Entertainment

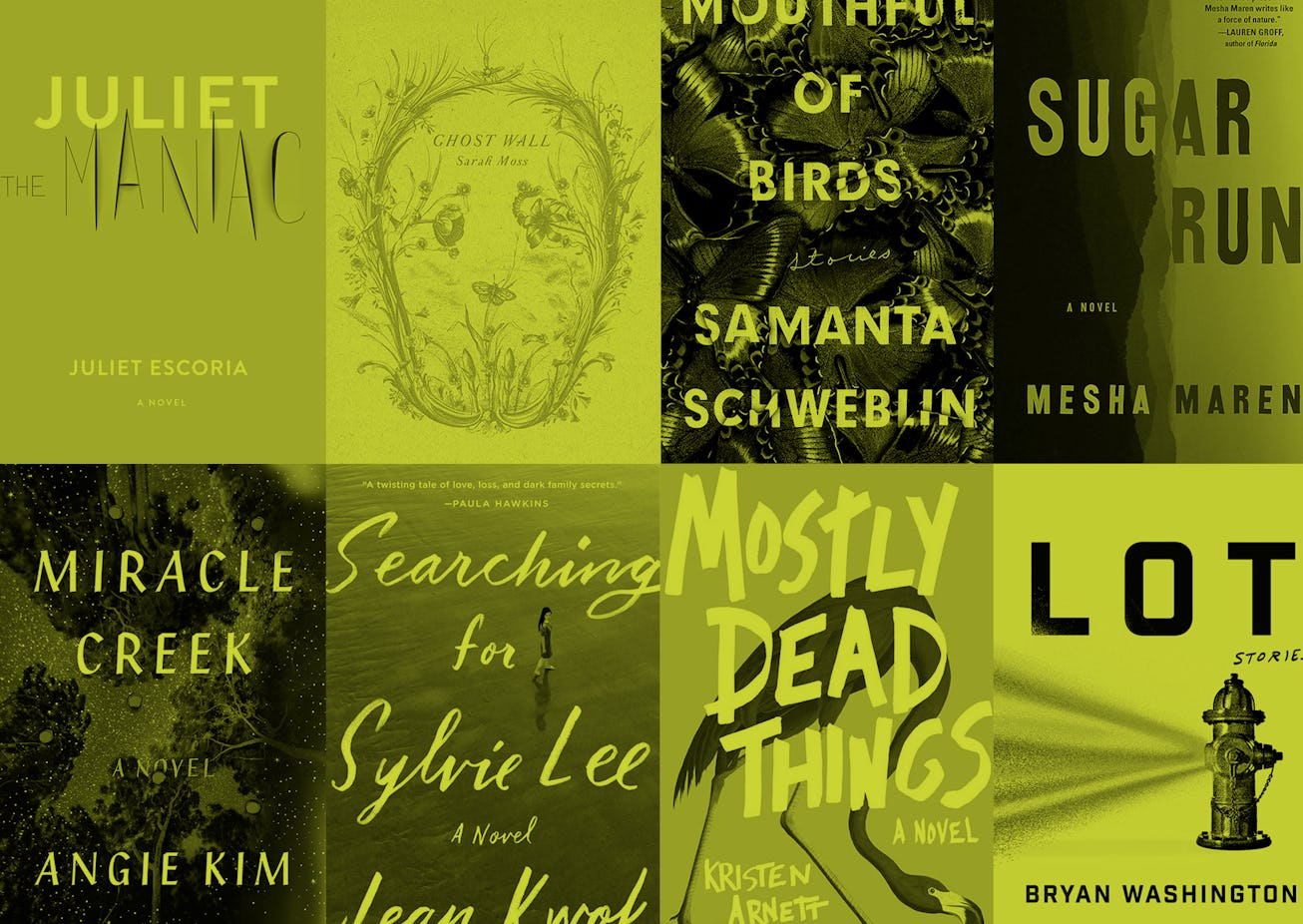

50 Books You'll Want To Read In 2019

At least there'll be good stuff to read

Whatever else you have to say about 2018, there certainly were a lot of good thingsto read. And 2019 offers even more provocative selections for your To Be Read pile. See the list below of the books I'm most excited about for the first half of this year; I know you'll be excited about them too.

Punishment Without Crime: How Our Massive Misdemeanor System Traps the Innocent and Makes America More Unequal by Alexandra Natapoff (available here)

Why not start off 2019 with this sobering account of the manifold ways our country's justice system conspires to further entrench societal inequality by harshly penalizing people for petty crimes, and condemning them to lives that will be forever haunted by the merest brushes with the law? Why not, indeed. Natapoff's account of the way in which the prosecution of misdemeanors perpetuates America's racial and economic divide is a fascinating, heartbreaking look into a side of the penal system that rarely gets the attention it deserves. It's a must-read book for anyone who still has any illusions about who exactly gets a shot at the American Dream.

