Life

Preparing For A Baby On The Brink Of Apocalypse

What was the appropriate amount of time to torture yourself over something that might never happen?

I wanted to get accidentally pregnant—as much as it could be accidental after having discussed it with my boyfriend, Ian, and stopped our efforts to prevent pregnancy. But, we didn't pay close attention to any of those details so that it would feel accidental when it occurred.

"Wow, I guess this is happening," I'd planned to say. "Not the best timing, but I guess we'll work it out."

*

I've never been good at admitting I want things. Wanting things is stressful, and admitting you want things exposes that stress. You never want to show your feelings to the outside world. It makes you vulnerable to other people's responses, which can run from kindness to ridicule, and every awful thing in between.

It wasn't a great time to have a baby, I had to admit. We had just moved to Spokane and didn't have any friends in town. We had no savings. The coral reefs were dying. Hillary Clinton was debating someone's racist senile grandpa on TV and people were taking both sides seriously.

But then, my plan to accidentally create life didn't immediately work. I got desperate after a few months of "not trying" and downloaded an app that tracked my menstrual cycle and told me what days I was ovulating. I tracked my period but otherwise ignored the app. I didn't want to know what days I was ovulating. That was for planners, and I was still determined to have an accidental pregnancy, like my mother and her mother and all the mothers that came before us. There was a system in place in my family, and, as my family had largely disowned one another, I felt it was important for this one tradition of ours to stay intact. Maybe if I just had a little more insight about my cycle, I could successfully get accidentally pregnant.

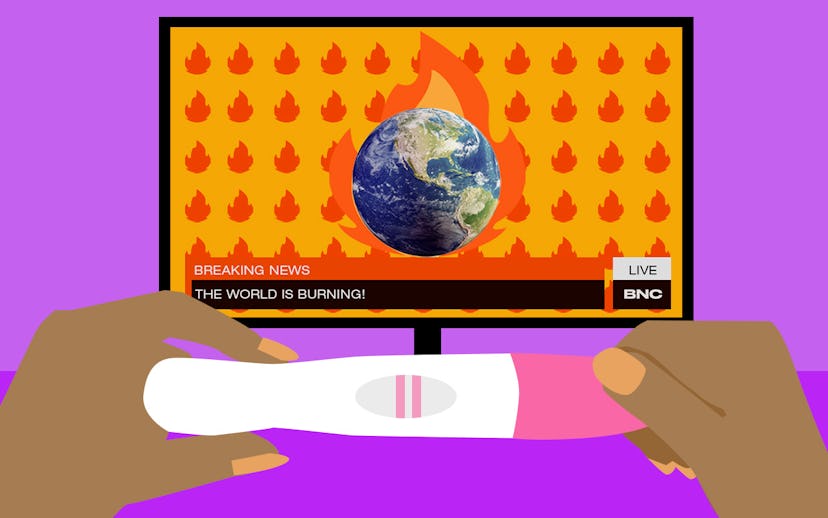

My period was due right after the 2016 election, and when it didn't come, I panicked. The extreme gravity of having a baby at this time in history suddenly hit me. Our world was rapidly turning to an actual tire fire, and instead of fixing it, we had elected an anthropomorphic loogie to govern via Twitter. We were now very firmly on the other side of something, and there was no way to go back. There was no way to unknow the depths of the stupidity of our country, the shocking number of true fucking morons we were dealing with here. There was no way to unsee the way people worship money over the health of our planet and the survival of our species, the utter carelessness for life. There was no way to relax ever again now that the most powerful person in the world was casually invoking nuclear weapons when he didn't get his way.

I was still determined to have an accidental pregnancy, like my mother and her mother and all the mothers that came before us.

Then, a few days later, I got my period. From then on, I had to move forward with the knowledge that any attempt I made to get pregnant, even "accidentally," was a negligent act borne not of hope for the future, but of selfishness and recklessness and willful, dangerous ignorance.

Still, I wanted a baby.

