Entertainment

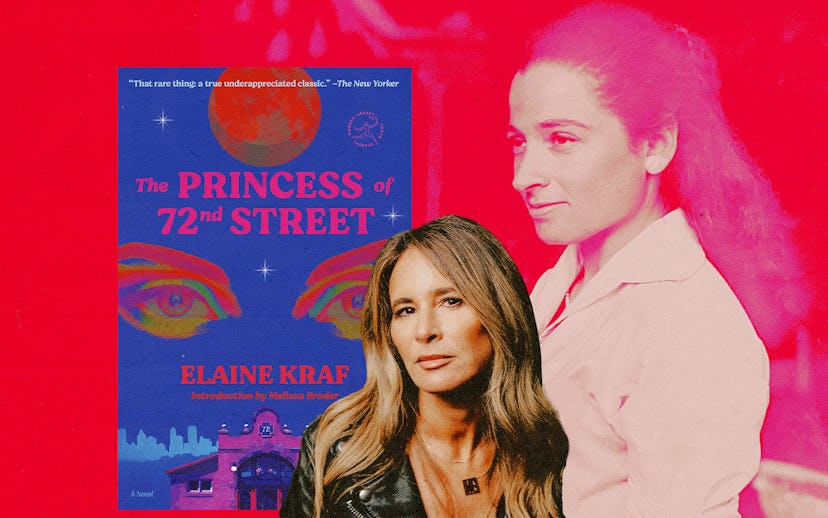

Melissa Broder On The Oddball 1979 Novel Having A Summer Renaissance

“I had never read a manic episode described so beautifully,” says the Death Valley author, who wrote the introduction to a new edition of Elaine Kraf’s The Princess of 72nd Street.

According to my feed, the book of the summer is a tie between Miranda July’s sexy midlife-crisis drama, All Fours; the new Sally Rooney galley; and a slim experimental novel published in 1979. Elaine Kraf’s The Princess of 72nd Street lyrically details the seventh “radiance” experienced by a young figure painter named Ellen who, during fits of seeming psychosis, believes herself to be the sovereign ruler of West 72nd between Broadway and Central Park. Ellen/Princess Esmerelda makes witty observations about creativity, femininity, and public life with a voice that feels startlingly modern: Of Eastside men flirting with her kingdom’s subjects, she says, “We don’t like to be bullied by slick strangers in Gucci jeans.”

Kraf died in 2013, but her fourth and final book lives on — recommended on Twitter by critic Lauren Oyler, snapped on Stories by Substack darling Rayne Fisher-Quann. 45 years since it was first published and two years since writer Hannah Williams dubbed it “a true underappreciated classic” in the New Yorker, The Princess of 72nd Street gets a reissue from Random House, out August 6. It includes an introduction by Melissa Broder, author of Death Valley, Milk Fed, and the iconic millennial-malaise essay collection So Sad Today, born of her Twitter account that catalogs such bangers as “am i an independent woman or just scared of everyone and isolated.” A veritable expert on writing from the perspective of the afflicted woman, Broder tells NYLON why The Princess of 72nd Street should be in the pantheon of mental-illness fiction.

When did you first read The Princess of 72nd Street?

I get asked about blurbing things four or five times a week and probably only blurb four to six books a year. I have this reflexive electric fence up because I need to do my own reading. If I blurb something, I have to love it, and I have to read the whole book. Less often am I asked to write an introduction. As soon as I started [The Princess of 72nd Street], I was like, “Yes, this is a text I want to grapple with.”

What details hooked you? I could not stop thinking about the woman who only wants to paint still-lifes of plums and her husband who has banished plums from their life.

I had never read a manic episode described so beautifully. The book is asking very interesting questions about personal freedom and self-governance, and the line between mental health and spirituality. But as a work of literature on an imagistic level, she’s describing these orange flowers growing from her body and joy cracking out of her every pore, or petal, or cell. There’s self-awareness, but at the same time, you can get lost in the beatific imagery of the experience. I also love the humor and the innate competition that’s going on between men and women, and the particular competition that can come within an artist’s relationship – which is what the plum thing is about.

It’s a story about artists not making art.

Romantic obsession is the same creative energy that we can channel into art. I think that love is an act of creation, too. But it’s very easy, if you have an active imagination, to treat other human beings as a blank canvas and project whatever we want to see onto them. Or to turn that inwards.

Do you experience obsession as a creative block?