Sugar Run by Mesha Maren (available January 8)

In her darkly crackling debut novel, Mesha Maren takes readers for a wild ride, the kind that feels like you're hurtling down a backwoods road at night, not quite sure if you're ever going to be able to stop, wondering if you might even suddenly take flight. Maren's story jumps back-and-forth in time, following the lives of two women, both aching with their need for love and freedom. Jodi McCarty has just been released after spending almost 20 years in prison and Miranda Matheson is a single mother, still in her 20s, who has fled an unhappy marriage. The two women find the freedom and love they long for in one another, and embark together on a search for a fresh start in the Appalachian insularity of West Virginia; what they find is a reminder that the past is not just embedded within our present selves, but that is also outside of us, all around, threatening to cover us like kudzu run rampant. Maren details the struggles and triumphs of these women with unflinching precision and language as beautiful and ferocious as a summer storm.

Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss (available January 8)

We live in a time of previously unthinkable technological marvels, and yet people from all parts of the ideological spectrum idealize what they see as a better, more simple past, and do things like eat paleo diets and take DNA tests to feel more connected to their long-ago ancestors. Sarah Moss' slim new novel, Ghost Wall, is a fascinating, horrifying look into the way in which this type of fixation on the past threatens our present and our future. In it, Silvie and her family go on a vacation, in which they embark with a group of grad students and their professor on an excursion to rural Northumberland, where they will live like ancient Britons of the Iron Age. Silvie's father, Bill, longs for those days, when men were men and women were there to serve them. He embraces this experience with a little too much enthusiasm, and Moss skillfully builds an atmosphere of menace and peril, making it so that I both dreaded and couldn't wait to turn every page, simultaneously afraid and compelled by what strange, inevitable violence lay ahead. (Kind of like waking up every day, circa now.) Spend an afternoon reading this marvel of a book, and then spend the next few weeks thinking about nothing else.

Mouthful of Birds by Samanta Schweblin (available January 8)

Samanta Schweblin is a master of the surreal and unsettling, as anyone who read her electrifying novel, Fever Dream, can attest. And now Schweblin is back with this book of short stories, each more unnerving than the last, and all with the unique ability to leave you with that throbbing, pulsing feeling following an electric shock or a sleepless night or a solid scare or all of the above.

A Bound Woman Is a Dangerous Thing: The Incarceration of African American Women from Harriet Tubman to Sandra Bland by DaMaris B. Hill (available January 15)

The prison industrial complex is one of America's most profitable growth industries, and one of the prime examples of how systemic racism works in this country. But while many explorations of the prison system focus on the male experience, DaMaris B. Hill shines a light on the plight of incarcerated black American women, who have been forced into bondage in this country from the time of slavery throughout Reconstruction and up till today. Hill uses the stories of women like Ida B. Wells, Harriet Tubman, Assata Shakur, and Sandra Bland to explore what black women have had to endure in their fight for freedom and respect. It's a difficult, powerful subject, and a history far too few Americans are familiar with; Hill tells these stories with passion and strength, illuminating the ongoing struggle to be free.

You Know You Want This by Kristen Roupenian (available January 15)

It's been just over a year since Kristen Roupenian's short story "Cat Person" (originally published in The New Yorker) about a very bad date went viral—an event which was followed almost immediately by the announcement of Roupenian's debut book of short stories. Readers who are looking for more uncomfortably realistic renderings of awkward romantic encounters won't be disappointed, but this collection is so much more than that, offering an array of biting (sometimes literally!) looks at the ways our most hidden perversions manifest in our lives. It's a razor-sharp, often ruthless, never less than relentless examination of the way we are now. Scary, right? But you know you want it.

Adèle by Leila Slimani (available January 15)

Leila Slimani captivated readers on both sides of the Atlantic last year with her terrifying, brilliant novel about a murderous nanny working for a bourgeois Parisian family, and now American readers can lose themselves in Slimani's Adèle, which similarly exposes the dark desires of a seemingly normal woman. Adèle is a successful journalist with a perfect husband and son, but the ennui she feels with her life can only be vanquished by the thrills she finds in seeking out illicit sex. As her life begins to fall apart because of her lies and compulsions, Adèle—and the reader—must come to terms with what it is we demand of women in modern times, and how those punishing requirements lead so many of us to crack and try and get autonomy through unorthodox means.

Oculus by Sally Wen Mao (available January 15)

This stunning, expansive book of poetry marks Sally Wen Mao as one of the most compelling, provocative poets working today; reading her work feels like being granted access to a new sense, one commensurate with sight, but not limited to those things set before our eyes. The poems range in subject matter from the story of a teenage girl in Shanghai who puts her suicide on social media, to that of Chinese American movie star Anna May Wong, who uses a time machine to travel throughout film history, looking for her legacy and finding a troubling lack of one. Mao's language beautifully encompasses both the natural and technological worlds, infusing both with humanity, and offering a crystal clear vision of the ways in which our culture corrupts and consumes those who don't fit within it seamlessly.

