Entertainment

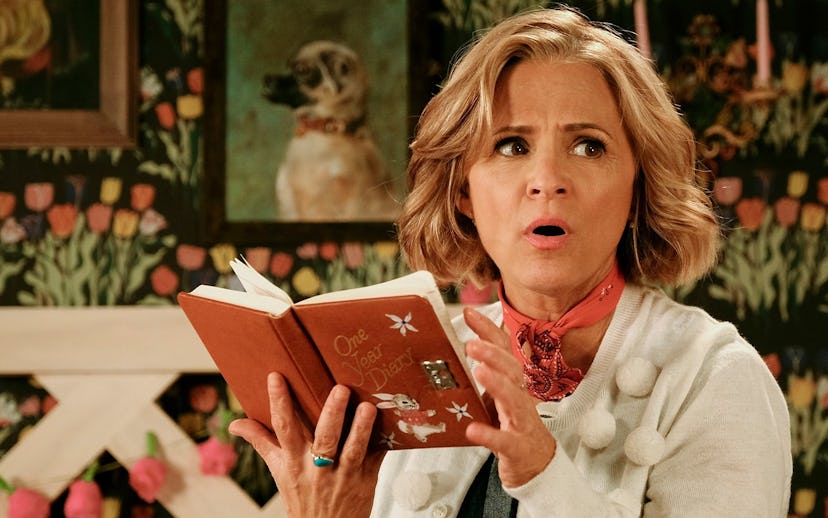

The Cozy, Bizarre Miracle Of 'At Home With Amy Sedaris'

What is it that makes this show so magical?

If Cole Escola wants a drink, he's going to have to sing for it.

Chassie Tucker, one of the actor's many drag alter egos, could really use a cocktail. But hostess-with-the-mostest Amy Sedaris won't let her have it until she's plied the room with a tune. Chassie stands before the assorted guests and warbles out a tremulous rendition of a sad torch song, trying in vain to steady herself as if halfway between fainting and heaving sobs. She gets her drink, and director Paul Dinello has gotten the shot, calling a cut as the scene resets itself to get one last take.

Escola's a sharp, specific performer, but this passage feels particularly studied. Once those script pages are securely in the can and the cast has trod off the sunny, pastel-colored set of At Home With Amy Sedaris (the second season of which premiered last week on truTV)to check their phones, I ask Escola if he had any reference point in mind for his musical number. Without missing a beat, he flatly replies, "Claire Trevor. Key Largo." Though I have never seen the noir classic to which he's referring, I give a chuckle of recognition. I do this in part to save face, because I don't want him to think I don't know things. I also do this in part out of deference—after all, never having seen the movie didn't stop me from stifling my hysterical laughter a few minutes earlier.

In microcosm, this is the miracle of At Home With Amy Sedaris: The show alludes with slavish fidelity to pop culture ephemera its audience has not heard of, and remains one of the funniest programs currently on television anyway. In theory, the brainchild of Sedaris and her longtime collaborator and friend Paul Dinello shouldn't work. It's rooted in the most obscure corners of the most unfashionable parts of the past but succeeds in spite of that (or, perhaps, because of it), by shrinking the distance between now and then. It's fine that the audience didn't spend their childhoods sitting rapt before the oddball local-access programming that mesmerized a young Sedaris. With a little comic distance, she's replicated the experience for modern audiences, ripping open a portal into her cozy, bizarre world.

As a girl in North Carolina, Sedaris was enchanted by domestic fantasies like At Home with Peggy Mann or The Bette Elliott Show, in which impeccably coiffured goddesses of the hearth and home would hold court on the four Fs of food, fashion, fads, and flowers. With modest budgets, these regional broadcasts welcomed viewers into a homey paradise of statement jewelry and creatively used lunch meat. Occasionally, authors, doctors, businesspeople, or distinguished guests from the local university would stop by to share their company and dig into a good meal. Sedaris took this as the model for her metamorphosis into a social butterfly as she aged into adulthood.

"What I always liked about entertaining company is that they can do stuff for me," she says. "If I knew you can build shelves or change a light bulb that's too high, that's great, because I could make you dinner and then you'd help me out. When my brother lived in New York, I entertained a lot. I love the menu-planning, working out the timing to keep what should be cold cold and what should be hot hot. I love working out a guest list, which feels like casting a party."

Her passion for entertaining, her vivid memories of the network channel idylls, and that last point she raises—the occupational overlap between throwing a soiree and running a production—made At Home with Amy Sedaris the perfect vessel for her creative sensibility. Strangers with Candy, her short-lived yet cultishly adored sitcom from the turn of the millennium, repurposed creaky after-school specials for singularly demented humor. Her new show forges a bit further into the 20th century to mimic the aesthetic of the '50s and '70s, when Jell-O molds and other culinary horrors were commonplace. And though the fictionalized "Amy" that Sedaris portrays on the show will make occasional mention of the Research Triangle district of North Carolina, in the truest sense, her home exists outside of time and space.

