Entertainment

15 Great Books To Read This April

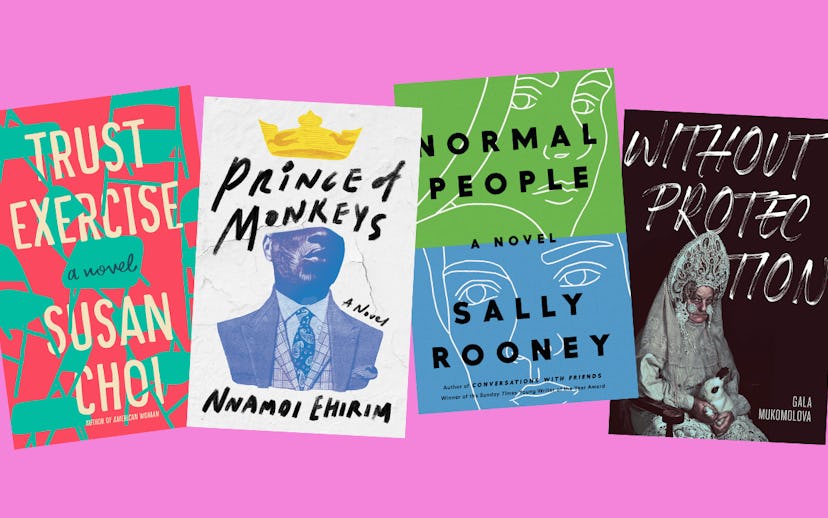

From Sally Rooney to Franny Choi, April's authors are releasing very exciting work

Is April the cruelest month? How could it be when there's so much good stuff to read? Here are 15 books to lose yourself in this spring.

Meander, Spiral, Explode: Design and Pattern in Narrative by Jane Alison (available April 2)

What if everything you know, everything you've been taught, about writing is wrong? Or, if not wrong, precisely, at least restrictive, oriented in only one direction, without much room to get creative and go outside the bounds of what had been done before? This is what Jane Alison explores in her fascinating new book, which looks at the ways in which prescriptive writing has lead to sameness and predictability. Alison encourages an exploration of techniques and styles, offering examples of experimental writing from masters like W.G. Sebald, Clarice Lispector, and Jamaica Kinkaid, as proof of the many ways that writing can shine when not on a typical linear path, when it is allowed instead to spiral and spring forward and back, fold in on itself or unravel in infinite directions, all of which feel new and exciting.

Soft Science by Franny Choi (available April 2)

Inspired by the Turing Test, these beautiful, fractal-like poems are meditations on identity and autonomy and offer consciousness-expanding forays into topics like violence and gender, love and isolation. All demonstrate the ways that our sense of agency allows us to navigate a treacherous world, but still fall prey to it. It's complex territory, but Choi is a gifted, deft guide, steering us through the morass with an unparalleled lyricism and sensitivity.

Prince of Monkeys by Nnamdi Ehirim (available April 2)

This compelling coming-of-age story is an incisive, beautifully written look into modern Nigeria, and offers unsettling insight into the ways in which we are so often at the mercy of powerful forces beyond our control. The debut novel of Nnamdi Ehirim, and inspired by his own life, Prince of Monkeys centers around a young boy, Ihechi, who is torn away from Lagos and his close-knit group of friends following an anti-government riot. As Ihechi adapts to his new reality and navigates his way through the political ruling class, he must come to terms with the sacrifices—including his own innocence—that must be made in order to stay in power. This book vibrates with life, and is a fascinating, necessary read for anyone who has had to grapple with the ways in which the personal is political.

Fifty Things That Aren't My Fault: Essays from the Grown-Up Years by Cathy Guisewite (available April 2)

Even before I knew this book was coming out this spring, I'd been feeling for some time like "Cathy" was due for a comeback. Perhaps you, like me, grew up reading the "Cathy" comics in the Sunday paper, following the travails of the chocolate-loving, Ack!-shouting, Irving-dating Cathy, and having an image of her as being the ur-young professional woman in your head, a two-dimensional precursor to Carrie Bradshaw. Not unlike Carrie and company, Cathy's appeal lay in the fact that she spoke openly about the things that women weren't supposed to talk about: anxiety and insecurity and frustrations. She was a touchstone for neurotic girls and women of all ages. And she was the creation of Cathy Guisewite, whose forthcoming essay collection is as full of humor and pathos about life's many mundanities as you'd want it to be. Only this time, there's no comic strips, it's all Guisewite's voice—reliably sane, sparkling, and suffused with the same warmth and wit as we've all come to expect. What a treat.

