Entertainment

This Queer, Feminist Book Defined The Childhoods Of So Many Millennial Women

A look into the power of 'Catherine, Called Birdy,' 25 years after it was first published

"I am commanded to write an account of my days: I am bit by fleas and plagued by family. That is all there is to say."

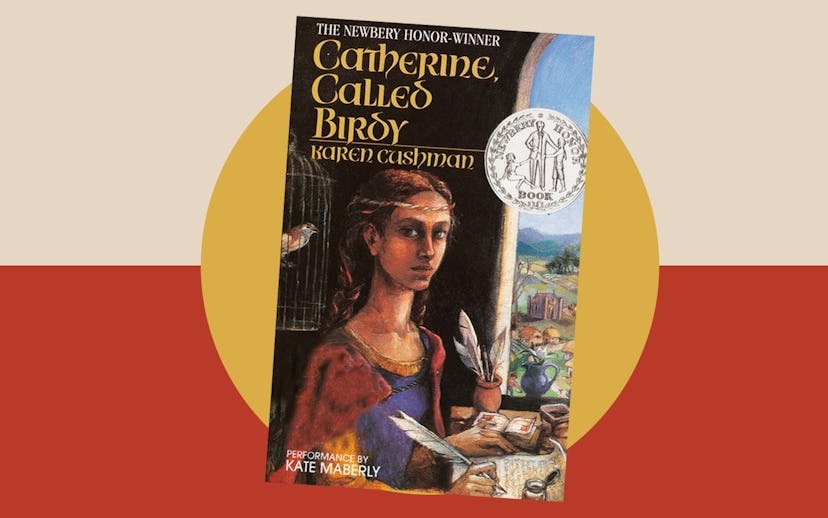

So begins the tale of Catherine, Called Birdy, Karen Cushman's iconic 1994 middle-grade classic. The novel is told in diaristic form by Catherine, a strong-willed heroine in the Middle Ages, whose curses are phrases like Corpus Bones!, and whose primary objective in life is to drive away the suitors her father continually brings to her doorstep. The central conflict of the book is purportedly a marriage plot: namely, the social and familial expectation that Catherine will marry, and her vehement desire not to. There is a constant push-pull between Catherine and her father, himself a sort of bully-ish stand-in for the heterosexist, patriarchal society that was England in the Year of Our Lord 1290.

It's been 25 years since I first read this book. I'm no longer an elementary school student in rural Iowa, beholden to my family's strict Religious Right morality. I'm making a living as a full-time writer in New York City, the kind of life I didn't dare dream of as a child. I got out, escaped from the life that seemed pre-destined for me growing up—something Birdy, too, with all her attempts at running away from home, was obsessed with doing. Sometimes, the stories we love inform our lives more than we realize.

It wasn't just her stubborn feistiness over the marriage plot that made Catherine seem larger-than-life. She was a tomboy who thumbed her nose at ladylike chores, who saw that she didn't quite fit the mold of what a lady should be, and so why bother trying? "My mother gave me a gentle but stern lecture about behaving like a lady," Catherine writes. "Ladies, it seems, seldom have strong feelings and, if they do, never let them show. God's thumbs! I always have strong feelings and they are quite painful until I let them out."

The older women in Catherine's life attempt to shoehorn her into a more socially acceptable path with words; her father attempts to do so with what a modern audience would identify as physical abuse. Catherine writes:

Fought with the beast my father over this joke of a marriage. I roared, he roared, I threw things, he stepped on them, I pushed him, he shouted about stubbornness and pride, which should long ago have been broken, and delivered several hard blows to my face.

The violence is presented as normalized, a product of its time, but the reality is that things haven't changed all that much, have they? Child abuse is rampant and underreported; so, too, is domestic violence. Whether Catherine would consider what is happening to her as abuse is not necessarily the point; there is a diary entry on the first page of the book that includes a report of her father "cracking" her, and the more she fights against him, the worse the abuse gets. "God gave me this big mouth, so I think it can be no sin to use it," she writes, her spirit resilient and persistently unbroken.

In rereading Catherine's story as an adult, it struck me that the plot was driven less by the question of marriage or no marriage and more by Catherine's complicated relationship to socially mandated feminine obedience and submission. Catherine, Called Birdy is about a young girl first forming her selfhood, her identity, trying to find herself against and within seemingly claustrophobic social structures of God and religion and a social class that insists her body is property. Catherine knows she will get in trouble for the simple act of being herself; still, she refuses to bend under pressure.

When I told other writer friends that I was rereading Catherine, Called Birdy, they practically squealed. "I loved that book!" "It was my favorite!" they exclaimed. For a particular age bracket of millennial women, this book was our first feminist guidebook. It was the first fiction that insisted: God wouldn't have given me this if he didn't want me to use it. It said: Your parents don't necessarily know what is best for you. It taught us about consent, showed us that we alone owned our bodies and minds and futures.

Toward the climax of the book, Catherine realizes, in the spirit of The Princess Bride, "What actually makes people married is not the church or the priest but their consent, their 'I will.' And I do not consent. Will never consent. 'I will not.'" It's an extraordinary moment. She is being shoehorned into a version of a woman designed by the era's powerful men, and she realizes that she does not consent. She reminds us that "I will not" are possibly three of the most powerful words a woman can utter, and that we can say them too.

"God gave me this big mouth, so I think it can be no sin to use it"

At this point, it's almost a quaint truism to say, "You can't be what you can't see." But it's true. The reality is that Catherine gives every young person reading her story the words "I will not," and a definition of consent. That is the transformative power that fiction can have in a young person's life.

Of course, the narrative doesn't shy away from the consequences of what a woman's refusal can mean. When Catherine says, vehemently, "I will not," her father beats her—again. She isn't surprised, but she doesn't back down. She is sure of her choice, of her conviction, no matter the cost. And this is the fire in Catherine that so drew me in as a young girl: the consistency of her character and her spirit. I was moved to tears reading it as a child, and I was moved to tears reading it now. I was moved and I was angry because I'm 31 now, carrying enough of my own experiences—and the experiences of women I love—to know that this is how things can happen, and to appreciate the sensitivity and wisdom of a book written for children that provides a roadmap for possible paths ahead.

Catherine's story ends with her departure from her father's home which is, perhaps, the best ending that could be hoped for. The narrative ends with a kind of self-actualization, a realization: that all the running away in the world cannot make you into something else. "I am who I am wherever I am," is a line that repeats throughout the entire book, and finally, Catherine steps into the wholeness of it. The embracing of who she is and where she came from, all the things that have led her to where she is today. There is no shying away from the past, or the things that formed us. But neither does who she is have to change depending on where she goes. She simply is herself, in all her power and all her conviction, no matter her circumstances.

The same is true for the reader, as well: We are who we are wherever we are. But it helps to have books to remind us of that, all along the way.

Want to see more stories like this? Sign up for our wellness newsletter