Generation K

How K-Pop Is Helping Fans Explore The Full Spectrum Of Gender

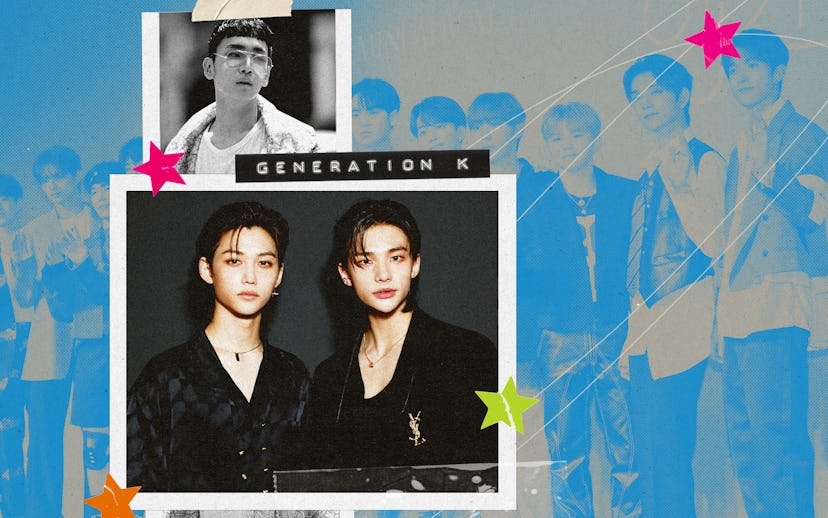

From Stray Kids' Hyunjin to BTS' V, idols are helping queer fans envision themselves outside of the binary.

When Hyunjin from Stray Kids unexpectedly debuted a short, blond chop this October, a certain corner of the Internet mourned the loss of what had become the idol’s signature, medium-length style. In TikTok user @NoeasyCat’s group chat, however, an entirely different conversation was unfolding. “The second that we saw the photos of his haircut, one of my nonbinary friends was like, ‘How is he giving more gender with less hair?’” the 28-year-old content creator tells NYLON.

Hyunjin is one of many K-pop artists who blurs the lines of gender expression, capable of being “both feminine and masculine and powerful and soft and, like, all of the things,” Cat says. “I feel like that’s what a lot of gender-nonconforming fans really relate to and [want to] embody.”

In fandom spaces, gender envy is everywhere. It’s something everyone can experience regardless of your gender identity. A viral Tumblr post defines the phenomenon as “I want your gender,” a phrase you’ll often see across social media platforms. On TikTok, where the tag has accumulated more than 236.8 million views, enby creators share their gender awakenings; scroll through and you’ll find images of fictional characters, anime boys, K-pop stars, androgynous icons, puppets, illustrations of inanimate objects, flowers, and anything or anyone with an aura that they want to emulate. “So many people wanna date Jungkook,” a TikTok from @devepressed reads. “But me? I wanna be him.”

It’s an instinct Cat understands as a fan of Stray Kids. “I don’t feel a strong connection to any sort of gender,” she says, but her TikTok account has become an outlet for own gender expression. “For us AFAB [assigned female at birth] people in particular, there’s no real space to explore femininity outside of the lens of the patriarchy,” she says. “So when we see Hyunjin, for example, expressing femininity and in a really powerful way, and in a way that has nothing to do with patriarchy, or male gaze, or how he’s perceived, it opens up the door for a really safe space to explore that femininity in a way that is inherently masculine and vice versa.”

“When we’re saying that we want their gender, what we’re really saying is that we want to be able to perform and express our gender in the way that they’re performing, however it may be.”

This performance of male femininity is referred to as “liminal masculinity,” a term coined by Chuyun Oh, Ph.D., an associate professor of dance at San Diego State University, and it’s the most common lens through which gender envy manifests online. On TikTok, the phrase “I wish I was feminine the way boys are” has more than 6.1 million views, and hinges on the idea that for men, femininity is a choice and not an expectation.

K-pop, which operates on a more fluid spectrum of gender expression, has become a natural gathering ground for those experiencing gender envy. It doesn’t just challenge Western culture’s more rigid concept of masculinity; it allows its spectators, especially those in the enby and trans communities, to envision themselves outside of the binary. Through idols like Hyunjin, fans can reshape their own gender performance.

“Gender is a social construct, right? And it’s all a performance, and we’re watching these idols perform,” Cat says. “When we’re saying that we want their gender, what we’re really saying is that we want to be able to perform and express our gender in the way that they’re performing, however it may be.”

For Kristen Fournier, a 27-year-old fine arts student from Canada, her journey with gender started with BTS’ V. Growing up, Fournier “never thought of [herself] as being outside of any gender binary,” she says, until an interest in anime and visual kei fashion led to finding K-pop in her teens. Taking cues from her favorite groups at the time, BTS and Exo, she started to explore her own gender expression through outward aesthetics like hair and fashion before coming to the realization that her fascination with K-pop and its beautiful idols went deeper than physical attraction.

Recently, she came across an old Tumblr post of V that she had reblogged while adding the tag “boy self.” At the time, she didn’t have the terminology to describe what she was feeling, but in retrospect, she knows it was some form of gender envy.

“I remember seeing him as being this aesthetic goal,” Fournier says. “I felt like, ‘I want to be this kind of person within my own environment and really push that boundary.’ Me calling V my ‘boy self’ back then is essentially the same as somebody being like, ‘I want to be your gender. I want to be you.’”

