Report On Weinstein’s Secret Settlements Shows How Victims’ Silence Is Bought

“The moment I did it, I really felt it was wrong.”

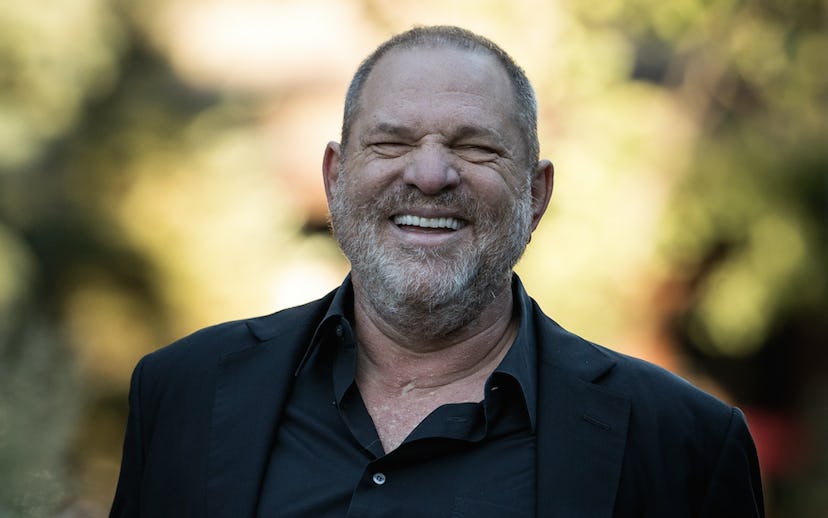

The psychology of how sexual abuse perpetuates in the dark continues to be explored by various writers and researchers. Now, journalists and lawyers are also examining the legal issues behind the processes that allow powerful men to silence their victims. A recent report by Ronan Farrow in The New Yorker delves into the out-of-court settlements that prevented Harvey Weinstein's victims from publicly discussing the abuse they faced.

Bill O'Reilly, Bill Cosby, and Harvey Weinstein have infamously employed out-of-court settlements paired with non-disclosure agreements (which legally prevent victims from speaking out about misconduct) to dismiss claims made against them in public. The prevalence of this arrangement goes beyond the entertainment industry and is even deeply entrenched in our government: the House of Representatives, apparently, has paid more than seventeen million dollars to settle two hundred and sixty claims of harassment over the past twenty years.

“The category of cases where I think we have a problem is the heavy hitters, the rainmakers,” said Samuel Estreicher, a professor of law at New York University. "Repeat offenders are able to operate under a cloak of silence with the help of nondisclosure agreements.”

Weinstein, specifically, finagled his settlements such that they'd often be paid out-of-pocket (sometimes by his brother Bob), making it harder for businesses he interacted with to catch the massive expenditures and question them. Weinstein often preyed upon women who were at a vast economic disadvantage in legal disputes. Some now believe that Weinstein's discreet payments to Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance also helped him avoid official investigations and charges.

“I didn’t even understand almost what I was doing with all those papers,” said Ambra Battilana Gutierrez, a Filipina-Italian model who is a victim of Weinstein's that settled with him in 2015, to The New Yorker. “I was really disoriented. My English was very bad. All of the words in that agreement were super difficult to understand. I guess even now I can’t really comprehend everything... I thought I needed to support my mom and brother and how my life was being destroyed, and I did it. The moment I did it, I really felt it was wrong.”

Gutierrez also says she faced considerable shaming at the hands of press and police who considered the crime. "The only thing I did was exposing something bad that happened to me,” she said. "Just because I am a lingerie model or whatever, I had to be in the wrong. I had people telling me, ‘Maybe it was how you dressed.’"

Weinstein's settlement with Gutierrez mandated the destruction of evidence against him, including audio recordings of him admitting the abuse. Some of Weinstein's victims also potentially face legal ramifications for speaking out now, and many law firms are reluctant to take on these cases.

“I think it’s a really important symbolic thing to do right now,” said Zelda Perkins, a former assistant of Weinstein's who also signed an N.D.A. about the abuse she suffered. “To stand up and question its legitimacy publicly.”

Perkins claims she was disuaded from going to police about what she endured:

[Weinstein's lawyers] just said, "No way. Disney will crush you. Miramax will crush you. They will drag you, your family, your friends, your pets through the mud and show that you are unreliable, insane. Whatever they need to do to silence you." ... I was, like, "Right. O.K. So, we can’t go to police because it’s too late. We can’t go to Disney ’cause they don’t give a shit. So who do we tell? Where’s the grown up? Where’s the law?"

According to the report, Weinstein's N.D.A.s were not limited to cases of sexual harassment. He had also apparently used similar tactics to crush disputes about funds he had been accused of misappropriating from the HIV/AIDS charity, amfAR. Weinstein employees are often bound by far-reaching N.D.A. agreements as well, making it impossible for allies to speak up about their suspicions.

“A forever N.D.A. should not be legal,” said the Weinstein Company’s senior vice-president for accounting, Irwin Reiter. “People should not be made to live with that. He’s created so many victims that have been burdened for so many years, and it’s just not right.”

And yet Weinstein's silencing tactics were all technically legal and so were able to remain somewhat under the radar for decades, raising questions about the ubiquity of these processes. Some efforts are being made to curtail the prevalence of these kinds of agreements; recent reform suggested by progressives would make it possible to track and investigate employers who repeatedly use these types of settlements. To what extent these strategies have been employed by other abusers seems to be an even bigger question, the answer to which is only now revealing itself.