The Current by Tim Johnston (available January 22)

This thriller will both chill you to the bone and have your blood running hot with the excitement of unraveling what exactly is going on in the small Minnesota town where two young women—one dead, and one still barely alive—have been pulled out of an icy river. A similar incident from a decade before is recalled, and the woman who survives searches for answers about both crimes, coming closer and closer to the dark truths that we are often all too happy to leave buried under blankets of white fallen snow.

Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest by Hanif Abdurraqib (available February 1)

With Go Ahead in the Rain, Hanif Abdurraqib does more than just write a biography of seminal hip-hop band A Tribe Called Quest; he not only delivers but transcends his promise to write "a love letter to a group, a sound, and an era." Rather, Abdurraqib explores and exposes the power of music, of art, to not just connect with people, but to connect people, to make movements, to inspire change and revolution, on levels both large and small. In powerful, poetic language, Abdurraqib makes clear the legacy of ATCQ, both the one the group called upon for their own creation and the one they left behind.

Sea Monsters by Chloe Aridjis (available February 5)

There are those points in our life that feel like they're more dream than reality, like if we think about them too hard, they'll vanish from our memories, as if they never really happened. In Sea Monsters, Chloe Aridjis beautifully captures such a time, when the world around us hypnotizes us with its untold potential. Following the journey of 17-year-old Luisa, who impulsively leaves her home in Mexico City on a bus bound for Oaxaca, as she seeks out a troupe of Ukrainian dwarfs from a traveling Soviet circus, Sea Monsters explores questions surrounding young adulthood and enchantment, disillusionment and reinvention, and it's not to be missed.

How to Be Loved by Eva Hagberg Fisher (available February 5)

When Eva Hagberg Fisher was 30, a previously undetected mass ruptured in her brain, sending her down a road of recovery, and also of personal reckoning, as she learned to accept, for the first time in her life, that she was vulnerable, and that she needed the help of other people in order to survive. This moving, beautifully written book reveals the lengths we go to put conditions on our love, the ways in which we resist the people who want to come close to us, and the truth that it is in our weakest moments that we are most likely to find the greatest sources of strength.

Hard to Love by Briallen Hopper (available February 5)

The dominant relationship narrative in our culture is a romantic one: We are taught to prioritize the kind of partnerships that end in marriage—or at least sex—over all others. But, as anyone who has ever had deep, fulfilling platonic friendships knows, there is a lot more to love than just the whole "till death do us part" thing. Briallen Hopper explores the kind of intimacy that doesn't need a registry to be real, those deep and abiding connections that range from sibling bonds to best friendships to less tangible ones, like memberships in fandom communities. Hopper lucidly and compellingly builds a case for these less celebrated partnerships, making this the perfect book to give to a friend and read together.

Black Leopard, Red Wolf by Marlon James (available February 5)

Marlon James is the author of some of the most lush, lyrical, evocative prose of the last couple of decades, and so it's no wonder that his fans have been waiting with bated breath for his first foray into the fantasy world with Black Leopard, Red Wolf. This is the first novel of James's Dark Star trilogy, and it follows Tracker, a mercenary who has been tasked with finding a missing child. Tracker's quest sees him joining up with a group of misfits, including a shapeshifter named Leopard, and takes them all through deep jungles and labyrinthine cities, where they find themselves beset by creatures and obstacles of all kinds. James imbues the story with mythology and magic, and explores the outer limits of truth and power, as he crafts one of the most fully, imaginatively realized fantasy universes ever. Our only question is: When does the next book come out?

The Atlas of Reds and Blues by Devi S. Laskar (available February 5)

"Where are you from?" It's a simple enough question, it would seem, the kind of thing a child would ask guilelessly of someone encountered on the other side of a see-saw. And yet, it's a question that has been weaponized, used to make people feel like they don't belong where they are, like they need to leave and never return. It's a question that sticks like a burr into the consciousness of Mother, an American-born daughter of Bengali immigrants, who refuses to be acquiescent in the face of this country's xenophobia. Laskar has written a searing and powerful novel about the second-generation immigrant experience, making clear the ways in which America terrorizes its own people. It's a violent look at a violent place, and you'll feel forever changed for having read it.

Where Reasons End by Yiyun Li (available February 5)

There is no greater loss than a mother's loss of her child, and it's this irreparable grief that Yiyun Li encapsulates in this heartbreaking, deeply moving new novel, in which a mother talks with her son, Nikolai, about his death from suicide. Li, who has written before about her own suicide attempts, wrote this novel following the death of her own son from suicide, and the profundity of that loss gives a diamond sharp edge to parts of the book, like where the mother says to her son: "I was almost you once and that's why I have allowed myself to make up this world to talk with you." This is a devastating read, but also a tender one, filled with love, complexity, and a desire for understanding.