Brute by Emily Skaja (available April 2)

Emily Skaja's debut book of poetry is lyrical, visceral, sharp like a fang, and filled with lines that pierce and prod and stay embedded inside your skin. Sometimes, too, it's bitingly funny: "Always a corpse flower, never a bride" had me laughing out loud." In it, Skaja grapples with everything from gender to identity to violence to rebirth, and she inhabits different icons of feminine power to do so, reminding readers of what happens when women interrogate their many sides: They find pain and ecstasy, tenderness and brutality. They find themselves.

Women Talking by Miriam Toews (available April 2)

The latest novel by Miriam Toews is based on the kind of true event that almost works better as fiction, so difficult is it to believe that it happened in reality—when Margaret Atwood says that something sounds like it comes from The Handmaid's Tale, you know it's dire. What happened was this: For two years, over 100 women and girls within a small Mennonite community believe that demons have been visiting them and violating them at night as penance for their sins. Eventually, they find out that there were no demons; rather, the men in the community have been drugging and raping them at will. Eight of these women—all of them are illiterate and have had no real contact with the outside world—gather together to make a plan so that they can protect each other and all the women in their community. Their choice ultimately comes down to whether or not they should stay and try and change the only community they've ever known, or flee a corrupt place and enter a world full of strangers and strange customs. It is, in many ways, an impossible proposition, but Toews nimbly navigates this complicated story, laden with relevant political overtones, offering a scathing condemnation of the patriarchy, as well as a sense of hope for a future run by those who won't stay silent about the horrors around them.

Naamah by Sarah Blake (available April 9)

This glorious retelling of the story of Noah's Ark is offered from the perspective of Noah's wife, Naamah, who did not have the same divine calling as her husband, but nevertheless had to go on the perilous journey too, aboard a riotous ship, heaving with wild animals, and venturing into an unknown future. Blake's prose is bewitching, and this narrative is an essential correction to the Bible's male-dominated mythology. Women have always been central to these stories, but it is through storytellers like Blake that they are finally allowed to take their rightful place.

Outside Looking In by T.C. Boyle (available April 9)

T.C. Boyle is a master of fiction that just touches up against reality; past novels have brought to life historical figures like Frank Lloyd Wright, Alfred Kinsey, and John Harvey Kellogg, and Boyle's latest goes into the psychedelic world of Timothy Leary and his 1960s experiments with LSD. Centering around a young couple whose lives seem clearly mapped before them, the novel explores issues of identity and consciousness, reality and invention, and reading it gives the feeling of a total sensory overload—never unpleasant, always bordering on too much, the kind of thing that makes you sit back and smile, look at yourself in the mirror, and think, Whoa.

Trust Exercise by Susan Choi (available April 9)

The premise of Susan Choi's latest novel is familiar enough: Two students, Sarah and David, are studying drama at an elite performing arts high school. They fall for each other; they fall apart. They fall under the spell of a magnetic teacher; they go on summer vacation and everything changes. But though Choi masterfully tells this type of well-trod scenario, it isn't enough that she makes us reconsider these kinds of relationship dynamics anew; instead, in the second part of Trust Exercise, Choi completely upends the narrative, making readers question everything about what they've trusted to be true, and really ask themselves what truth really means in a world full of people with their own agendas, their own stories to tell.

Optic Nerve by Maria Gainza (available April 9)

Is there anything more exciting than when art defies categorization, resists genre, operates only within the boundaries of its creator's intentions? Maria Gainza's Optic Nerve is one such piece of art; its words shimmer and shimmy inside your head as it leads you to places you've never been, and could only ever have imagined. Part autofiction and part inquiry into the consumption of art, Optic Nerve is a vital read for anyone who knows that seeing something isn't the same thing as perceiving it, and that once you understand the distinction between the two, entirely new worlds can open up, unconstrained from the restrictions too often placed upon them. Writing about art has always struck me as a uniquely difficult task, and it's not that Gainza makes it seem easy, it's more that she makes it seem freeing and shows the beauty and thrills that are possible when you follow your creative obsession.

