Entertainment

The Troubling Bitterness At The Heart Of 'Malcolm & Marie'

With his screenplay’s preoccupation with bashing critics, Sam Levinson sullies an otherwise beautifully complicated film about the toxic relationships we inexplicably hold onto.

Warning: Spoilers below for Malcolm & Marie.

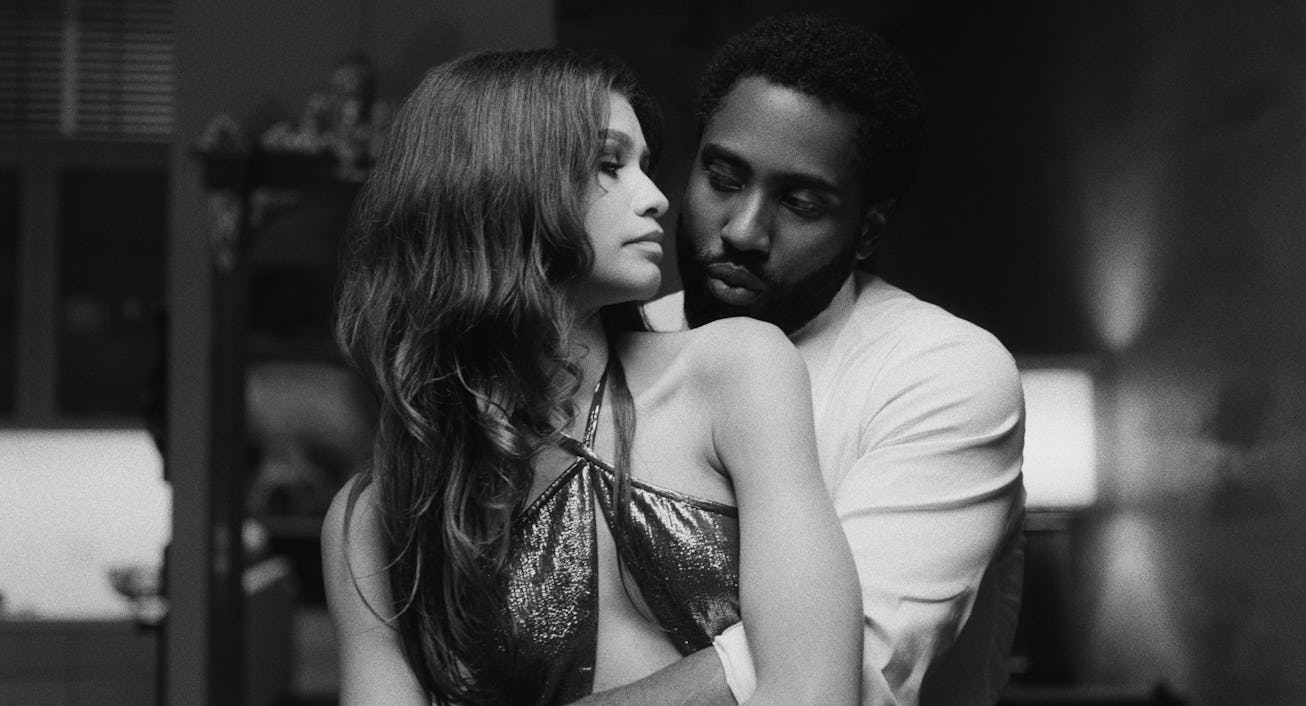

There’s a weird bitterness that runs throughout Malcolm & Marie, and not just because Malcolm (John David Washington), the director whose film-within-a-film just had a splashy premiere when it begins, is as bitter a protagonist as they come. Rather, there’s a bitterness that seems to arise from Malcolm & Marie’s director himself, Sam Levinson, who wrote, produced, casted, directed, and released this Netflix film, all during the COVID-19 lockdown.

In many ways, Malcolm & Marie is an admirable work of art. Levinson’s ability to craft such a fully-realized vision during a time when many were afraid to even open their front door would already be impressive. But the film is also gorgeous to watch, with lush black-and-white cinematography by Euphoria’s go-to Director of Photography Marcell Rév, gorgeous production design by Michael Grasley, and inventive blocking by Levinson himself. For a film sporting an IMDb cast list of two that completely takes place in and around one building (the Caterpillar House in Carmel, California), Malcolm & Marie is surprisingly engaging; it’s dialogue-heavy, sure, but it’s not even the most “this is a play” film gearing up for the 2021 awards season.

Then, there’s Zendaya, fresh off her Emmy win for her lead role as Rue in Euphoria, sinking into an even more demanding role than the one that had her yelling obscenities at her on-screen mother. Marie is remarkably complicated, boiling with the fever that naturally comes from burying one's feelings of pain, shame, and anger for years without release. Acting opposite Washington, who sometimes fails to bring the necessary complexity to a role that requires it (being irate 24/7 is simply not enough), Zendaya shines. It’s impossible to take your eyes off her; when she’s not in immediate frame, you promptly begin wondering when she’ll next appear. Ahead of the film’s release, many people, clearly still prone to envisioning Zendaya as a teenage high-schooler, questioned whether or not the 24-year-old would be believable playing such a decidedly “adult” character. Minutes into the film, Zendaya shuts that notion down.

But the film is not called Marie only. There’s still “Malcolm” to consider, and unfortunately, his character is far less compelling. A pompous director who, on the biggest night of his career, forgets to thank his longtime girlfriend — who may or may not have been the main inspiration for the film now getting him recognition, depending on which character you ask — Malcolm is every bit the unlikable protagonist, and despite the film’s generous 105-minute runtime, there never seems to be any legitimate effort to redeem him.