Bowlaway by Elizabeth McCracken (available February 5)

Maybe it's because I recently watched The Big Lebowski again or maybe it's because I've gone bowling more times this year than any since I was a child, but bowling has been on my mind. And so Elizabeth McCracken's latest novel feels particularly zeitgeist-y for me, but you don't need to be having a bowling moment in order to be fully swept away by McCracken's brilliant wit and keen eye, as she deftly spins an epic, exuberant tale of an eccentric family who runs a candlepin bowling alley in a small New England town. It's a story about family, love, and the murky mysteries that entail when relationships are blurred and secrets kept. It's a pure delight from start to finish, and just the kind of novel to curl up with on a dreary winter's day.

Magical Negro by Morgan Parker (available February 5)

The eagerly awaited follow-up to There Are More Beautiful Things Than Beyoncé, Morgan Parker's latest poetry collection serves as "an archive of black everydayness, a catalog of contemporary folk heroes, an ethnography of ancestral grief, and an inventory of figureheads, idioms, and customs." What you can be sure of is that this archive, this catalog, is told with Parker's signature lyricism and humor; her poems have the ability to soothe and to incite, she nimbly creates spaces for you to rest while reading, and let the power of her words and message sink into you like a heavy stone into water, or a hot knife through butter. It's nothing short of triumphant.

The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang (available February 5)

Although we've come a long way in opening up cultural conversations about mental and chronic illnesses, there are still lots of aspects of mental illness that are stigmatized and deeply misunderstood; among those is schizoaffective disorder, a hybrid condition which is mainly characterized by schizophrenia, but which also includes bipolar disorder and depression. In this insightful, intimate memoir, Esmé Weijun Wang recounts her own experience with schizoaffective disorder and the ways in which she's navigated both living with her illness and living in a world that has long shunned and ostracized those people who display any signs of illness. Wang's clear-eyed look into a complicated reality makes this is an essential read for anyone who better wants to understand why we treat each other—and ourselves—so harshly at any display of weakness; it's a book of compassion and brilliance, an unflinching look at a topic that has long repelled too many of us.

The Book of Delights by Ross Gay (available February 12)

This collection of essays is nothing less than a celebration of being alive, and who doesn't need something like that in their lives? Gay excels at finding and defining the petty pleasures of life, whether the joys of a particular candy or the beauty of flowers growing up out of a sidewalk or pickup basketball games. Each essay, whether a few paragraphs long or many pages, is its own little diamond—far more faceted than it first appears, shining brightly and casting light on everything around it.

American Genius, A Comedy by Lynne Tillman (available February 12)

If you're looking for a book to really just get lost in, this re-release of Lynne Tillman's dense, winding, frantically brilliant novel is a good bet. Notice I didn't say safe bet, because there's little that's safe within these pages. Instead, you'll find the profane, twisted, knife edge-sharp thoughts of a former historian who is meditating on everything from the concept of sensitivity to the Manson murders. And you'll receive these thoughts in the inimitable literary stylings of Tillman, who goes places few other writers can even conceive of existing.

Trump Sky Alpha by Mark Doten (available February 19)

It's an interesting aspect of our current reality that we are all, on some level, aware of the fact that, should an apocalyptic event occur, the last thing many of us will be doing is tweeting: "Wtf did you just see that??" In Mark Doten's subversive, searing indictment of our political era, America is in the midst of a nuclear war, and a journalist has started documenting internet humor in the advent of the apocalypse, hoping to find evidence of what happened to her wife and daughter. Along the way, amidst manifold memes, she uncovers the possible existence of something known as Birdcrash; but what Doten uncovers with this novel is the always pulsating anxieties that fuel our current existence, both online and off, and the ways in which we use irreverence and cynicism as armor against what we know is largely an uncaring world.

The White Book by Han Kang (available February 19)

I could never remember if white is the color of birth or death, but I guessed since it's the color of weddings, it's the color of both birth and death. No matter, because everything I ever thought about the color white has been profoundly altered by reading Han Kang's brilliant exploration of its meaning and the ways in which white shapes her world, from birth to death—including the death of The White Book's narrator's older sister, who died just a few hours after she was born, in her mother's arms. This is an unforgettable meditation on grief and memory, resilience and acceptance, all offered up in Han's luminous, intimate prose.

