinstein and that he "confronted Harvey," which led, Thurman said, to a "half-assed apology" from Weinstein. Following this, Thurman would go on to make the films, which would vault her into an even more glorified position in the industry, including earning her second Academy Award nomination. And it's easy to see why. While Thurman was unforgettable as Mia Wallace, she was part of a large ensemble in Pulp Fiction, no single piece more important than the whole, no one actor more important than the man behind the camera.

The Kill Bill movies were different. Thurman is central to the films in a way that is rare for an actor in Tarantino's work (Jackie Brown's Pam Grier being the other notable exception). And while Tarantino did interviews citing Thurman as his muse, and comparing their relationship to that of Alfred Hitchcock and Ingrid Bergman, she seemed to transcend that frequently pigeonholing designation, not least because she was explicitly involved in the creation of the character she played, something that seemed to subvert the myth of the muse as mute inspiration. Thurman, it was clear, had a voice and power and a hand in this piece of art; she was a willing participant. And it was Thurman's role as a participant in this film that made me comfortable watching it.

Watching incredibly violent films, or films with extreme depictions of sexuality, requires a level of trust between the audience and the artist, so that we know that what we're watching is not exploitative. Tarantino's milieu has long been walking the fine line between exploitation and empowerment; he creates narratives which are intentionally jarring, designed to unnerve through their extreme use of language and physicality. This isn't to say that Tarantino doesn't employ subtlety when shocking audiences out of complacency. One of his most effectively terrifying scenes is the opening of Inglourious Basterds, in which Christoph Waltz's Nazi commander, Hans Landa, made me sick to my stomach with fear over the course of a multi-minute monologue. Waltz never once rose from his seat; the horror resided completely in the things he said, none of which were inherently awful words, but all of which, when put together, added up to truly fear-inducing discourse.

But far more often, Tarantino utilizes the kinds of words and actions that are guaranteed to garner a different, visceral response from audiences. He's known for the extreme violence in his films, for the unflinching close-ups of bloody beatings, for the way death and dismemberment lurk around every corner. And he's known for liberally using blatantly racist language, most notably the N-word, to an extent that resonates as sharply as any gunshot sound. There have been critical examinations of Tarantino's artistic choices before; there have always been those people asking whether or not his work subverts or supports the controversial subject matter, whether by using racist language and showing torture scenes, he was not tacitly condoning these things, instead of condemning them.

Perhaps never more so was this the case than with the Kill Bill films. The narrative for Kill Bill is a rape revenge fantasy. Watch both movies back-to-back, and you're treating yourself to more than four hours of relentless violence, the majority of which is directed at one woman, The Bride, played by Thurman. Over the course of the film, Thurman is viciously raped and beaten and left for dead more than once. She enacts vengeance upon all those who crossed her, which, of course, leads to even more violence and pain. But the thing that makes watching this film possible, or that made it possible for me to watch anyway, was knowing about Thurman's role in it, knowing that she contributed heavily to every aspect of it. This made the film inherently more interesting to me, then; rather than simply being a man's fetishistic look at how a woman might process trauma, it became a woman's message of vindication, of refusing to define herself as a victim, of instead becoming the victor.

But seeing the film this way was only possible because of knowing that Thurman had consented to this story line. It was only possible not to feel complicit in the violent fantasy of the film because it felt like what we were agreeing to was that the violence was merely a tool used to show a story of female empowerment. Now, all that feels wrong, like the consent audiences gave when watching this film was betrayed, much as it seems the consent Thurman gave to Tarantino when they collaborated on this film was also betrayed.

Thurman told Dowd that her experience on the film was forever changed after she was forced by an angry Tarantino to do her own stunt, and drive an ill-equipped car at 40 miles per hour down a dirt road. Thurman crashed the car, resulting in serious injuries to herself, telling Dowd it was an experience that felt like "dehumanization to the point of death," and that it made her feel like she'd gone "from being a creative contributor and performer to being like a broken tool." Following the crash, when Thurman wanted to see its footage, Tarantino refused, and this betrayal caused, Thurman says, a years-long rift in their relationship.

Thurman said to Dowd that the crash made her feel "disempowered," explaining, "I had really always felt a connection to the greater good in my work with Quentin and most of what I allowed to happen to me and what I participated in was kind of like a horrible mud wrestle with a very angry brother. But at least I had some say, you know?"

But did she? Tarantino's insistence that Thurman do her own dangerous stunt demonstrated how easily dismissed was any control Thurman thought she had on the film. This is all the more troubling when you consider the many other things Thurman did give permission to Tarantino to do to her—including taking over the roles of certain actors, and personally being the one to spit in her face and choke her with a chain, a role he also assumed in Inglourious Basterds, in which he was the one to strangle Diane Kruger's character, Bridget von Hammersmarck—because she trusted him, because they were, in a sense, partners. What the crash demonstrated was that, though she saw their relationship that way, and though she participated in things which she doubtfully would have otherwise were it not for that partnership, Tarantino did not see them as partners. Instead, Thurman was just another "tool" for him in the making of his film, not theirs.

Thurman's relationship with Tarantino has been mended since Kill Bill. But it would be hard for me to watch those films, or any other films by Tarantino, and not feel uneasy, not wonder about what other risks he convinced his actors to take, all the while viewing them as little more than means to an end. And it's an even trickier proposition when knowing Tarantino's own views on consent, which include thinking that a drugged and drunk 13-year-old can adequately consent to sex with a 44-year-old man. All of Tarantino's films feel like one big question of trust for the audience; he is asking us to believe him, asking us to believe that he is not perpetuating narratives of abuse and violence, but rather exhausting these tropes in an effort to extinguish them. Believing that fully has always been complicated. But I also think it's part of the enjoyment, part of why they're so exhilarating; it's because of the lines they cross, the challenges they present. And so while Tarantino has always seemed to take an inordinate amount of enjoyment in the more exploitative aspects of his film, it was possible to believe that watching them didn't make viewers complicit in exploitation, in part thanks to the quality of the actors with whom he worked. Surely if they consented to his vision, it was safe for us, as the audience, to also say yes.

But that consent seems now to have been predicated on a lie—on many lies. Including one which Thurman points out at the end of her Times profile. She told Dowd, "Personally, it has taken me 47 years to stop calling people who are mean to you ‘in love’ with you. It took a long time because I think that as little girls we are conditioned to believe that cruelty and love somehow have a connection." Looking at Tarantino's work and the specific way he inflicts pain on the very characters—and sometimes actors—he most claims to love, makes it possible to question what he thinks is okay to do in the name of that "love." And perhaps in much the same way that we should stop thinking that the boys who pull our hair or push us down on the playground are only doing it because they "like" us, we should also question the artist whose only language is one of anger and violence; the director who has never written a female character who doesn't end up raped or beaten or dead; the writer who settles on only writing female characters who are ciphers, whereas the male characters are fully realized; the photographer who insists its part of his process to have sex with all his models, no matter how unsure they are.

This isn't to say that art can't grapple with issues of exploitation in ways which make audiences uncomfortable. It can and it must. Much of the most exciting and challenging art lives in those liminal and fraught spaces; certainly most of the things to which I respond does. But before we climb up the ladders and look through a magnifying glass and see what is right there, hanging up above us, we should think about what it is we're saying yes to, and if the artist in question is saying YES back to us, or just using our consent as another tool, to manifest their own, noxious vision.