Where Does The Word “Queer” Come From?

We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it.

Recently, my mom was talking with my grandmother about my personal journey and how I have come to identify the way that I do. "My daughter is queer..." my mom started to say, but my grandmother immediately cut her off.

"How dare you say that about my granddaughter," she said. "I love her and will not hear her described in that way."

"Mom. That's the word Jeanna uses to describe herself. That's how she identifies. I love her, too."

"Well," my grandma said, and crossed her arms. "I support her, but I will never call her that word."

To my 88-year-old grandmother, I’m a lesbian; she finds the word “queer” intrinsically offensive. In this, she’s not alone. The word "queer" was, historically, a slur used to describe LGBTQIA+ people, specifically effeminate gay men. It’s only within the last 30 years that there have been serious efforts within the community to reclaim the word for ourselves. Nowadays, the word is represented as the letter “Q” in the LGBTQIA+ acronym and is a word many within the community use to self-identify, myself included. However, the word still incites a knee-jerk reaction among older generations; as the owner of an LGBTQ-focused lingerie business, I’ve received complaints from older customers for using the word in my marketing. But how did the word come to be, and how did we decide to take it back?

To start, what does “queer” mean, anyway? Before queerness was ever associated with homosexuality, it was associated with excess. To be queer was to exceed social boundaries, to be spilling out. It was to be too much, whatever that looked like.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the word “queer” was first recorded as a sexual innuendo on paper in 1508. Over the next few hundred years, the word accrued additional meaning as it was used in literature, in letters, and in often derogatory terminology to connote strangeness, drunkenness, a general over-the-topness. Lillian Faderman reports, “In the 1600s, a ‘queer mort’ was a syphilitic harlot. A 1796 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue lists 23 uses of the word 'queer,' all of them negative... In the 19th century, ‘queer bub’ was bad liquor, a ‘queer chant’ was a false name or address. To ‘shove the queer’ meant to pass counterfeit money.”

So then "queer" not only means excess, but also mistrust, othering, strangeness, coloring outside the lines, and aberrant sociality and sexuality; ultimately, "queer" things that are not trusted by society. So it’s no surprise that the word eventually found its way to same-sex desire.

Snob Queers and SodomyThe first recorded usage of “queer” as a slur toward a gay person was in 1894. John Sholto Douglas, the ninth Marquess of Queensberry in Scotland, had two sons. One son was famously involved with writer Oscar Wilde. However, this story—and, most probably, the Marquess’ raging homophobia—actually begins with his other (also gay) son, Francis, who died under mysterious circumstances. Francis had been the private secretary to Lord Roseberry, and the two had been romantically involved. The Marquess suspected the relationship and, tragically, assumed that Roseberry was somehow involved in Francis’ untimely death. He wrote to his other son, Lord Alfred Douglas, bitterly decrying “Snob Queers like Roseberry.” Little did the Marquess know, of course, that Alfred had been involved with Wilde for years. Years. (The love letters those two wrote each other were on another level.)

When the Marquess did finally discover Alfred’s romantic entanglement with Wilde, he threatened to out Roseberry unless Roseberry prosecuted Wilde for sodomy. At the time, sodomy was a criminal offense, and Roseberry was a public figure, so this was an effective threat. The result was Wilde’s criminal trial for indecency and the famous defense of “the love that dare not speak its name.” The judge passed the most severe sentence the law allowed: Wilde served two years of hard labor in prison, which the judge pronounced as being “totally inadequate for such a case as this.” To be queer was to be criminal. (Fun fact: Sodomy laws weren’t eradicated in the United States until 2003 when the Supreme Court decided Lawrence v. Texas, overriding the remaining 14 states that still had laws outlawing gay sex.)

The word hopped across the pond to the United States in the early 20th century, and puritanical American newspapers immediately picked it up as an adjective for abnormal, unacceptable sexual deviance. By the mid-20th century, “queer” was a common, derogatory slur for a gay person.