King of Joy by Richard Chiem (available March 5)

There is an impulse the grieving have—or, at least, there is an impulse I had when I was grieving—which is to seek out more stories of grief. Reading about other people's sorrows is not like getting an instruction manual on how to grieve (that comes naturally), but rather like getting evidence that grief is survivable. Anyway, this is all to say that I've read a lot about grief, but this sentence in Richard Chiem's novel, King of Joy, still knocked me right out with its quiet, piercing truth: "Grief is an out of body thing, the worst secret you can have." This is a book about grief, about trauma and recovery, the ways the world destroys us and the ways we accelerate the destruction of our world. All of it is told in Chiem's inimitable voice; it's unsentimental, hypnotic stuff, you'll race through it, heart beating, eyes burning, recognizing your own secrets on every page.

Long Live the Tribe of Fatherless Girls by T. Kira Madden (available March 5)

Every page of this gorgeous, if harrowing memoir has a moment on it that sticks in you like a blade, carving out a little piece of you; reading it feels like you're examining your own insides. But, of course, the story is uniquely Madden's and recounts her experience coming of age as a queer, biracial young woman in Boca Raton, Florida, a place where cognitive dissonance about the surrounding inequalities and injustices abounds. Madden brilliantly captures the contradictions of a life filled with trauma and beauty, and sensitively dissects the environment of abuse and addiction in which she was raised. Her story is filled with desire and loss, love and forgiveness, and it's an utterly unforgettable debut.

Gingerbread by Helen Oyeyemi (available March 5)

Following the success of Boy, Snow, Bird and What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, acclaimed writer Helen Oyeyemi is back with a family saga that spans generations of women and centers around, well, gingerbread, that spice- and sugar-filled treat that has played a role in much mythological lore. Oyeyemi's novel has the tinge of the folkloric to it: There are family feuds, a childhood friend named Gretel, and many more archetypal touchstones. Tying this all together is Oyeyemi's deft hand, virtuosic lyricism, and graceful ability to find transcendence in all aspects of life, sweet and spicy alike.

Daisy Jones and the Six by Taylor Jenkins Reid (available March 5)

Sex? Check. Drugs? Check. Rock 'n' roll? Check. This is the perfect novel for anyone who invariably chooses "Landslide" when doing karaoke, Taylor Jenkins Reid's latest novel takes place in the wild days and nights of the late-'60s and '70s music scene, as a young woman named Daisy Jones finds herself on the road to making it big. Reid's wit and gift for telling a perfectly paced story make this one of the most enjoyably readable books of the year.

The Municipalists by Seth Fried (available March 19)

It's no coincidence that there's an abundance of novels coming out right now that are set in a not-too-distant dystopian future, but there's only one that centers around the most perfect, odd couple pairing I've encountered recently, and that's Seth Fried's debut novel, The Municipalists. That odd couple comprises an anal, anxious human bureaucrat and a snarky, day-drinking, yet lovable A.I., and the two of them have joined together to save Metropolis—"a gleaming city of tomorrow"—from an impending terrorist threat. If you're a fan of Jane Jacobs, but can't help but hiss and boo whenever Robert Moses' name is mentioned, this is a must-read. Then again, even if you've never spent one day in a city, but are just someone who wants to laugh and marvel at Fried's imagination and wit, this book is also for you. Really, it's for everyone.

Lot by Bryan Washington (available March 19)

This dazzling debut collection of stories is set in Houston, Texas, and allows readers peeks into the lives of myriad city-dwellers, each representing a different, brilliant aspect of this many-faceted city. Washington's stories offer an unflinching look at a part of America that many people don't understand—or care to understand. But Washington's generosity, empathy, lack of sentimentality, vibrancy, and lyricism make it clear that these people, that Houston, is America, in all its messy, complicated, heartbreaking, life-affirming glory.

The Other Americans by Laila Lalami (available March 26)

This powerful, provocative novel centers around the mysterious death of Driss Guerraoui, a Moroccan immigrant who is killed by a car late one night in the California desert town he's made his home. As the details surrounding Guerraoui's death are slowly revealed, more secrets come out about the people he's left behind, the systemic problems within the town itself, and the ways in which America continues to fail the myriad people who call it home.

The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell (available on March 26)

It's hard to believe this is a debut, so assured is its language, so ambitious its reach, and yet The Old Drift is indeed Namwali Serpell's first novel, and it signifies a great new voice in fiction. Feeling at once ancient and futuristic, The Old Drift is a genre-defying riotous work that spins a startling new creation myth for the African nation of Zambia. The book follows the stories of three different families, whose connection to one another hinges on a mere accident of fate, and traces their lives across generations, spanning miles and miles, and as their futures unfold, so too does our understanding of the exigencies of fate as it pertains to myth-making on both a personal and national level. Serpell's voice is lucid and brilliant, and it's one we can't wait to read more of in years to come.

Guestbook: Ghost Stories by Leanne Shapton (available March 26)

In this perfectly uncanny collection of stories, Leanne Shapton explores the many things that follow and haunt us as we go about our lives, unsettling us in sometimes terrifying and sometimes exhilarating ways. Shapton's words are interwoven with images of art and artifacts, adding to the surreal aura of each of the stories, reminding us of the always pulsing energy that imbues nearly everything around us, always, whether we feel it right away or not.