It’s the way these idols carry themselves, exude both masculinity and femininity, and aren’t afraid to take up space and demand attention that resonate the most with Fournier. “Physical attributes are what gets your attention to begin with,” she says. “But the more you look, and the more you observe, the more you realize that truly it’s their confidence and their ability to be so authentic that people are drawn to.”

The first time 15-year-old Jupiter remembers thinking “I want your gender” was in 2016. After watching a Shinee music video, he found himself enamored by Key’s magnetic presence. “It’s such a difficult thing to explain,” he says from his bedroom in North Carolina. “It’s the way he expressed himself.”

Jupiter grew up in a sheltered community, where gender wasn’t talked about. “It was either you’re a tomboy or you’re a girl,” he says. “I feel like getting into K-pop and getting more into fandoms definitely opened my view. I never knew there was a world where I could express myself like this.”

Seeing K-pop idols like Key, Seventeen’s The8, and Hyunjin be themselves so freely — wearing shimmery makeup that highlights their more masculine features, growing their hair out, and moving fluidly while still in control of their bodies — empowers Jupiter to see “you don’t just have to stay within social norms.” It also helps him imagine a world in which he, too, can be accepted for who he is. “People are so accepting of K-pop idols who look androgynous,” he says. “I wish I could be accepted like that.”

Through expressing his desire and envy on social media, Jupiter says he’s found a community of people who understands where he’s coming from. “When you say, ‘I wish I could express myself like Hyunjin,’ or ’I wish I could look like that,’ you’ll find a bunch of people who think the same way,” he adds. “It’s validating, in a way.”

“People are so accepting of K-pop idols who look androgynous. I wish I could be accepted like that.”

For idols, experimenting with gender presentation is part of the job. Their onstage looks are carefully cultivated for audience consumption; yet that impacts the way artists like BTS’ Jungkook, who defines great style as “wearing anything you like, regardless of gender,” express themselves offstage, too. G-Dragon, an iconoclast known for his genderless style, told Dazed Korea in 2021: “I like to have fun with clothes and enjoy trying unexpected things. … It’s not just me, but the idea of men and women’s clothing has disappeared.” (An ambassador for Chanel, he’s now exploring his “eccentric grandma” era in cardigans, pearls, and brooches.) Upon the release of his sensual 2017 single “Move,” Shinee’s baby-faced enigma Taemin told Billboard, “My aim was to find a middle ground, mixing both masculine and feminine movements into the choreography together.” Meanwhile, the idols at the forefront of K-pop’s fourth gen are demonstrating their generation’s attitude toward gender-fluid fashion and expression. Tomorrow X Together’s Yeonjun recently told GQ Korea that “men can wear skirts too” in reaction to a 2021 social media post in which he’s wearing a long, black skirt. In an interview with Vogue Korea, he asked, “Who even decided what clothes are for women and what clothes are for men?”

“It comes off as not being afraid of expressing oneself to fans, for idols to start being more like, ‘I happily will wear a skirt,’ or ‘I’ll happily wear makeup,’ outside of the stage makeup that they’re already wearing,” says Aly, a 30-year-old social media marketing professional and longtime K-pop fan in Texas. They point to Harry Styles in a dress on the cover of Vogue, a look that sparked crucial discourse around who gets to be the face of gender-queer fashion in mainstream media, as an example. “They’re not the first one to do it,” Aly says. “But they’re a major male, masculine figure wearing a dress because they want to.”

Though Aly, who’s nonbinary, adds that “it’s never going to be perfect,” the visibility of seeing nontrans, nonqueer men wear more traditionally feminine outfits does help normalize help it for others, especially for trans women. “It’s nice for fans like myself, who are still struggling with who they are,” they say. “Being 30 and seeing idols that are older than me or younger than me especially take control of their identity, it’s really nice to see.”

Gender envy isn’t limited to people either. For 21-year-old trans masculine fan Soryn, songs produced by Stray Kids’ Han Ji-sung play a role in shaping their gender expression. “My gender is a very abstract concept,” the freelance graphic designer says. “When I listen to songs produced by him, I just get this feeling of like, that’s my vibe — that’s what I outwardly want others to see.” It was only after getting into Stray Kids, and specifically Han, that Soryn realized their own gender identity. “Everybody says that they get gender envy from Hyunjin and Felix, but I have gender envy of Jisung,” Soryn says. “He’s not typically who most people think of when they think of the most gender-envy K-pop idols… He’s not the flower boy type with the long hair, but his confidence is so cool.”

As young people, fans and idols alike, continue to explore beyond the gender binary, they’re establishing their own way to talk about gender. The language is ever-evolving, and in fandom spaces, as gender-fluid expression becomes more normalized and accepted, phrases like “that’s so gender” and “give me your gender” become the primary ways in which people can better understand not only their own identities but also the diverse spectrum of gender.

Fournier is more of a casual fan of K-pop these days. She follows some groups but not the whole scene, not like she used to. However, the beautiful boys who once filled her Tumblr dashboard allowed her to imagine herself outside of harmful gender stereotypes. “Who I am as a person now is, in part, thanks to my interest, and temporary obsession, with K-pop.” Idols exude confidence, and it’s their job to make it look effortless. It’s attractive, mesmerizing even, and for trans and enby fans, it can be revelatory.

“It’s right there in the word ‘idol,’” Fournier says. “It’s idolizing. And to idolize somebody doesn’t mean you want to be with them romantically. It’s more like a goal that you want to achieve, in how you look, how you present yourself, what kind of feeling you want to give out to other people.”

Generation K is a column by writer Crystal Bell exploring the trends and issues affecting K-pop and its surrounding community.

This article was originally published on