Beauty

How Makeup Became A Weapon For This Fierce Punk Singer

Meet Malaya Harris, who uses beauty to fight body dysmorphia and racism

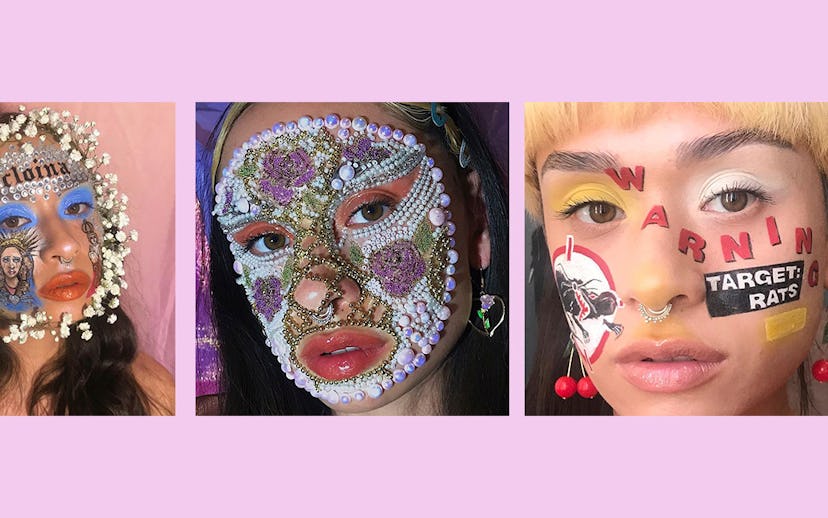

Filipinx punk singer Malaya Harris sometimes pours hours into perfecting a look, whether by applying dozens of tiny jewels to her face or creating elaborate tributes to bands like Discharge or Crass. She blends the latest makeup trends with traditional face-painting techniques, pulling inspiration from everything from classical paintings to punk album covers. The result is a temporary, living art form that moves through the everyday world. But for Harris, it's also a necessary form of therapy and a tool for confronting racism.

As a teen, makeup was the last thing on Harris' mind. "I was very butch," she says, reflecting on early explorations of queerness and finding a queer community. "I wasn't really interested in anything I considered to be feminine."

But when her younger sister began experimenting with makeup, Harris saw an opportunity. She felt insecure about her features: the width of her nose, the shape of her eyes, even her plump lips. In elementary school, she'd spend hours in front of mirrors sucking in her lips to make them seem thinner or pushing her nostrils together to imagine herself with a smaller nose. (Later, her mother would disclose having done similar things as a kid.) Makeup presented a way, as Harris puts it, to "correct" those things—that is, to conform to a white standard of beauty.

However, makeup also created space for her to feel feminine. Growing up, Harris had experienced both physical and sexual violence, and in high school, she struggled with drug and alcohol addiction. Approaching adulthood, Harris got clean. Being tough and channeling male aggression had been as much about survival as exploring gender performance, but now Harris wanted to be soft. What were some ways to get in touch with that part of herself? As much as applying makeup expressed internalized racism, it also gave her permission to "be girlie."

In her early 20s, that all changed. Harris had just escaped a violent domestic relationship. She was scared to leave the house and even more scared to just be seen. Eventually, she was diagnosed with body dysmorphia. Body dysmorphia (BDD) is a mental disorder where a person obsesses over perceived flaws in their appearance to the point where it disrupts their daily life. For Harris, she started engaging in self-harm behaviors and struggling with agoraphobia.

"I would do this thing where I would put on my makeup," she explains. "Then I would feel like a monster, so then I'd wash it off. And then I'd put it on again, and I'd wash it off—over and over and over. It would take me hours to get ready, and then hours more of just sitting on the floor feeling trapped with obsessive thoughts just to try to go out and to see my friends."

At this time, Netflix started streaming the instructional painting show Beauty Is Everywhere, hosted by the late painter Bob Ross.

"[Psychologists] say the body holds onto trauma," she says, "and one of the things that helps with that is developing new—especially sensory—relationships with it… [On his show], Ross talks about creating a world you want and getting a sense of control over your life." She began wondering if using makeup similar to how Ross painted could help her rediscover a sense of agency and allow her to come to terms with her body.

It started with a flower. Harris wasn't going to think about using makeup to create illusions about her "natural" appearance anymore. Instead, she was going to ignore her face altogether and focus on something she liked. Flowers were beautiful and relaxing, and they represented calmness. As a woman of color, she felt like people expected her to have trauma and maybe have an attitude because of it. But that's not what she wanted them to see. That's not what she saw in herself. Harris painted a flower on her face so she could feel confident that she was presenting something worth looking at when she left the house—and that she was being seen for the sensitive, gentle person she is.

From there, she began experimenting with different imagery, moving away from representational pictures altogether and bringing in adornments like sequins and feathers. She even started to match her clothes to her looks; Harris sees her outfits as a way to fuse her love of punk while expressing her heritage and resisting an exotifying white gaze.

As the singer for Chicago punk band Side Action, she'll appear in elaborate makeup and a mixture of athleisure wear, billowing fabrics, bright prints, and studs. Harris sings about things like colonization and her lived experiences of racism, and she'll wear see-through materials as a nod to an ethnographic theory that Spanish colonizers forced Filipinx natives to wear see-through clothing. Supposedly, it was a way to subjugate them and prevent stealing or hiding weapons, so one form of Filipinx passive-resistance was to elaborately ornament their clothes, as though to say, "No matter what you make us wear, we cannot be controlled."

Today, Harris has found a sense of confidence that doesn't require any makeup. She can leave the house with a naked face. Now when she spends hours on her makeup, it feels less like an obligation and more like an opportunity to explore, celebrate, or express something.

"I never want to go back to being that little kid in the mirror pushing my nose together," she says. "I've learned to use art to find a sense of order. It gives me a new appreciation for my face."

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for our wellness newsletter.