Entertainment

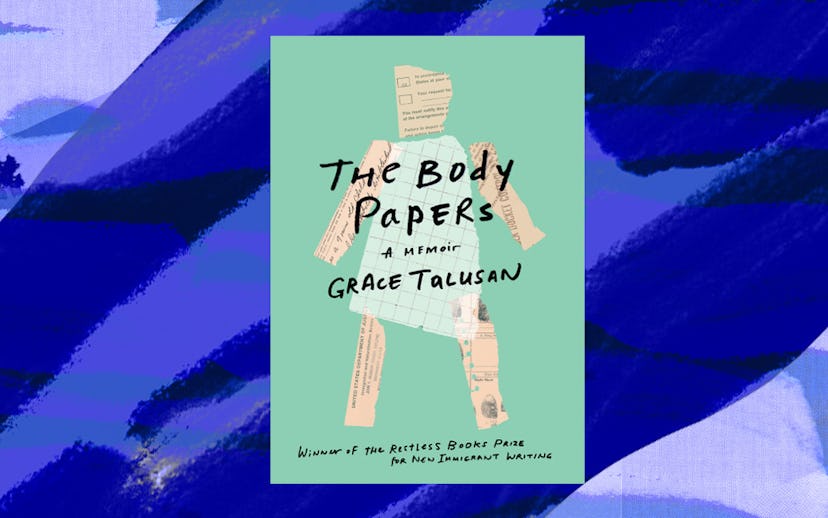

'The Body Papers' Is A Stunning Memoir About Immigration, Family, And Trauma

Grace Talusan is honest and elegant about some of life's most difficult moments

Every single human being alive has a body. Its needs and desires help define and shape our days, its internal workings affect our moods and expressions and energy, and its outward appearance—whether we like it or not—becomes a text to be read by those around us. In The Body Papers, winner of the 2017 Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing,Grace Talusan's new memoir-in-essays, the body is a central theme that the author approaches crablike, edging towards it sideways. Rather than addressing her own sense of embodiment, Talusan examines the body through how it is read by others, how it has been harmed, how it has been cut up and put together. Prize judges Anjali Singh and Ilan Stavan write that Talusan here presents "the concept of 'the body' as a concentric circle that expands outward: the female body, the body of the family, the body of the Philippines, the body of a writer's work." There is good reason for this distancing approach: It mirrors Talusan's relationship to these bodies.

Born in the Philippines to parents of very different socioeconomic backgrounds, Talusan and her older sister were soon uprooted from their home and taken to the U.S., where their father, Totoy, had begun a medical residency program before sending for them and his wife, Norma. Talusan soon lost her first language, Tagalog, as well as many memories of her place of birth. It's her return to Manila, the capital city of the Philippines on the island Luzon, on a six-month Fulbright trip that frames her narrative. But the body of this city is unfamiliar to Talusan, and the bodies that crowd its bustling streets, while more similar to her own en masse than the majority she's lived amongst in the U.S., are foreign to her as well.

This manifests in many ways, but one of the most visceral is the fear that she experiences crossing streets in the city, where traffic is so bad that it takes practice to be a pedestrian. "Physically," Talusan writes, "I don't stand out from the locals, but as soon as I step onto a Manila crosswalk, I distinguish myself by losing my cool: I wave my arms; I raise both hands; I shout, 'Stop!'"

It isn't easy to return to this place that shaped her parents and thus her, but Talusan confronts her own discomfort head-on, acknowledging the complexity of her identity: on the one hand, she is Filipina, raised on her parents' favorite foods like lengua (cow tongue) in tomato sauce, or the dinuguan which she thought was chocolate stew until she learned the soup's rich dark brown was "the color blood turns when it's cooked." On the other hand, she writes, "Every day in Manila, something upsets my expectations, which is a feeble way of saying what I fear makes me ungrateful, ugly, and so American: every day here, I am offended. I am appalled by the rotting inequality, greed, corruption, and lawlessness." And while she is aware that what she sees in Manila exists in the U.S. as well, the fact is that "living in this overcrowded city of 10 million, it's harder to look away from the bodies at my feet."

Between the first few chapters and the final one, Talusan moves, sometimes with an associative quality that renders the individual essays surprising, through themes of immigration, abuse, and illness—all of which are a kind of inheritance, a linking to or severing from the past. She writes about the erasure brought about by assimilation, the loss of her first language, the way she learned to be disgusted by the food she so loved. But Talusan doesn't find fault alone in the American way of living—she is grateful for it, too, for when her mother "learned that you were not supposed to hit small children with slippers and belts and rolled-up magazines, she stopped. She was only repeating what had been done to her." And, more, she is jealous of her nieces and nephews who've gotten to experience her own parents' affection, because she doesn't "remember hugging [her] parents or exchanging 'I love you's with them until later in life."

The importance and comfort that physical affection can provide children is well-documented in various scientific studies, but for Talusan, this isn't a matter of cold facts but rather a facet of her own embodiment, or lack thereof. Instead of safe physical affection from her parents, Talusan spent years experiencing physical harm, in secret. Though Talusan references childhood abuse in the first chapter of the memoir, it takes almost half the book before she shares the details of what occurred to her. Here, too, the structure of The Body Papers mimics the way Talusan relates to the body, for the sexual abuse she suffered remains central to her understanding of self, the trust and self-esteem lost through the years-long ordeal, and the way she has lived more fully in her brain than in her body since then.

In the chapter titled "Monsters," Talusan makes clear that the man who sexually abused her was her grandfather, but despite the chapter title, she takes great lengths to contextualize him for her readers before exposing the brunt of his monstrosity, explaining how he let her burn worms and caterpillars, indulged her desire to set green potatoes on fire and watch them explode, built her a pink bookcase and side table and bed, like the kind she'd coveted in storybooks. But, of course, no amount of grandfatherly attention could make up for the kind that wasn't, and in one stark moment, Talusan breaks her pattern of meaty paragraphs in order to bear witness to her own pain, asking the reader to do the same:

This is what happened and happened and happened.

I was seven and he was seventy.

I was eight and he was seventy-one.

I was nine and he was seventy-two.

I was ten and he was seventy-three.

I was eleven and he was seventy-four.

I was twelve and he was seventy-five.

I was thirteen and he was seventy-six.

There is never a moment of self-indulgence in Talusan's memoir. While she rarely, if ever, judges those around her—even as she notices, and gently notes, their privilege, careless language, or violence—there is the occasional hint of self-recrimination, marking just how difficult it is for her to tell this story. The book examines many more facets of Talusan's life and observations than those I've focused on here, which are only the outermost and innermost sections, and it isn't only her own story, as she writes in her author's note: "While everyone has the right to report their own lives, I know that telling my secrets impacts other people." Yet ultimately, she concludes that she wrote the book for herself, "and for you, the living, and for those who come after [her]." For that, we the living are grateful.

The Body Papers is available for purchase here.

NYLON uses affiliate links and may earn a commission if you purchase something through those links, but every product chosen is selected independently.