Soft Science by Franny Choi (available April 2)

Inspired by the Turing Test, these beautiful, fractal-like poems are meditations on identity and autonomy and offer consciousness-expanding forays into topics like violence and gender, love and isolation. All demonstrate the ways that our sense of agency allows us to navigate a treacherous world, but still fall prey to it. It's complex territory, but Choi is a gifted, deft guide, steering us through the morass with an unparalleled lyricism and sensitivity.

Prince of Monkeys by Nnamdi Ehirim (available April 2)

This compelling coming-of-age story is an incisive, beautifully written look into modern Nigeria, and offers unsettling insight into the ways in which we are so often at the mercy of powerful forces beyond our control. The debut novel of Nnamdi Ehirim, and inspired by his own life, Prince of Monkeys centers around a young boy, Ihechi, who is torn away from Lagos and his close-knit group of friends following an anti-government riot. As Ihechi adapts to his new reality and navigates his way through the political ruling class, he must come to terms with the sacrifices—including his own innocence—that must be made in order to stay in power. This book vibrates with life, and is a fascinating, necessary read for anyone who has had to grapple with the ways in which the personal is political.

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault: Essays from the Grown-Up Years by Cathy Guisewite (available April 2)

Even before I knew this book was coming out this spring, I'd been feeling for some time like "Cathy" was due for a comeback. Perhaps you, like me, grew up reading the "Cathy" comics in the Sunday paper, following the travails of the chocolate-loving, Ack!-shouting, Irving-dating Cathy, and having an image of her as being the ur-young professional woman in your head, a two-dimensional precursor to Carrie Bradshaw. Not unlike Carrie and company, Cathy's appeal lay in the fact that she spoke openly about the things that women weren't supposed to talk about: anxiety and insecurity and frustrations. She was a touchstone for neurotic girls and women of all ages. And she was the creation of Cathy Guisewite, whose forthcoming essay collection is as full of humor and pathos about life's many mundanities as you'd want it to be. Only this time, there's no comic strips, it's all Guisewite's voice—reliably sane, sparkling, and suffused with the same warmth and wit as we've all come to expect. What a treat.

Women Talking by Miriam Toews (available April 2)

The latest novel by Miriam Toews is based on the kind of true event that almost works better as fiction, so difficult is it to believe that it happened in reality—when Margaret Atwood says that something sounds like it comes from The Handmaid's Tale, you know it's dire. What happened was this: For two years, over 100 women and girls within a small Mennonite community believe that demons have been visiting them and violating them at night as penance for their sins. Eventually, they find out that there were no demons; rather, the men in the community have been drugging and raping them at will. Eight of these women—all of them are illiterate and have had no real contact with the outside world—gather together to make a plan so that they can protect each other and all the women in their community. Their choice ultimately comes down to whether or not they should stay and try and change the only community they've ever known, or flee a corrupt place and enter a world full of strangers and strange customs. It is, in many ways, an impossible proposition, but Toews nimbly navigates this complicated story, laden with relevant political overtones, offering a scathing condemnation of the patriarchy, as well as a sense of hope for a future run by those who won't stay silent about the horrors around them.

Naamah by Sarah Blake (available April 9)

This glorious retelling of the story of Noah's Ark is offered from the perspective of Noah's wife, Naamah, who did not have the same divine calling as her husband, but nevertheless had to go on the perilous journey too, aboard a riotous ship, heaving with wild animals, and venturing into an unknown future. Blake's prose is bewitching, and this narrative is an essential correction to the Bible's male-dominated mythology. Women have always been central to these stories, but it is through storytellers like Blake that they are finally allowed to take their rightful place.

Outside Looking In by T.C. Boyle (available April 9)

T.C. Boyle is a master of fiction that just touches up against reality; past novels have brought to life historical figures like Frank Lloyd Wright, Alfred Kinsey, and John Harvey Kellogg, and Boyle's latest goes into the psychedelic world of Timothy Leary and his 1960s experiments with LSD. Centering around a young couple whose lives seem clearly mapped before them, the novel explores issues of identity and consciousness, reality and invention, and reading it gives the feeling of a total sensory overload—never unpleasant, always bordering on too much, the kind of thing that makes you sit back and smile, look at yourself in the mirror, and think, Whoa.