"We liked the idea of a self-contained universe," Dinello recalls. "There aren't really that many pop culture references. There are no computers, no cell phones. Toronto sometimes feels like aliens visited New York and then tried to recreate it to the best of their memory; we wanted something like that, but with a small town."

The setting could be most accurately described as Planet Amy, a parallel dimension as immersive, kooky, and deceptively personal as Pee-Wee's Playhouse. Sedaris doesn't just star as herself; she also steps in as certified wine lady Ronnie Vino, catty housewife Cindy Snapps, haughty Southern peach Patty Hogg, and Patty's semi-feral daughter, Nutmeg. In conversation, Sedaris can slip into one of these personae in a single breath, squinching her face up to chirp, "Southern hospitality means always havin' an ice cream cake in the freezer, yanawamsayn?"

(Sedaris won't play favorites, but she confesses that Nutmeg and her taped-up nose hold a special place in her heart. "Why doesn't Scotch Tape friggin' call me and have me do a commercial? That's a match made in celebrity endorsement heaven! I love tape, and I'm picky!")

The other faces peopling this insular little neighborhood arrive earthbound and gradually float into a weirdo stratosphere. 30 Rock stalwart Scott Adsit drops in as a Greek restauranteur, and his instruction on the perfect spanakopita takes on gloriously, awkwardly erotic undertones as the sexual tension ramps up. Sedaris refers to repeat guest Michael Shannon as a "softie," though his first appearance segued from a dinner get-together into a dark, disturbing murder mystery. The highlight of the new season comes when Rose Byrne appears as the winner of a fan contest with Single White Female-style ambitions to assume Amy's position.

"I think of the show as Amy sincerely trying to do her show, and exterior situations falling on her while she tries to steer the show back," Dinello explains. "In her mind, she wants to do a simple cooking show, and life misdirects her. In the second season, we wanted to play with the idea of how far we could get from homemaking while still remaining a homemaking show. It's fun to derail the train and let it run into the woods for a while before trying to steer it back to the track."

Show-within-the-show "The Lady Who Lives in the Woods" provides a miniature case in point. Sedaris recreated another pet obsession, a largely lost children's program from '70s Maryland called Hodgepodge Lodge,for the recurring segment featuring nature experts Ruth (Heather Lawless) and Esther (Ana Fabrega). They start out demonstrating a crafting project, all the while quietly sniping at one another in fits of passive aggression betraying a barely-muted lovers' quarrel.

"When I saw [Hodgepodge Lodge], I was like, Oh, my god. It was wonderful," Sedaris says. "Every week, they'd have children come on the show, and they'd look like runaways. Something would seem a little off about the kids, and then you'd never see them again. I loved how slow and boring it was. She was a naturalist, and one day she'd say, 'We're gonna talk about cocoons!' and you'd watch a cocoon do nothing."

With their second season came a bump in resources, and with it, a wider repertoire of eccentric homage. Sedaris and her crew moved on up from a "jewel box-sized" studio in Spanish Harlem to ABC's facilities on the Upper West Side, with enough room to keep several sets up simultaneously. Dinello and Sedaris agree that the shooting schedule for their sophomore run was more ambitious, allowing for experiments like the tone-perfect parody of a kitschy anti-drug PSA videotape Sedaris had been holding on to for years. "Someone sent it to me in, I think, the '80s," she muses. "Just a VHS tape. I wasn't living in New York, and it was all these drug PSAs about the dangers of New York life. I've always wanted to do something with it, and this was my chance." Mimicking the gauzy focus, heinous getups, and wooden line deliveries presented a new challenge for a production adept at placing itself outside the here and now.

That place unstuck from reality is Amy's home, a mishmash of knickknacks approximating the interior of her mind. The set designer used photos of her actual home as the basis for the kitchen and living room sets, reproducing the cheery color scheme and fake fireplace and tastefully placed flowers. She brought a U-Haul of her own possessions to clutter the sets, some of which had been made for photographs in her book, some of which she personally made by hand. "Whenever I heard something break during shooting, my first thought is always, I hope that wasn't mine!" she laughs.

A lamp covered in hair extensions, earrings made of shrimp, a hot dog Christmas tree. Sedaris' set, expanded in its second season to include a walk-in freezer that provides an ice-cold tomb for Amy in one episode and an outdoor area with a tree from which she takes a fall in another, overflows with such bric-a-brac. The house serves as an extension of her personality, formed from an amalgam of idiosyncratic found objects. It allows us to transcend cultural referents we may not share by stepping right into her brain. There, her love for these strange bits of detritus makes sense of them for the uninitiated. That's how she conceived the show—as an invitation to join in.

"People want to go into someone else's world," she reflects. "It's like in I Dream of Genie, when you'd get to see inside her bottle. You felt safe and comfortable and welcomed, because she was there with you. I always brought that up as a reference when I was pitching, though nobody really knew what I was talking about. It was about escapism."