When an artist isn’t obsessing about their work, we have a tendency to obsess about ourselves. This book came to me when I had just come out of a period of triple grief. My father had died, I lost an ex to suicide, and then a friend to suicide. I wasn’t really writing that much. I had canceled my Death Valley book tour. I was really obsessing about my own mental health and a lot of my creative energy was going toward trying to fix it. One thing that I identified with in the Princess is, while she is not trying to control her manic visions — she loves her manic visions and her internal experience — she is trying to establish a protocol for how she can live in this state without ending up in the hospital again. She has all kinds of rules for herself and those rules become progressively more elaborate. One might say that some of that obsessing over rules could be put towards her art.

“This woman is shapeshifting. She doesn’t have a stable concept of self – which, like, who does?”

The word “mania” doesn’t actually appear in the book. Do you think of the Princess as “bipolar” or diagnose her with some other modern medical term?

Let's put it this way: She does have manic episodes. And when they end, or if she’s given Thorazine, she does fall into a depression. So we can call that what we may. She describes mania as “full of radiance and flooded with a feeling of small bells ringing and showers of light.” Depression she describes as a pit. There’s a comedown, and the comedown is extremely painful. That is very true to life.

Why does it feel so rare and remarkable among our wellspring of contemporary writing on mental illness to feel like the Princess is a trustworthy narrator?

There are some readers who might say, “How can we trust her?” She’s having visions. She's describing herself as a ballerina, a saint, a mother, a mystic, an ethereal spirit, an Earth goddess. This woman is shapeshifting. She doesn’t have a stable concept of self – which, like, who does? Let’s be real about that fact. What is reliable is that the Princess is committed to telling the truth as she sees it. She’s not hiding anything. We are with her. We are on her side. We are in her head. Even if her view might not be “consensual reality,” her honesty is to be trusted as to her own experience.

Her honesty is what all her boyfriends find so jarring about her within the text. What do you think about the way that Kraf wrote men?

The men don’t come out very well. We’ve got Auriel, the illusionist who she’s madly in love with who then fakes his suicide. We’ve got Peter, the painter who has an emotional allergy to plums because he fears his girlfriend’s success. We’ve got her ex-husband, Adolphe, who is also an egomaniacal artist who has numerous breakdowns when his work involving traffic lights is declared unoriginal. She’s under the thumb of her ex-boyfriend George, who, when she was with him, prohibited laughter and singing and sent her to quite possibly the worst man of all in the book: the psychiatrist, Dr. Clufftrain, who’s totally batshit. He sees patients 21 hours a day and has no boundaries. He’s constantly shaking. He prescribes her weird medicines that make her sick. It’s the blind leading the blind when it comes to the medical profession in this book.

Then there’s the last man…

I wouldn’t say the end is flawed, and I wouldn’t declare it as problematic, because I don't know if there is such a thing as an objective view of art from a subjective place. But I wasn’t keen on the end. Subjectively, I was disappointed. But she has to come back down to Earth. There are sacrifices.

“Romantic obsession is the same creative energy that we can channel into art. Love is an act of creation, too.”

While trying to sell two more novels after The Princess of 72nd Street, unsuccessfully, Kraf wrote to an editor that she “never particularly liked The Princess of 72nd Street as literature.” She described the book as a “farewell to a part of my life composed of dreams and fantasies.” Can you relate to the renouncing of one’s past work?

Many writers — and not just writers, but songwriters and visual artists — look back at their work and have doubts about it. I think it’s a very natural part of the process, especially if you’re in a different place in your life than you were when you wrote it. Once the work is in the world, it can feel like it has taken on a life of its own. Sometimes I’ll read things that I’ve written and I’m like, “I don’t even know who wrote this.” I have no recollection. I guess it’s just the shedding of selves. Artists are the lucky ones who have a record of the layers of self.

What in the book do you think will be particularly resonant for the 23-year-olds reading it this summer?

Self-awareness, reflecting on one’s own interiority in a public way, seems to be something that women are more able to exercise now. With the internet, we’re always reflecting on our interiority in a public way. The romantic obsession in the book, too, that’s eternal, but the Princess has a freedom to take on many lovers that I think is contemporary. I wouldn't say she's polyamorous, but she’s not monogamous. People are interested in non-monogamy.

People are also interested in portrayals of a bygone New York.

I haven’t lived in New York in ten years. The first time I lived in New York was for a summer in 1998, then I was there from 2003 to 2013. But whenever I’m back, one of the areas that feels a little less Chase Bank-ified are parts of the Upper West Side. I mean, it’s all Chase Bank-ified, but around 110th to 116th, Broadway and Riverside, still feels like it has that resonance. There are still diners!

Is it fair to call The Princess of 72nd Street a “cult classic”?

“Cult classic” is a high compliment. Who needs to appeal to everybody? To have written a cult classic, that’s pretty f*cking cool.