Miracle Creek by Angie Kim (available April 16)

This stunning debut by Angie Kim is both an utterly engrossing, nail-biter of a courtroom drama and a sensitive, incisive look into the experiences of immigrant families in America. Kim sets her story in rural Virginia, where a Korean-American couple, the Yoos, operate a pressurized oxygen chamber called the Miracle Submarine, an experimental treatment that offers hope for people with little understanding of medical conditions like infertility and autism. After a fatal explosion, the Yoos are placed on trial, and the book becomes a classic whodunit, as secrets are exposed and lies revealed. Kim has written a taut, compelling thriller, but perhaps the most memorable thing about it is the perspective it shares on marginalized communities, who are always one breath away from losing their tenuous hold on their place in society.

Diary of a Murderer by Young-ha Kim, translated by Krys Lee (available April 16)

This is celebrated Korean writer Young-ha Kim's first story collection to be translated into English, and it is filled with the kind of sublime, galvanizing stories that strike like a lightning bolt, searing your nerves. The titular novella follows a reformed serial killer who has given himself one more target—a man who is set to murder his daughter. The stakes of the other stories aren't any lower and involve kidnappings and affairs, trauma and transcendence. It's easy enough to see why Kim has won every Korean literature award and is acclaimed as the best writer of his generation; pick up this book and find out for yourself.

Normal People by Sally Rooney (available April 16)

The much-anticipated follow-up to Conversations with Friends, Sally Rooney's brilliant debut, Normal People is everything you'd want in her next novel: It's filled with characters saying things that sound like things people actually say, and then thinking things they'd never actually talk about out loud, and discussions of class and gender, love and pain, shame and liberation. The novel tells the intertwining stories of Marianne and Connell, two Irish teenagers who grow up in the same provincial town, but come from totally different worlds: She is a brilliant social outcast, who comes from a wealthy family that treats her horrible; he is also brilliant, but athletic and popular, the only child of a single mother, who cleans houses for a living—including that of Marianne's family. Marianne and Connell's foundational relationship is complicated and messy and gloriously real—Rooney perfectly captures the hunger and shame and desire that go along with feeling really seen by someone when you aren't even sure yet what you look like to yourself. The narrative follows Marianne and Connell through to university in Dublin and travels around the world with them as their social circles widen and their lives expand, the thread tying them to one another seems to stretch endlessly, sometimes pulling them back together, sometimes on the verge of breaking. Never does Rooney venture into sentimentality, but rather she uses spare, cogent prose to perfectly get across what it means to be a young person in the world today: "Really she has everything going for her. She has no idea what she's going to do with her life." Read this if you want to be reminded that love stories don't have to have happy endings, or sad endings, or even any endings at all; they exist in an unhinged, open way, there is a beginning, and then there is everything after.

Juliet the Maniac by Juliet Escoria (available May 7)

Every woman who watched any TV show or movie about female friendship is familiar with The Wild One: the reckless, hard-living friends who make life exciting for the main characters. It's Rayanne Graff, not Angela Chase; or Angelina Jolie in Girl, Interrupted, instead of Winona Ryder. The problem is, stories are rarely told from the point of view of the wild ones, even though they are, undoubtedly, the ones who lead more exciting lives. Well, get ready for Juliet, who is that Wild One, the Bad Friend, the girl whose explosive, crackling personality draws people to her and threatens them all with immolation. In this work of autofiction, Juliet Escoria has created a propulsive, addictive story that takes place in 1990s California and centers around teenage Juliet, whose discovery that she has bipolar disorder leads to her entrance into an outpatient mental health facility for teenagers. Once there, she doesn't just treat her mental illness but, instead, figures out a new way to live. This is a coming-of-age story told with a singular honesty; it can feel brutal—it burns—but it's also illuminating, and a necessary counterpoint to all those teenage stories that marginalize the girl we actually want to read about.

Rough Magic: Riding the World's Loneliest Horse Race by Lara Prior-Palmer (available May 7)

When Lara Prior-Palmer was 19, she was reading the internet and discovered the existence of "the world's longest, toughest horse race," the Mongol Derby, "a course that recreates the horse messenger system developed by Genghis Khan." How many of us, at age 19, discovered similarly unknown things and made a mental note of how expansive the world was and then just... kept on reading the internet? Well, we are not Prior-Palmer, who decided to fly to East Asia and sign up for this notoriously challenging race, which many who enter fail to finish. Prior-Palmer didn't just finish—she won, becoming the first woman ever to be Mongol Derby Champion. Her gorgeous, sensual depiction of this race is a literary marvel; it feels like you are riding alongside her across the desolate steppes; her verbal acuity makes vivid the most elusive of landscapes; her triumph becomes ours.

Light from Other Stars by Erika Swyler (available May 7)

Erica Swyler's follow-up to her beloved The Book of Speculation is a masterful story that hops through time to tell a tale of love and ambition, grief and resilience. Centering around Nedda, who starts the novel as a young girl who wants nothing more than to be an astronaut, Light from Other Stars asks readers to question the ways in which we put blinders on when trying to achieve our goals, and takes us on a journey that collapses time and space, offering insight into the ways we connect with one another; it is full of joy and wonder, a reminder to never stop looking up into the stars and the infinite spaces in between them.