I'm not a great person, I've always said. I'm not evil, I don't think, but not great. This is a preemptive excuse for me not to fully consider the repercussions of my words and actions. I'd rather appear careless or aloof—or even mean—than spend a lot of time worrying about how people will be affected by what I do or don't do. It is an ability of mine to recognize potential problems that my actions might cause and allow that knowledge to slip effortlessly past my consciousness. It was with that natural ability that I began tracking my ovulation, and trying to conceive, in earnest. I timed sex around when my app showed me a big blue asterisk, indicating its best guess for the day an egg would be released from my ovaries. I forged ahead with the plan I made before the beginning of the end of the world. I tried to reconcile my choices with the bleak and terrifying future every smart person on Earth predicted, but I didn't let my lack of progress in coming to terms with reality interfere with trying to make a baby.

*

"What if we never get pregnant?" I said to Ian every month at the onset of my period, terrified at the thought. My synapses were misfiring, it seemed. The dystopia was a far more disturbing and terrible issue than our fertility, but I was only crying about one of them. It seemed there was now no part of me that didn't want to conceive and bring to life a newborn baby that would suffer the consequences of all the previous generations' poor choices. It would be so cute.

Ian got his sperm tested. I got blood work done. We tried to eat less oily foods and processed carbohydrates. I got my period. We tried to drink less. We had sex every other day, timed to land on the blue asterisk. I convinced myself that a line of cystic acne on my neck was a mystical sign of something baby-shaped forming within my body. I got my period. I found statistics online that told me 90 percent of healthy couples conceived within the first year of trying, and counted how many months it had been since our one-year mark. My doctor scheduled me for an ultrasound to make sure my ovaries looked healthy. We had sex every day before the blue asterisk and then stopped. I got my period. We stopped being vegan and started eating eggs again. We went to Buffalo Wild Wings and ordered chicken. We tried to get more exercise. My doctor ordered more blood work. We had sex the day before the blue asterisk and the day after the blue asterisk. I got my period. I looked at adoption websites. I looked at my sad bank account, trying to see it through an adoption agent's eyes. I raged over the fact that one of the details of our hellscape was that it was more economical to create a new person and bring them into the hellscape than it was to adopt a child already living in the hellscape without a family. I got my period. We made a new attempt to drink less. I stopped consuming caffeine. I convinced myself that period cramps were a sign of pregnancy. I got my period. We ignored the blue asterisk and had sex only when we felt like it. I thought maybe the fact that we didn't pay attention to the blue asterisk would work like reverse psychology and trick my egg into mingling with the sperm. My doctor told me there was nothing else she could do and referred me to a fertility specialist, which she told me would not be covered by my insurance. I got my period.

We had officially tried. Had we failed? How long were you supposed to try before accepting failure? What was the appropriate amount of time to torture yourself over something that might never happen? It had been a little over two years. Was this the giving-up point?

Ian suggested getting his sperm tested again.

"Why?" I said.

"I don't know," he said.

We were lonely in the dystopia. It was starting to seem like something was wrong with our reproductive organs. There was no way we could pay for any more tests. Maybe we didn't even want the tests. If there was something wrong with one of us, we wouldn't be able to afford any procedure to fix or get around it. Maybe children were just one more thing poor people should be expected to live without. Maybe, wordlessly, we were giving up.

What was the appropriate amount of time to torture yourself over something that might never happen?

A fun thing Ian and I did to quell our anxiety about the possibility of never having children was to imagine the horrors of the unfolding future.

Our predictions held that every job in the future will be freelance, highly competitive, pay shit, and demand strict worker performance. Not only will you not get paid unless you are actively profiting the company, but companies will sue you if you don't make them enough money. It hurts their bottom line, they will argue, and they will win in court. Interns will pay companies for the pleasure of working for them.

College will exist only for rich people and maybe a few others who have clawed their way there through an impossibly delicate balance of high intelligence, irresistible charm, good luck bordering on magic, and unmistakable, genius-level talent. Everyone else will spend their entire budget on an apartment shared with 10 other people and one piece of equipment with planned obsolescence on which their entire freelance career depends.

Nature documentaries will be tragic records of long-gone history, evidence of all that used to exist, all the possibilities that once were. Millennials will say things like, "I lived at the same time as elephants," and young people will think we're having a senile moment. We'll say, "There used to be bugs that made intricate, mathematical, almost invisible webs, sometimes inside our houses," and it will sound like a fairy tale.