Without Protection by Gala Mukomolova (available April 9)

If you've ever read Gala Mukomolova's astrological writing, then you already know she's a poet. But did you know she was a poet? Well, now you know. And with your newfound knowledge, you should grab a copy of her ferocious, ecstatic, thrumming collection, which vibrates with a divine feminine energy, an exquisite ache. Without Protection presents a femme duality: the young maiden, Vasilyssa, and the old crone, Baba Yaga, who sit together, in opposition, in tandem, and explore the terrors and wonders of the world. It's a feverish take on a fairy tale, and its ferocity lingers long after you've read the collection's last words.

How to Do Nothing by Jenny Odell (available April 9)

As someone who is on the record as believing that being productive is bad, and that being late is good, I am probably the target audience for Jenny Odell's book, How to Do Nothing. But even if you think you're someone who ~loves the hustle~ and would like nothing more than to figure out how to better optimize your day, I still can't recommend this book strongly enough for the many ways in which it will encourage you to interrogate your relationship to work and free time and the digital age and capitalism. And don't worry, Odell is never didactic in this book, rather she reframes our relationship with the attention economy, expanding how readers see the world, so that they can determine for themselves all the ways in which being constantly connected has led to a loss of connection with ourselves.

Miracle Creek by Angie Kim (available April 16)

This stunning debut by Angie Kim is both an utterly engrossing, nail-biter of a courtroom drama and a sensitive, incisive look into the experiences of immigrant families in America. Kim sets her story in rural Virginia, where a Korean-American couple, the Yoos, operate a pressurized oxygen chamber called the Miracle Submarine, an experimental treatment that offers hope for people with little understanding of medical conditions like infertility and autism. After a fatal explosion, the Yoos are placed on trial, and the book becomes a classic whodunit, as secrets are exposed and lies revealed. Kim has written a taut, compelling thriller, but perhaps the most memorable thing about it is the perspective it shares on marginalized communities, who are always one breath away from losing their tenuous hold on their place in society.

Diary of a Murderer by Young-ha Kim, translated by Krys Lee (available April 16)

This is celebrated Korean writer Young-ha Kim's first story collection to be translated into English, and it is filled with the kind of sublime, galvanizing stories that strike like a lightning bolt, searing your nerves. The titular novella follows a reformed serial killer who has given himself one more target—a man who is set to murder his daughter. The stakes of the other stories aren't any lower and involve kidnappings and affairs, trauma and transcendence. It's easy enough to see why Kim has won every Korean literature award and is acclaimed as the best writer of his generation; pick up this book and find out for yourself.

Normal People by Sally Rooney (available April 16)

The much-anticipated follow-up to Conversations with Friends, Sally Rooney's brilliant debut, Normal People is everything you'd want in her next novel: It's filled with characters saying things that sound like things people actually say, and then thinking things they'd never actually talk about out loud, and discussions of class and gender, love and pain, shame and liberation. The novel tells the intertwining stories of Marianne and Connell, two Irish teenagers who grow up in the same provincial town, but come from totally different worlds: She is a brilliant social outcast, who hails from a wealthy family that treats her horribly; he is also brilliant, but athletic and popular, the only child of a single mother, who cleans houses for a living—including that of Marianne's family. Marianne and Connell's foundational relationship is complicated and messy and gloriously real—Rooney perfectly captures the hunger and shame and desire that go along with feeling really seen by someone when you aren't even sure yet what you look like to yourself. The narrative follows Marianne and Connell through to university in Dublin and travels around the world with them as their social circles widen and their lives expand, the thread tying them to one another seems to stretch endlessly, sometimes pulling them back together, sometimes on the verge of breaking. Never does Rooney venture into sentimentality, but rather she uses spare, cogent prose to perfectly get across what it means to be a young person in the world today: "Really she has everything going for her. She has no idea what she's going to do with her life." Read this if you want to be reminded that love stories don't have to have happy endings, or sad endings, or even any endings at all; they exist in an unhinged, open way, there is a beginning, and then there is everything after.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.