Of course, not every character needs redeeming qualities, especially if a director wants audiences to solely identify with one character. (Though, here, this doesn’t appear to be the case, with a screenplay that places equal blame on both parties, volleying the upper-hand from one side to another in rapidfire succession.) But there’s a difference between an irredeemable character and an irresponsibly written one — and in Malcolm & Marie, Malcolm is the latter.

See, Malcolm hates critics. From the outset, he seems obsessively preoccupied with them, like he’d prefer they not exist at all. “Afterwards, I talked to, like, six critics. They was all on a nigga,” he excitedly regales to Marie when the pair arrive home from his premiere. He then lists them off: “The white guy from Variety loved it. The white guy from IndieWire loved it. The white woman from the LA Times, she really loved it.” Still, their love is not enough; he just as soon decries the woman for comparing him to Barry Jenkins and Spike Lee instead of William Wyler.

About an hour later, when the first official review is posted, by the aforementioned “white woman from the LA Times,” Malcolm has descended from cloud-nine to the pits of hell. After reading the positive review, which describes him as a “cinematic tour de force,” Malcolm goes on an angry tirade about what he thinks is a slight against his art. It’s understandable that he’d be defensive about claims that he sometimes plays into the male gaze (the reviewer’s only gripe), but Malcolm gets just as worked up over the reviewer’s praise that he successfully “subverts the white savior trope”; in his opinion, he did not (he cast a white person to save the Black protagonist, after all) and was only granted that leeway because he was Black.

The conversation eventually evolves into a larger discussion about the myriad ways critics try to intellectualize films and contextualize filmmakers’ intents — you know, do their jobs. Here, Malcolm raises a few interesting points: when he ponders whether the “male gaze” argument would be complicated by a later revelation that the director was transitioning while filming, I couldn’t help but think back to The Matrix trilogy, which was directed by Lana and Lilly Wachowski before either had publicly identified as trans. (Over two decades after its release, the sisters confirmed that the films were always meant to be a trans allegory.) On the other hand, dismissively asking, “The fact that Barry Jenkins isn’t gay, is that what made Moonlight so fucking universal?” seems to willingly ignore both that Jenkins still shared a kinship with that story — his identity as a Black man, his childhood being raised in those same Florida projects — and that Tarell Alvin McCraney, who wrote the original play and helped adapt the film, is gay.

This general disdain towards critics permeates the film as a whole, but it reaches an uncomfortable fever-pitch in this moment. The dialogue is so painfully specific that it’s impossible not to imagine that it’s coming from a very personal place within Levinson himself.

This element is only further complicated by the fact that Malcolm is also a Black director, and many of his anti-critic arguments are rooted in a self-righteous contempt for white oversimplifications of his vision. (In the film’s earliest moments, he bemoans being pigeonholed as a political director simply because of his skin color.) That Levinson, as a white writer-director, chooses to tackle gripes hyper-specific to Black creatives is one thing. That the film takes such a sick satisfaction in using these gripes to speak out against criticism as a whole is something else entirely.

And still, Levinson somehow makes it hard to argue against him. While watching, I texted a close friend who had also seen the film about the twisted way in which the screenplay seemed to be responding to this very critique in real-time. As Malcolm denounces critics’ tendencies to question a director’s impetus for exploring any particular world, I, too, found myself wondering whether my own discomfort with Levinson’s choice to explore this world was playing right into his hands.

Levinson, of course, has dealt with his fair share of criticism. Though it has since gone on to become a pinnacle of 21st century teen drama, Euphoria was initially met with mixed reviews when its first season premiered all the way back in the summer of 2019. Critics panned its copious drug use and sexuality as gratuitous. Ditto for the director’s breakout feature, 2018’s Assassination Nation, which was met with mixed reviews following its Sundance debut and infamously flopped at the box office, where it barely netted $3 million on a $7 million budget.

What’s odd about the whole thing, though, is that Levinson himself has never seemed like Malcolm. From what I’ve heard from friends, he’s a very compassionate, understanding filmmaker, who habitually consults others when talking about things outside of his purview. In some ways, I can see why he’d want to defend decisions to explore worldviews beyond any given filmmaker’s own — in both Assassination Nation and Euphoria, Levinson, a cis man, put trans women right at the center of the narrative — but his willingness to work with his subjects to help craft their stories has always been public knowledge. (Trans actress Hunter Schafer even got a co-writing credit on the most recent Jules-centric episode of Euphoria.)

So where is this bitterness coming from? Why make your protagonist spend so much time defending himself against non-existent critique?

Late in the film, Malcolm is confronted with his own reality. Though he is a Black man, Marie points out that he was still raised in a comfortably upper-middle class home and eventually went on to receive a prestigious college education. Marie’s frustration stems from her knowledge that her own much more troubled life merely became fodder for her boyfriend’s interest in telling complicated stories he couldn’t possibly conjure up on his own, thanks to his personal privilege. Is it possible that Levinson, the son of Academy Award winner Barry Levinson, is suffering with his own feelings of limited scope? The now-clean director has been frank about his own struggles with drug addiction — no doubt why Euphoria’s Rue and this film’s Marie are both former addicts — but could he still be subconsciously projecting his own insecurities into his work?

“Your lack of curiosity is merely an extension of your narcissism, your megalomania, your egotistical view of the world,” Marie tells Malcolm during one of the film’s many heated moments. Before watching Malcolm & Marie, I never thought that about Levinson, who seemed to exist on the opposite end of the spectrum with his inquisitive willingness to tell stories that extended far beyond his own privileged worldview, in a way that still exhibited an overall sense of care, concern, and well-researched craft. After watching this film, however, I’m second-guessing my initial assessment.

As Malcolm tells Marie during another heated moment, “That is the mystery of art.”

Malcolm & Marie premieres on Netflix Friday, February 5.