The changing climate will force the world's population into tighter quarters. Illnesses will spread rapidly in these crowded environments. Natural disasters in these areas will be inescapable due to traffic and the fact that there would be nowhere to go. Everyone's favorite people will die.

The remaining population will come together to watch and celebrate as a small private company launches a few Elons into space. There will be a sense of collective hope for the new society being built on some newfound habitable planet, and the promise that the rest of humanity will be joining them in small groups as it is appropriate. It will be branded as a new beginning for humanity, a chance to start over with the wealth of knowledge we'd uncovered by making so many mistakes on Earth. And the people of Earth will kill each other over who will get to be on the first civilian trip to the new planet, not knowing there was never any plan for the Elons to send back for anyone.

*

Right before Christmas, I peed on a stick, and there were two pink lines indicating pregnancy. Ian was on the phone with his boss, so I took a long, unfeeling shower, trying to conjure some kind of emotion from being the only person in the world with this bit of information, but mostly feeling distressed about the temperature of the water, which I could not get right.

Okay, I thought, shivering. And then, Okay.

Ian came into the bathroom as I was drying off, and I showed him the two pink lines. We looked at them together, soberly.

"Wow, really?" he said.

"I don't know," I said. "Are you happy?"

"Yes," he said impassively, staring at the lines.

"Me too."

We hugged briefly, left the pee stick on the bathroom counter, and went back to our workdays.

*

I got sick within two weeks, and regretted my pregnancy almost immediately after that, which did not surprise me. It's very on-brand of me to no longer want something I've wanted for a long time once I've suddenly achieved it.

Pregnancy sickness is terrible, worse than they tell you. I was sick and tired, and that's all I was. Sick and Tired was the entirety of my personality, for weeks, months. I had no sense of humor, no dreams or goals, no will to get out of bed or shower or continue living. I was nauseous to the point of physical pain, had constant headaches, hated the idea of food, and smell became my most dominant sense.

I got sick within two weeks, and regretted my pregnancy almost immediately

What they tell you about a heightened sense of smell during pregnancy does not begin to cover it. What I experienced was nothing short of supernatural. I could smell everything with more clarity than ever before, yes, but I also smelled new things.

I smelled the essence of Ian's humanity, for example. It smelled like a thick, ancient soup mixed with bad breath. I could smell my own human essence as well. The smell of life followed me around like smoke after a campfire. It was nasty, and it couldn't be washed off.

I could smell my headaches. I could smell the fridge being opened through the vent in the upstairs bathroom. I had intrusive unwanted thoughts about ground beef that triggered my gag reflex. If I imagined something being cooked, my brain conjured the smell, and the resulting imaginary smell was sometimes so bad that I threw up.

I forbade Ian from cooking inside our house, and he took to making eggs or quesadillas for himself on a camp stove outside in the snow, which I could still sometimes smell, or thought I could smell, which often made me barf.

The only thing I could bear to eat was anything from Panda Express. It made no sense, I don't even usually like Panda Express, but there was no logical way around it. Panda Express or else, my body told me. But sometimes the or else came either way.

I did everything pregnancy books and the internet told me to do. I ate bottles of Tums and woke up early to take small bites of saltine crackers before getting out of bed. I talked to my doctor about vitamin B6. I napped. I sucked the juice from raw lemons and tried to convince myself that this was all somehow worth the gift of human life.

For 10 weeks, I forgot all about the fears I had for the fetus and focused only on my own problems. It was like the worst vacation, where the weather is bad, all your plans are foiled, everything goes wrong, and you end up missing the shitty boring life you were trying to briefly escape. While I was sick, I thought only about the necessities of survival: What and how much to eat, how to stay awake long enough to work, how to get water from the kitchen without throwing up into the sink. It was a terrible, but simple life. I was not a person, only a body.

In the rare moments when the agony subsided, leaving only a dull discomfort, I had thoughts again. What if all this pain is a metaphor? I thought. What if I am not willing to be physically uncomfortable for the sake of my child?What if being a parent means being more body than person? I didn't want to be a body. I wanted to be my thoughts and feelings, like I'd always known myself to be. I wanted to write and make art and complain to my friends about my other friends. What if I had to give those things up? What if I felt bad all the time forever? What if a child wasn't worth it?