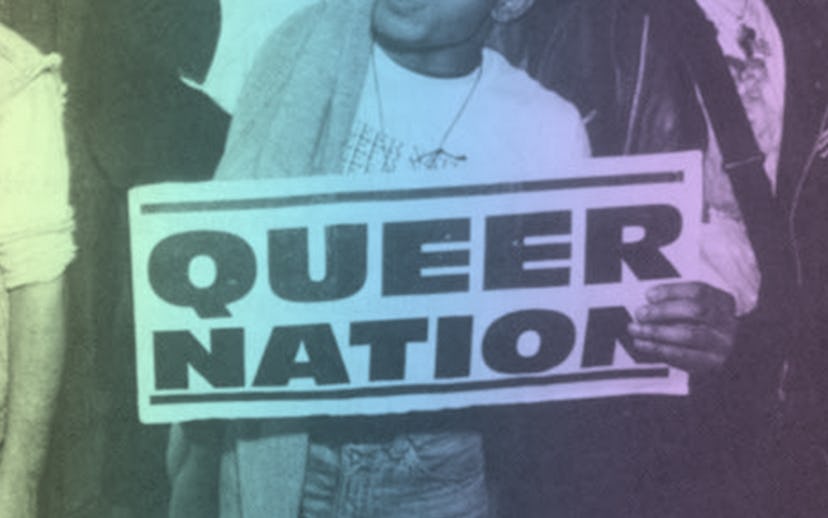

"Queers Read This"Radicalized by the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, corners of the LGBTQIA+ community started to reclaim the word “queer” for themselves, as a form of self-identification. Activists involved in Act Up formed Queer Nation in 1990. As an introduction to their group, they distributed a leaflet entitled “Queers Read This” at New York City Pride in June 1990.

The pamphlet is brutal and honest and raw, laying out in accessible language the ideas that would be articulated in the burgeoning field of “queer theory” soon after. In many ways, “Queers Read This” is a time capsule, capturing the rage and the grief of the early '90s, as queers were watching their friends and chosen family die of AIDS, with no end to the epidemic in sight. But “Queers Read This” still feels timely and relevant, furiously capturing the spirit of queerness—how inclusive and uniting the word is for the community, how it is a "fuck you" to the world that has used it against us, how it is a word of survival.

Queer Nation brought the community together by addressing brothers and sisters together under the umbrella word of “queer”: “How can I convince you, brother, sister that your life is in danger: That everyday you wake up alive, relatively happy, and a functioning human being, you are committing a rebellious act. You as an alive and functioning queer are a revolutionary.” Queer wasn’t a pejorative adjective, it was a noun. You are a queer, and to be queer was to be radical.

The pamphlet also talks about the fact that queer was historically a slur, and the intent behind its reclamation, all in ways that still feel relevant today: “Using 'queer' is a way of reminding us how we are perceived by the rest of the world. It's a way of telling ourselves we don't have to be witty and charming people who keep our lives discreet and marginalized in the straight world… And when spoken to other gays and lesbians it's a way of suggesting we close ranks, and forget (temporarily) our individual differences because we face a more insidious common enemy. Yeah, QUEER can be a rough word but it is also a sly and ironic weapon we can steal from the homophobe's hands and use against him.”

The work of Queer Nation dovetailed with the rising field of queer theory in academia (with breakout stars like Judith Butler), as well as the creation of The New Queer Cinema, a name for independent LGBT-focused filmmaking. “Queer” was rising.

Queer in the New MillenniumIn 1999, Queer as Folk debuted in the U.K. (and in 2000 was introduced in the United States). In 2003, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy followed on Bravo. While these television shows featured predominantly cis white gay men, rather than a diverse array of queer folk of all genders and sexualities that the LGBTQIA+ community had come to associate with the word “queer,” the word’s usage in popular television shows was a major breakthrough on a taboo—and certainly a long way from the Marquess' pejorative letter to his son about “Snob Queers.”

One of the most prominent examples of the cultural shift, particularly in millennial culture, from “gay” to “queer” occurred online, when, in 2016, The Huffington Post’s Gay Voices vertical rebranded to Queer Voices. In the announcement, the editorial team, led by Noah Michelsen, said they’d considered coming out as Queer Voices initially, but were hesitant: “At the time of our launch in 2011 some people felt that the term was too controversial, too divisive and, because of its history as a slur, perhaps just too painful to use.”

But by 2016, times had changed: “We believe that word is the most inclusive and empowering one available to us to speak to and about the community—and because we are inspired by all of the profound possibilities it holds for self-discovery, self-realization and self-affirmation. We also revere its emphasis on intersectionality, which aids in creating, building and sustaining community while striving to bring about the liberation of all marginalized people, queer or not.”

The team at HuffPo emphasized a key element of queerness that appeals to so many who use it: its inclusivity and sense of “profound possibility.” Queerness can apply to gender or sexuality or both; it leaves room for any number of varying and intersecting identities. When Miley Cyrus talks about being pansexual and Ruby Rose talks about the fluidity of her gender, queerness is an umbrella.

Ultimately, this is what is so attractive about the word: Queer leaves the door open for change, for fluidity, while still fully committing a person to an identity outside of the normative.

We’re here. We’re queer. Get used to it.