Home Remedies by Xuan Juliana Wang (available May 14)

This is the debut story collection of Xuan Juliana Wang and it signals a great, explosive talent. Filled with characters who mirror the chaos and anxiety, exhilaration and despair, desire and fear of the world around them, Home Remedies offers searing portraits of millennial Chinese immigrants, whose myriad lives cannot easily be categorized or understood by the placement of a reductive descriptive label. Wang's shimmering words offer proof that even the most mundane of these lives have the potential to become something extraordinary.

Mostly Dead Things by Kristen Arnett (available June 4)

If you don't follow Kristen Arnett on Twitter, you should probably do so right now; she's a rare bright spot on a soul-deadening site. And if you do follow her, or are otherwise familiar with her writing, you've probably been eagerly anticipating this, her debut novel, and it doesn't disappoint: It is precisely as strange, riotous, searing, and subversive as you'd want it to be. And, yes, its humor is as dark and glinting as the black plastic eye of a taxidermy ferret. But so, the novel centers around the Morton family, whose patriarch has killed himself on one of the tables of the family taxidermy business. Daughter Jessa-Lynn discovers him and soon takes over the business operations, though she's impeded by her mother, who begins to arrange the animals in sexually provocative positions, and brother, who is having a hard time functioning, particularly after his wife—with whom Jessa-Lynn is in love—walks out on him. Got all that? It's chaotic, yes, but it's also a celebration of the strangeness of life and love and loss, all of it as murky as a Florida swamp but beautiful in its wildness.

Patsy by Nicole Dennis-Benn (available June 4)

I adored Nicole Dennis-Benn's radiant debut novel, Here Comes the Sun, and her stunning second novel only serves to solidify her place as one of the finest novelists writing today. Patsy is a story of the ache of motherhood and loss and is a timely example of the sacrifices made by immigrants who come to America seeking all too elusive opportunities. Centering around Patsy, who leaves not only her home in Jamaica, but also her mother and young daughter, after she gets a visa to America, the novel delves into Patsy's disappointments at what she finds in America, but also her relief in being able to explore her sexuality in a way she couldn't do in Jamaica. But also, Dennis-Benn examines the effect Patsy's departure has on her daughter, Tru, who is struggling to make sense of her own sexuality and come to terms with what it means to have been abandoned by her mother. It's a heartbreaking, sensitive book that deftly demonstrates the impossible choices women must make in order to live the lives they want to live.

Searching for Sylvie Lee by Jean Kwok (available June 4)

The titular mystery that launches this stunning novel by Jean Kwok is the disappearance of Sylvie, the eldest daughter of the Lee family, who vanished into thin air after a trip to the Netherlands. It's up to Sylvie's much younger sister, Amy, to make sense of why Sylvie disappeared; in the process, family secrets are revealed and painful truths come to light. Kwok tells this story of an immigrant family with lucidity and compassion, there is sympathy for difficult choices made, but nothing is sentimentalized. Instead, this is a profoundly moving portrayal of the complicated identities that exist even within a single family, and it offers a graceful portrait of the sacrifices we make for love, and the ways in which our choices can't help but forever affect those around us.

On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong (available June 4)

If you haven't yet read Ocean Vuong's Night Sky with Exit Wounds, please do so immediately. And then, because you'll want to read more of his work right away, read "A Letter to My Mother That She Will Never Read," an essay he wrote for The New Yorker that will scrape your insides out clean. And then, well, just be patient till his debut novel, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous, comes out this June, because you'll be used to being eviscerated by Vuong's glistering words by then, and you'll want to feel that searing pain again and again. This novel is told as a letter from an only son to his single mother who cannot read; it speaks to their family history, which begins in Vietnam and continues in America. It is a story of love and identity, transience and trauma, tenderness and rage and survival, and Vuong writes with a clear beauty and insistence unlike any other writer working today.

In West Mills by De'Shawn Charles Winslow (available June 4)

The debut novel of De'Shawn Charles Winslow, In West Mills is remarkable in its ability to create a fully realized world, the kind that feels like you must have visited before, a place where you'd happily spend all your time. The narrative follows Azalea "Knot" Centre, a fan of "cheap moonshine, nineteenth-century literature, and the company of men," (which, I get it, don't you?), who finds herself shunned by much of her community, and so seeks companionships with her neighbor, Otis Lee Loving, who appreciates the project of fixing up Knot's life—not least because he has many problems of his own he hasn't been able to solve. Winslow's writing is full of compassion and wit and generosity; he skillfully weaves together a story of the power of love and friendship, and their ability to redeem even the most troubled souls. This is the kind of book that leaves you smiling, with faith in humanity, and in art's ability to be gracious and redemptive too.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.