The selfishness of these fears made me feel worried. If physical discomfort was all it took for me to question my interest in motherhood, wasn't that some kind of proof I'd be terrible at the job?

*

At 12 weeks, I got an ultrasound. We saw our fetus, their bones lit up like glow-in-the-dark paint, legs stretched out, arms up. Chill as hell. Half tadpole, half Ferris Bueller. They squirmed around as the technician moved her probe, extended their legs, and shook their head up and down, as if head-banging. I was amazed at how much action was happening inside me without my feeling anything.

I didn't cry, even though I had been very emotional lately. I was silenced by a new feeling, something that I couldn't name. There was somebody precious inside of me, resting in my uterus as if it were a hammock, a boy apparently, who had not yet been faced with anything sad or cruel or hard, and Ian and I would be the ones to introduce him to those things. We would have to give those feelings names, and find ways to explain why he had to feel them, advise him on what to do with those feelings, and give him reasons to enjoy life despite how bad it could sometimes feel. What if we did a bad job?

I was amazed at how much action was happening inside me without my feeling anything.

Then I thought of extreme drought, which is my go-to apocalypse anxiety, and imagined trying to explain to my son, in my limited capacity, climate change, decades of ignorance and negligence that led to wasted precious resources all over the world, and a political system that is not set up to get anything done. I imagined telling him these things at the beginning of a long, impromptu car ride north, where there was rumored to be more plentiful water. I imagined him responding with some passionate kid thing, like, "It isn't fair!" or "Why is everyone so dumb?" and recalling my own long, luxurious showers, my insufficient pleas to congresspeople, and the gray water collection devices I only half-heartedly tried to use. I'd remember my younger self believing that humans would solve our problems before we brought about a literal apocalypse. Humanity had made it this far, after all, and we'd been through some pretty bad stuff. Then again, insects had made it this far, too, and now they were rapidly dying off.

"People are terrible," I'd say to my child, including myself in the generalization.

*

What is scarier to me than the apocalypse itself is the idea that I might not be wrong about it, that my fears might not be the toxic result of my lifelong pessimism butting up against an intensely chaotic political backdrop, that I might, in fact, be delivering the most precious human being I've ever encountered to the unknown horrors of climate change and worldwide economic unrest, and that I might have done this intentionally, selfishly, knowingly, for reasons that don't even make sense to me, such as [idiot voice]: "I want a family."

I realized I had wanted to get pregnant by accident not as an homage to my trashy, birth-control-rejecting lineage, but to remove myself from the responsibility of choosing this world for my child. It was simple cowardice. It was far easier to imagine taking care of a baby who had arrived by mistake into a poor family on a doomed planet than it was to explicitly choose that fate for someone. I was a monster.

The ultrasound technician printed out some images for us to take home, proof our fetus was currently alive and chillin', and Ian pressed them into a sketchbook he had brought with us.

After my ultrasound, we had an appointment with a midwife, who told us we'd have genetic testing choices to make soon. She urged us to decide what we would want to know about our fetus, and whether or not the results of such tests would affect our decision to move forward with the pregnancy. Or perhaps, she suggested, we would just want to know so we had time to mentally or financially prepare. She told us we should also start thinking about our birthing plan, and what we'd want to do if there was an emergency during labor.

At home, I furiously researched these things, as well as stillbirths, SIDS, baby cancer, genetic diseases, learning disabilities, the risks of daycare, internet predators, school shooting statistics, bullying, abduction statistics, and the dangers of YouTube Kids. I relaxed a bit from the sheer abundance of things to worry about, realizing the breadth and depth of things that could go wrong in a lifetime, how powerless I was to prevent anything, and how unprepared Ian and I were for literally any of it. The potential apocalypse hurtling toward humanity was only one of our many problems, just one terrible thing out of many that could hurt or destroy my child.

To assume that the future of our planet will be the most painful aspect of my child's life is to assume that everything else will go right, or that he'll even have the chance to make it to that ominous future. Maybe he won't. But that has been a possibility for every baby that has ever been born.

Our planet has always been fickle. Our people have always been mostly dumb. Terrible things happen every day. And look how far humanity has accidentally gotten.